Glasgall: "Positive state tax revenues are surprising analysts"

[This article was originally published in The Bond Buyer.]

Positive state tax revenues are surprising analysts

New Jersey and Illinois are the latest states to announce that revenue collections for the current fiscal year are running ahead of earlier estimates. The gains are putting to rest—for now anyhow—speculation that limits on deductions imposed by the 2017 Tax Cut and Jobs Act would negatively impact high-tax, Democratic-leaning states more severely than Republican states with lower levies.

For fiscally stressed states such as New Jersey, Illinois, and Connecticut, the surprise revenue gains are presenting opportunities to close budget gaps that have appeared in fiscal 2019 while also allowing for pension contributions to underfunded retirement systems to be at least maintained at their current rate, if not increased for fiscal 2020. But the increases in revenues are also giving states a chance to continue increasing their deposits of cash into rainy day funds against the day that the second-longest U.S. economic recovery since 1858 comes to an end.

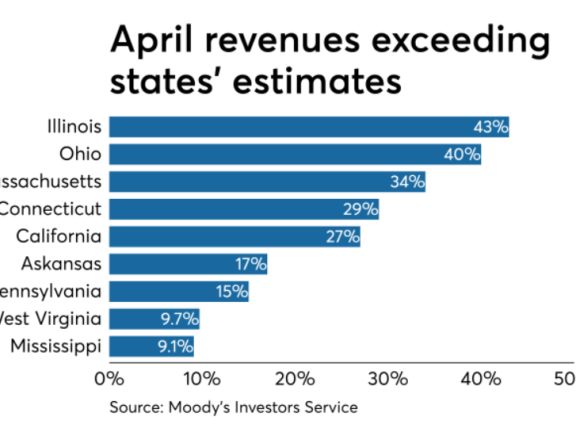

Indeed, at least 10 states are seeing surprisingly strong revenue collections in April (chart), according to Moody’s Investors Service and Volcker Alliance data. The gains are prompting Democratic New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy, for example, to plan on injecting at least $250 million into the Surplus Revenue Fund, the first such deposit in more than 10 years, according to Treasurer Elizabeth Muoio. National Association of State Budget Officers (NASBO) data show that fund has had a zero balance since 2009 after the state drained $734.7 million from the reserve to balance the budget during the Great Recession.

In Illinois, which benefited from a better-than-anticipated 35% rise in personal income tax collections in April, according to Moody’s, Gov. J.B. Pritzker, also a Democrat, proposed depositing $100 million annually into his state’s fiscal reserve if the legislature passes his plan to impose a graduated income tax on state residents. The state currently has just $9.9 million in rainy day funds, an insignificant sum compared with its $35 billion budget.

Rather than being set aside for emergencies, according to the budget document, the rainy day fund was “used as a tool to assist with cash flow until it was nearly drained.” It is little surprise that the Volcker Alliance gave the state a D average grade for fiscal 2016-2018 in Reserve Funds, the second-lowest mark, in our latest report, Truth and Integrity in State Budgeting: Preventing the Next Fiscal Crisis.

The plans in New Jersey and Illinois to fatten rainy day funds put the states in line with others that have chosen to put some of the windfall from the recovery in GDP into reserves instead of current expenditures. Nineteen states received the Volcker Alliance’s top A grade for reserve funds in 2018, compared with 15 the year before, and the uptrend looks likely to continue. NASBO estimates that after falling to only $29 billion in 2010, the year after the Great Recession ended, rainy day fund balances rebounded to $62.4 billion in 2019, close to the highest level in two decades. The median rainy day fund balance, meanwhile, climbed to 7.3%, more than quadruple the 2010 amount. Yet more needs to be done to ensure that rainy day funds remain healthy and available for fiscal natural emergencies.

Along with increasing their reserves, states should put into place strong rules governing rainy day fund withdrawals as well as for making future deposits. We have found that among the 50 states, only Arkansas and Kansas have minimal guidelines for replenishing budgetary reserves. And five states (Illinois, Kansas, Kentucky, Maryland, and Ohio) lack or have limited policies for tapping the funds, according to Volcker Alliance data.

But even in states with clear deposit and withdrawal rules on the books, governors and legislators may choose to override them.

Massachusetts, for example, received an A average Reserve Funds grade for 2016-2018, reflecting robust capital-gains tax receipts in recent years. But in 2017, S&P Global Ratings downgraded the state’s general obligation debt, to AA from AA-plus, for using surplus cash to balance budgets instead of making necessary deposits into the state’s Stabilization Fund.

Rather than setting a one-size-fits all target for rainy day fund balances, states should also tie reserves to the historical volatility of their revenue. This is especially important for states that depend heavily on capital gains levies or severance taxes from oil and natural gas production.

Yet 31 states fall short in this regard.

Capital gains-dependent New Jersey, and New York, for example, lack a formal link between revenue volatility and reserves (in contrast to Connecticut, California and Massachusetts). Many energy-producing states are more attuned to swings in revenue and adjust reserve targets accordingly (think Alaska or Texas). Yet some, such as Colorado and Wyoming, still do not.

For the most part, states are taking to heart the need to save when the economy is flush. But regulating how states build and spend their rainy day funds can be as important as whether they are putting money aside.

In good times and bad, fiscal reserves should always be managed with a goal of achieving long-term budget stability instead of one-time fixes that may not be sustainable.

William Glasgall is senior vice president and director of state and local programs at the Volcker Alliance, a nonpartisan, nonprofit organization.