The True Size of Government

Tracking Washington’s Blended Workforce, 1984–2015

America has relied on a mix of federal, contract, and grant employees to faithfully execute the laws since its first breath of independence in 1776. The number and mix of employees have changed over time, but Washington’s blended workforce is still hard at work creating a more perfect union and securing the blessings of liberty that the preamble to the US Constitution promised more than two centuries ago.

Although Washington’s blended workforce has an imperative role in the nation’s success, it may have grown so large and poorly sorted that it has become a threat to the very liberty it protects. With seven to nine million employees, the federal government’s blended workforce may have become too complicated and codependent to control. Most importantly, it may have become so complex that Congress and the president simply cannot know whether this blended workforce puts the right employees in the right place at the right price with the highest performance and fullest accountability.

Tracking Washington’s Blended Workforce

This paper provides an update of my past headcounts of the true size of the federal government’s blended workforce in the context of Dwight D. Eisenhower’s 1961 farewell speech. Eisenhower not only added the term military-industrial complex to the national vocabulary in this address but also warned of the “potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power” in “every city, every statehouse, every office of the federal government.”

Eisenhower believed the military-industrial complex was a necessary weapon against a “hostile ideology global in scope, atheistic in character, ruthless in purpose, and insidious in method.” He also understood that the complex was inevitable in an era of rising nuclear tensions. “We recognize the imperative need for this development,” he said. “Yet we must not fail to comprehend its grave implications. Our toil, resources, and livelihood are all involved. So is the very structure of our society.”

Eisenhower might make the same argument about today’s blended workforce of federal, contract, and grant employees. He might describe the true size of the domestic, nondefense workforce as just as “large,” “immense,” and “vast” as that of the military-industrial complex he described in 1951. He might even ask why his successors have often promised to cut the federal government down to size during their campaigns but have rarely mentioned the contract and grant workforce as part of the total. President Donald Trump ignored the true size of the blended workforce during the 2016 campaign when he promised to freeze federal hiring as part of an attack on the “corruption and special interest collusion in Washington.” He promised to cut the price of the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter and to cancel the order for a new Air Force One if the price did not come down, but he never mentioned the contract or grant workforce as part of his pledge to “drain the swamp” in Washington.

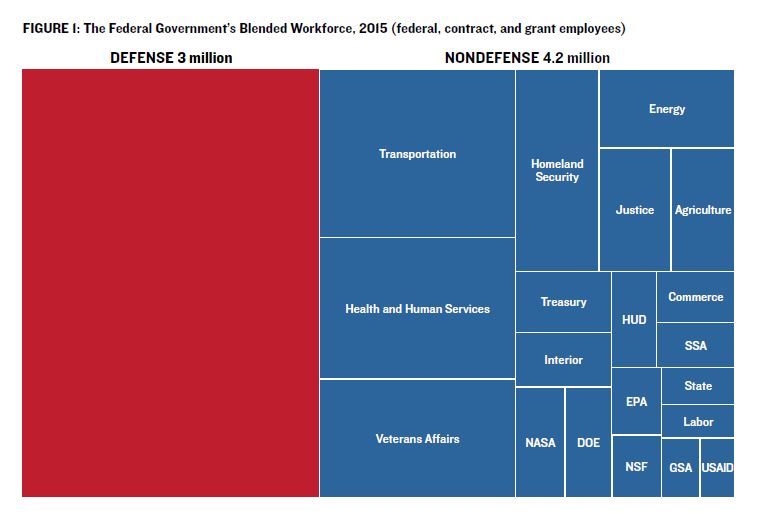

However, as Figure 1 shows, more than seven million employees worked for the federal government when Trump announced his campaign for the presidency in 2015. The Defense Department still relied on the largest number of federal, contract, and grant employees of any single department, but the nondefense departments and agencies had the larger number of employees blended together. Some of these agencies must have had fewer contract and grant employees during the 1950s—after all, the departments of Energy, Homeland Security, Housing and Urban Development, and Transportation had not been created yet; the Education Department had not been carved off Health, Education, and Welfare; and the Veterans Administration had not been raised to cabinet status. Readers should note that Figure 1 excludes active-duty military personnel and US Postal Service employees, which together would add

two million employees to the accounting.

The True Size of Government

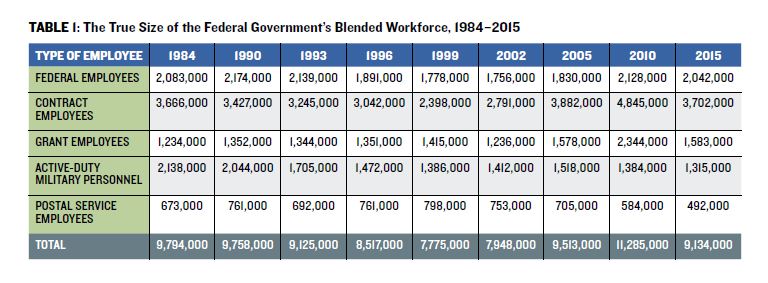

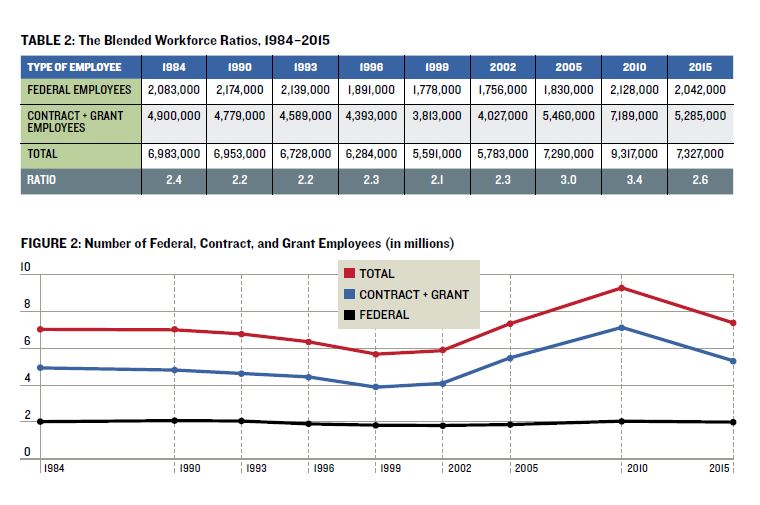

Contrary to those in the Trump administration who have argued there was a “dramatic expansion in the federal workforce” during the Obama administration, the data presented in Tables 1 and 2 show that the number of federal, contract, and grant employees held steady from 1984 to 1994; dropped from 1995 to 1999; increased slightly between 1999 and 2002; surged to a record high between 2002 and 2010; then fell between 2010 and 2015. The end of the Cold War and subsequent defense downsizing generated the first period of decline, while the wars on terrorism and Obama’s economic stimulus plan produced the long period of growth, and the unwinding of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and stimulus spend down spurred the second period of decline. What went up during war and economic stimulus fell when the wars and economic crises cooled.

Table 1 measures the true size of government by the total number of full-time-equivalent federal, contract, grant, Postal Service, and active-duty military personnel. Table 2 removes Postal Service and active-duty military personnel from the totals to measure the ratio of contract and grant employees to federal employees as a quick guide to the changing balance of the government’s blended workforce. As Table 2 shows, the ratio was low and stable from 1984 to 2002, surged in 2005, reached a three-decade high point of 3.4 contract and grant employees for every 1 federal employee in 2010, then fell back toward the historical average in 2015.

Neither table contains jobs created in the wake of household spending by federal, contract, or grant employees. This induced employment may be a product of direct or indirect contracts and grants, but the sandwich makers, business executives, bank officers, and ticket takers who depend on the take-home income created by federal, contract, and grant employees cannot be considered federal employees of any kind. Stripped of induced employment, the estimates presented in Table 1 and 2 provide an apples-to-apples comparison of the true size and blend of the federal government’s workforce.

A Brief History of Washington’s Blended Workforce

Washington’s blended workforce does not expand and contract by accident, but presidents may have less control over its size than they believe. As the following history strongly suggests, war and peace play a much more important role in shaping the true size of the federal government’s blended workforce than grand announcements of caps, cuts, and freezes on federal hiring. Presidents can and do affect the pace of growth and decline, however, and almost always take aim at big government even when they intend to expand it. The following pages discuss this history by administration over the past four decades.

Ronald Reagan

The third year of Ronald Reagan’s administration provides the starting point for a contemporary history of Washington’s blended workforce. As Table 1 shows, the total number of federal contract, grant, military, and Postal Service employees reached almost 10 million in 1984, as Reagan approached the midpoint of his administration, and had barely changed by 1990.

Although the ranks of federal, Postal Service, and grant employees had risen, the number of active-duty military personnel and contract employees had fallen as the post–Cold War demobilization began.

As Table 2 shows, the ratio of federal employees to contract and grant employees was relatively steady from 1984 to 2002; surged from 2002 to 2005 as US troops, defense contract employees, and a small number of grant employees were sent to Iraq and Afghanistan; surged again after Obama launched his $830 billion grant-filled stimulus plan in 2009; and had dropped back to historic trends by 2015. Setting aside the 2005 and 2010 increases as the result of war and economic calamity, the ratios have been remarkably stable over time. Although there is a floor on the industrial side of Washington’s blended workforce, substantial numbers of contract and grant employees reside in a surge tank that rises and falls.

In a sense, there were two Reagans: the defense hawk and the budget cutter. Measured in constant dollars from 1981 to 1989, Reagan increased the defense budget by almost $200 billion between 1981 and 1985 but cut the budget by about $75 billion from 1985 to 1989. In doing so, Reagan proved that even a defense hawk can tame the defense budget without sacrificing readiness. According to the Center for American Progress, almost 90 percent of his cuts came from the defense procurement budget, which dropped from $170 billion in 1985 to $121 billion in 1989.9 Reagan approved a small reduction in the number of active-duty military personnel and began the downsizing that eventually reduced defense civilian employment by a third.

George H. W. Bush

President George H. W. Bush separated himself from his predecessor’s rhetoric during the 1988 Republican campaign by promising a “kinder, gentler nation,” “a thousand points of light,” and a positive role for government. “Does government have a place?” he asked. “Yes. Government is part of the nation of communities—not the whole, just a part. I do not hate government. A government that remembers that the people are its master is a good and needed thing.”

Bush also issued the audacious pledge that would eventually doom his reelection. “The Congress will push me to raise taxes, and I’ll say no,” he promised the party faithful. “And they’ll push, and I’ll say no, and they’ll push again, and I’ll say to them, ‘Read my lips: no new taxes.’”

However, Bush already knew that he could not honor his “no new taxes” pledge unless he balanced the federal budget. He also knew that spending cuts and government downsizing offered the only path to success. Yet, given his commitment to public service as “a noble calling and a public trust,” Bush seemed reluctant to impose new caps, cuts, and freezes. The post–Cold War peace dividend offered the only path to scaling back Washington’s blended workforce.

Bush decided to reap the dividend with a 25 percent drawdown in active-duty military personnel and an equal cut in defense spending. He put the cuts on the implementation track immediately after his inauguration in 1989.14 He placed a one-year freeze on military spending in 1989, began withdrawing forces from Europe to “more appropriate levels” in 1990, negotiated a nuclear weapons treaty with Russia in 1991, and put more cuts “in train” in 1992.

Bill Clinton

The peace dividend was ready for further harvesting when Bill Clinton took office on January 20, 1993, and he began the work immediately with a White House hiring freeze and a 100,000-person cut in the number of federal employees. Clinton expanded the effort by asking Congress to give him the authority to increase the cut to 273,000 under the Federal Workforce Restructuring Act of 1994. Clinton signed the bill only one year into his presidency but claimed victory in his battle against big government:

"After all the rhetoric about cutting the size and cost of government, our administration has done the hard work and made the tough choices. I believe the economy will be stronger, and the lives of middle-class people will be better, as we drive down the deficit with legislation like this. We can maintain and expand our recovery so long as we keep faith with deficit reduction and sensible, fair policies like this."

Clinton claimed credit for this harvest, but Vice President Al Gore did the hard work through his National Performance Review, commonly referred to as “reinventing government.” Gore and his reinventors used the employment ceilings embedded in the Workforce Restructuring Act to press for maximum cuts; accelerated the procurement process ordered by the Federal Acquisition Streamlining Act of 1994; targeted 200 military installations for closure under the Base Closure and Realignment Act; demanded performance plans from every department and agency under the Government Performance and Results Act of 1993; and eliminated the equivalent of 640,000 pages of agency rules under the regulatory planning process created by executive order.

George W. Bush

George W. Bush entered the White House a most fortunate president. He inherited not only a $128 billion surplus but a blended workforce headcount that was 600,000 smaller than George H. W. Bush’s had been at the end of his term. He had room to maneuver as he entered office after an economic boom under Clinton.

Bush showed little interest in further downsizing as he prepared for his inauguration. Clinton had already harvested most of the peace dividend, represented in the smallest blended workforce headcount in recent history. By the end of his presidency, the total number of federal, contract, and grant employees hovered near a twenty-year low, and Washington’s blended workforce seemed to be moving toward the proper meshing.

Bush did not enter office expecting to become a war president. He was as shocked as the nation by the terrorist attacks, and he could not have known that he would send US troops to war in Iraq or that defense spending would rise 30 percent over his first three budgets. Having started with Clinton’s defense cuts, Bush pushed defense spending to $450 billion in 2002, $492 billion in 2003, and $531 billion in 2004—almost all in response to 9/11. Nondefense spending would rise almost 18 percent during the same period as he pursued several relatively expensive domestic priorities, including the Transportation Security Administration, a new farm bill, education reforms, and Medicare prescription drug coverage.

As went the defense budget, so went the blended workforce headcount. The Bush administration added almost 1.4 million contract and grant employees to Washington’s blended workforce just between 2002 and 2005. With that large increase, the percentage of contract and grant employees as a share of the blended workforce also grew significantly as the wars expanded. Whereas there were 2.3 contract and grant employees for every federal employee in 2002, the ratio was 3 to 1 in 2005.

Barack Obama

If George W. Bush had entered the White House a fortunate president, Barack Obama arrived at a most unfortunate time. The economy was reeling in the wake of the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis, the federal deficit was headed toward $1.5 trillion with the debt rising quickly, and credit markets were frozen. The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan still raged. And three of Obama’s cabinet nominees withdrew from consideration amid scandal or under political pressure. His honeymoon period seemed to be over before it began.

Obama showed no sign of worry on February 24, 2009, however, when he appeared before Congress to deliver his economic recovery plan. After all, he already knew that he would receive a peace dividend by ending the 2008 troop surge that Bush had launched six months before the election. Obama cast the coming cuts as an opportunity to reshape government. Speaking to the University of Michigan’s class of 2010, he rejected the traditional argument about big and small government: “The truth is, the debate we’ve had for decades now between more government and less government, it doesn’t really fit the times in which we live. We know that too much government can stifle competition and deprive us of choice and burden us with debt.”

Donald Trump

Donald Trump did not mention the government-industrial complex in any form during the 2016 campaign or his transition into office, but he did discuss each side of the complex separately. On the industry side, he criticized Boeing for overpricing the new Air Force One: “Boeing is building a brand new 747 Air Force One for future presidents, but costs are out of control, more than $4 billion. Cancel Order!” he tweeted on December 6, 2016.21 In another tweet on December 12, Trump targeted Lockheed Martin for overpricing the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter: “The F-35 program and cost is out of control. Billions of dollars can and will be saved on military (and other) purchases after January 20th.”22 Lockheed stock fell 2 percent later that day and fell 1 percent after Trump repeated his commitment to cost savings in early January.

On the government side, his Contract with the American Voter listed a federal hiring freeze as a solution to “corruption and special interest collusion.” As former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich wrote at the time, the promise would reassure mainstream Republicans that Trump deserved their support:

"Trump’s Contract with the American Voter should also alleviate any concern among traditional Republicans that their party’s candidate is somehow not Republican enough. The provisions in the Trump Contract would reduce the size and scope of government as much as any president in our lifetimes, including Ronald Reagan. Its ethics reforms and bureaucracy-cutting measures would significantly reduce the power of the executive branch Trump seeks to lead."

Even as Trump accused contract firms of price gouging, he blamed the federal government for waste, fraud, and abuse. Asked in a February 2016 debate how he would balance the federal budget, he blamed agencies. “Waste, fraud, and abuse all over the place,” he answered, “Waste, fraud, and abuse. You look at what’s happening with every agency—waste, fraud, and abuse. We will cut so much, your head will spin.”

Asked two weeks later how he would pay for his tax cuts, Trump again put the burden on government. “We’re going to buy things for less money,” he answered. “We will save $300 billion a year if we properly negotiate. We don’t do that. We don’t negotiate. We don’t negotiate anything.”

The First 100 Days Trump followed through on his complaint on January 23, 2017, when he imposed a 90-day “across-the-board” freeze on civilian hiring. He signed the order without remarks, but the administration framed the memorandum as a broad attack on big government. “Look, I think you saw this with the hiring freeze,” the president’s press secretary, Sean Spicer, explained later in the day. “There’s been frankly, to some degree, a lack of respect for taxpayer dollars in this town for a long time, and I think what the president is showing through the hiring freeze, first and foremost today, is that we’ve got to respect the American taxpayer. They’re sending us a ton of money; they’re working real hard.”

Though perfectly legal, the freeze exempted thousands of national security and public safety positions, and it had little effect on nondefense employment. Relatively few federal employees leave their posts in winter, and most of the vacancies were filled by an unknown number of service contract employees.28 Brief though it was, the freeze created an atmosphere that one employee likened to the theme music in Jaws.

The uncertainty increased when Trump signed Executive Order 13781 in March. Designed to “improve the efficiency, effectiveness, and accountability of the executive branch,” the order gave the Office of Management and Budget (OMB ) authority to develop plans, as appropriate, to eliminate or merge whole agencies, pieces of agencies, or agency programs. The order also asked the OMB director to pose three broad questions about government performance:

- Whether some or all of the functions of an agency, a component, or a program are redundant, including with those of another agency, component, or program;

- Whether certain administrative capabilities necessary for operating an agency, a component, or a program are redundant with those of another agency, component, or program; and

- Whether the costs of continuing to operate an agency, a component, or a program are justified by the public benefits it provides.

The answers were not due for 180 days, but the future became clear when Trump released his 2018 “skinny budget” on March 16. Although best described as a wish list of future priorities, the budget outline contained a $54 billion increase in defense spending to honor the president’s promise to make the military “so strong ... nobody’s gonna mess with us,” and a parallel cut in nondefense programs and agencies that included the State Department.

Congress would have to approve the proposals, but all things being equal transaction by transaction, the defense increase would almost certainly raise the number of contract and grant employees on the industry side of the federal workforce, while the domestic cuts would almost certainly reduce the number of federal employees on the government side. Fortune estimated that the cuts could eliminate 100,000 to 200,000 jobs, which former Clinton administration budget director Alice Rivlin described as “drastic layoffs that would be very hard to do very quickly.” Stories about nervous, even terrified, federal employees hit the front pages again, but the effects on the total number of federal employees were ambiguous at best.

However, the administration made no secret about the depth of the cuts in what OMB Director Mike Mulvaney called the “America First Budget:”

"The president’s commitment to fiscal responsibility is historic. Not since early in President Reagan’s first term have more tax dollars been saved and more government inefficiency and waste been targeted. Every corner of the federal budget is scrutinized, every program tested, every penny of taxpayer money watched over."

Mulvaney stretched the history-making timeline all the way back to George Washington when he later said the “skinny budget” would stop 240 years of organic growth in government: “The president of the United States has asked all of us in the executive branch to start from scratch, a literal blank piece of paper, and say, ‘If you’re going to rebuild the executive branch, what would it look like?’”

Finally, Mulvaney explained the president’s decision to end his 90-day hiring freeze as a natural product of organizational learning:

"So we’re going from this sort of across-the-board hiring freeze. That’s not unusual for any new management team to come in—to put into place when they come into an organization, whether it’s the private sector or a government. Not unusual for a new management team to come in and say, look, stop hiring, let us figure out what’s going on, we’ll get acclimated and then we’ll put into place something that’s more practicable and smarter. And that’s what this is. So you’ll see this across-the-board ban tomorrow and replaced with a smarter approach."

Reinventing Government? If there was any comfort for anxious federal employees in the budget messaging, it came in the president’s statements in early March supporting a government that works better and costs less. “We are going to do more with less, and make the government lean and accountable to the people,” Trump wrote in his budget message to Congress. “Many other government agencies and departments will also experience cuts. These cuts are sensible and rational. Every agency and department will be driven to achieve greater efficiency and to eliminate wasteful spending in carrying out their honorable service to the American people.”

The president had not become a reinventor per se, but he did promise to do something “very, very special” to make government more efficient and “very, very productive.”37 In doing so, he even prompted some of Gore’s reinventors to endorse the effort. As Elaine Kamarck, chief staffer to the former vice president, told Politico in March, “To give them credit, it’s time to do it again. It is time to review the government again and ask the hard questions about what it’s doing and what it should be doing. And it is time to focus on obsolete functions and getting rid of them.”

Trump may have used reinventing’s “works-better-and-costs-less” cadence, but his definition of a government that works better and costs less was a government that cost less because it was no longer working.

On the government side of the complex, for example, his 2018 budget targeted nondefense federal employees for deep reductions in force. The administration did not set a specific downsizing target, but it ordered all departments to identify opportunities for attrition-based workforce cuts. The budget also scheduled wholesale cuts in nondefense programs such as environmental protection and Medicaid.

On the industry side, the budget gave contract and grant employees cause for joy. It offered 40 percent more for defense operations and maintenance, 20 percent for research and development, and 6 percent for procurement. Meanwhile, the budget promised the Army, Navy, and Air Force increases of 55 percent, 49 percent, and 46 percent, respectively, foroperations and maintenance; somewhat smaller increases for Air Force and Navy research and development; and 16 percent for Navy shipbuilding and conversion. These increases all promised large hikes in the contracting and grant workforce.

Deconstructing the Administrative State The number of nondefense federal employees could fall much further in subsequent years if Trump pursues his early plan to “deconstruct the administrative state.” Conservatives commonly use the term to describe the wholesale dismantling of the “deep state” that generates government growth and interference. The president endorsed dismantling when he appointed Stephen Bannon to the White House staff. Bannon used his close ties to Trump’s right-wing base to press for administrative and regulatory reform. Speaking at the Conservative Political Action Conference in late February 2017, he described deconstruction as the third “bucket” of the president’s America first agenda:

"The third, broadly, line of work is deconstruction of the administration. … If you look at these cabinet appointees, they were selected for a reason, and that is the deconstruction. The way the progressive left runs, is if they can’t get it passed, they’re just going to put in some sort of regulation in an agency. That’s all going to be deconstructed, and I think that that’s why this regulatory thing is so important."

Bannon had been forced out of the administration by August 2017, but his deconstruction agenda was widely shared by other senior officials, including Mulvaney and his team of budget cutters. Mulvaney did not use the term specifically, but he shared Bannon’s concern when he described executive orders as a poor substitute for legislative success:

"To the extent that we only do stuff within the executive branch—as with any executive orders—they can be overturned by the next administration if they see things differently. That’s the way the executive order system works. And that if we wanted real permanent change, the best way to go about that would be to do legislative change."

Trump had already started the deconstruction by using his pen to establish a travel ban on migrants from seven Muslim-majority countries; establish Regulatory Reform offices across the government; develop construction plans for a wall between Mexico and the US ; create an Office of American Innovation—led by his son-in-law and White House aide, Jared Kushner; and require every department and agency to develop reorganization plans.

The president also encouraged Congress to use the obscure Congressional Review Act to roll back Obama’s contracting orders.43 Trump’s first target was Executive Order 13673, which required contract bidders to disclose any labor law violations in the three-year period prior to the solicitation. Federal contract officers were ordered to use the information to assess the bidder’s record of integrity and business ethics; determine whether the violations were serious, willful, repeated and/or pervasive; and list the findings on the federal government’s Awardee Performance and Integrity Information System for other departments and agencies to use. Firms with violations could still bid for contracts, but the rule sent a clear warning that violations could matter in the final decision.

Trump had promised to revoke the so-called blacklisting rule during the campaign, and he welcomed business leaders to the Oval Office on March 27, 2017, when he sat down to sign the rollback:

"When I met with manufacturers earlier this year—and they were having a hard time, believe me—they said this blacklisting rule was one of the greatest threats to growing American business and hiring more American workers. It was a disaster, they said. This rule made it too easy for trial lawyers to get rich by going after American companies and American workers who contract with the federal government—making it very difficult."

Democrats and labor unions did not agree. With the revocation bill already on the president’s desk awaiting signature, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) released a caustic report, Breach of Contract: How Federal Contractors Fail American Workers on the Taxpayer’s Dime. Drawing on federal databases, congressional investigations, and the Federal Contractor Misconduct Database of the nonprofit Project for Government Oversight (POGO), the report concluded that “the violation of labor laws and abuse of workers by federal contractors is common, repetitive, and dangerous.” While acknowledging that contract firms supported critical federal missions, Warren said they often did so by underpaying workers and putting health and safety at risk. She warned her colleagues that the risks would rise if contract firms took the rollback as permission to reduce employee protections even further.

Breach of Contract was too late to make a difference in Trump’s decision or media coverage. As the president indicated at his signing ceremony, Obama’s Fair Pay and Safe Workplaces rule was only the first of many rollbacks ahead: “I will keep working with Congress, with every agency, and most importantly, the American people, until we eliminate every unnecessary, harmful and job-killing regulation that we can find. We have a lot more coming.” He had inherited Obama’s pen and intended to use it toward a very different end.

An Inventory of Pressures

Many appropriate reasons exist for using contract and grant employees to help execute the laws—not the least of which is the need for mission-critical skills—but convenience is not one of them. As the following discussion suggests, however, convenience may be the only available criterion given the demographic, bureaucratic, and political pressures that weaken the case for using federal employees. There is little opportunity for more thoughtful analysis in an antiquated federal personnel system. There’s also continued ambiguity about the dividing line between functions so important to the public interest that they must be reserved for federal employees and those functions that are not inherently governmental and can be purchased more economically from a commercial source.

Five Demographic Pressures

Demographic change creates five pressures for pulling contract and grant employees across the dividing line from a commercial source: (1) the federal government’s sluggish hiring process, (2) aging workforce, (3) high promotion speed, (4) inflated performance appraisals, and (5) easy access to the hidden bureaucratic pyramid of contract and grant employees who fill the mid- and lower-level jobs once held by federal employees.

1. Waiting for Arrival

There are many ways to measure the hiring delays, but time to hire is the simplest statistic. In theory, applicants should move from application to “onboarding” without delay. In reality, the federal government continues to impose time penalties at every step of the process. Although the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) stopped publishing government-wide time-to-hire statistics when its priorities switched from hiring speed to candidate quality, the best available evidence suggests that the hiring process in the federal government is two to three times as long as that in colleges and universities, franchises, hospitals, and private and public companies.

The Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs took note of time and frustration when it moved its Federal Hiring Process Improvement Act to the floor in May 2010:

"Those seeking federal employment have long faced an opaque, lengthy, and unnecessarily complex process that ultimately serves the interests of neither federal agencies nor those seeking to work for them. ... Weak recruiting, unintelligible job announcements, onerous application requirements, an overly long hiring process, and poor communications with applicants deter potential candidates from applying and cause many of those who do apply to abandon the effort before a hiring decision is made."

The Obama administration also took note of time when it launched the first of its threehiring reforms in May 2010. “I understand the frustration of every applicant who previously has had to wade through the arcane Federal hiring process,” said John Berry, the OPM director. “If qualified applicants want to serve our country through the Federal service, then our application process should facilitate that.” The commitment was strong enough to persuade Congress to shelve the Senate’s bill but not strong enough to move the federal hiring model from “post and pray” to “post and pursue.”

Despite recent congressional hearings with hopeful goals such as Jobs, Jobs, Jobs: Transforming Federal Hiring and Uncle Sam Wants You: Recruitment in the Federal Government, comprehensive reform remains a distant goal. Even the federal government’s ongoing overhaul of its sluggish one-stop hiring platform, USAJobs, is unlikely to have an impact if its “human-centered design” does not lead to good jobs.

At least for now, USAJobs is more a disappointment than a source of pride. As one expert told a Senate roundtable in 2016, “USAJobs has become home to a seething group of confused and angry job seekers and fulfills a main purpose for a limited set of people desperately seeking any kind of employment or those who don’t really know what job they seek.” Other witnesses showed more respect toward the 11 million USAJobs account holders, as did Washington Post columnist Joe Davidson, but all agreed the system had to change.

2. Aging Upward

As the federal workforce continues to age, government is edging toward what experts have described as a “retirement tsunami” created by older federal employees. The percentage of younger federal employees has fallen in recent years, while that of older employees has risen. Though older employees have shown remarkable staying power during good times and bad, they are moving closer to retirement.

According to data collected by Jeff Neal, founder of ChiefHR O.com, the percentage of federal employees under 30 has been on a straight downward trend—from 11.4 percent in 2009 to 9.8 percent in 2012 and just 7.9 percent in 2015.56 Translated into headcounts, the number of federal employees under 35 dropped from 230,000 to 160,000 during the period, while the number of federal employees over 60 rose from 225,000 to 278,000.57 Expand the numbers to include all employees over 55 and these numbers soar from 380,000 in 2009 to 520,000 in 2015.

The 2003 National Commission on the Public Service, chaired by Paul A. Volcker, summarized the data as a classic catch-22: As the government’s experienced workers depart for retirement or more attractive work, it creates an opening for new energy and talent; yet the replacement streams are drying up. Left unchecked, these trends can lead to only one outcome: a significant drop in the capabilities of our public servants.

The retirement wave will also prompt employee shortages at the midlevels of government retirement, where so many contract and grant employees work. Service contract employees rarely reach the top of the federal hierarchy but often perform tasks that would have been reserved for younger federal employees as they moved up the chain of command toward more senior positions. Absent a steady pipeline of committed employees, federal managers and supervisors have little choice but to call for help. The employees who show up are often well-qualified for the work, but they cannot take higher-level posts without breaching the dividing line. They also create dependency that managers and supervisors cannot easily break.

3. Promotion Speed

Age is significantly related to federal pay grades—the longer employees stay, the more likely they are to advance up the federal government’s fifteen pay grades and across the ten steps within each grade. Advancement from one step to the next is almost always automatic after one to three years on the job, while promotions up the ladder can be fast or slow depending on vacancies and the candidate’s education, eligibility, and experience. As older employees move across the steps and up the ladder, they pull lower-level employees across and up, too.

Promotion speed can be used to battle employment caps, cuts, and freezes through backdoor pay increases but also can give federal employees the titles and prestige to stay put, despite the opportunity for higher-paying positions in contract or grant positions. As a former senior officer in the Officer of Personnel Management recently recalled, the movement of talented employees to contract and grant posts increased promotion speed as a retention strategy: “This pressure comes not only from employees but from management as well. Supervisors use constant upgrades as a retention strategy, especially for employees in technical and hard-to-fill positions.” Even if promotion speed is used to retain and reward the most talented employees, it weakens the chain of command and produces government failures, such as the failure to connect the dots that led to the 9/11 attacks and the sluggish response to Hurricane Katrina. It also encourages the use of contract and grant employees to backfill vacated posts.

4. All Above Average

The federal performance appraisal system was designed to rate and reward employee contributions to department and agency goals. In theory, the system creates a “line of sight” between what individual employees do and how their organizations perform. Although a small number of employees are covered by pass/fail systems, the vast majority are covered by a five-level system running from an “unacceptable” rating at the bottom to an “exceeds fully successful” rating at the top.

In theory, the system would provide the guidance needed for disciplined reviews and maximum improvement. In reality, the guidance is so fuzzy and the discipline so weak that federal employees are almost all above average. In 2013, for example, a third of federal employees were rated as “outstanding,” slightly more than a quarter as “exceeds fully successful,” and almost two fifths as “fully successful.” Many federal employees appear to view a “fullysuccessful” rating as a sign of failure and an “outstanding” as an easy mark.

Even the federal government’s prestigious Senior Executive Service (SES ) has its own appraisal inflation. In 2013, 45 percent of SES members were ranked at the highest level of performance and another 44 percent were ranked just below. Although the SES attracts many of the most talented employees in the world, its appraisal system is widely disparaged—even ridiculed—and suggests that performance ratings and actual performance are loosely coupled.

Many federal employees appear to share the assessment. According to the federal government’s annual surveys of its employees, most understand what they have to do to be rated at different performance levels, but many doubt performance matters to pay or recognition. In 2016, for example, just 41 percent said awards depended on how well employees performed their jobs, 34 percent said differences in performance with their work units were recognized in a meaningful way, and 29 percent said steps were taken to deal with a poor performer who cannot or will not improve.

Federal employees are right to dispute the link between performance and discipline. They can be fired, but the process takes time, careful documentation, and persistence. According to a 2015 analysis by the US Government Accountability Office (GAO), the process can take from 170 to 370 days, depending on the statutory authority used to support the dismissal. The process is much easier in the first few months of an employee’s tenure but becomes more difficult as grade inflation takes hold. “The civil service needs to find a way to do an honorable discharge,” one federal human capital officer told the Partnership for Public Service in 2014. “More than hiring reform, we need firing reform. In that reform you need to one, address poor performers and two, address skills that become outdated from otherwise good performers. There are just simply way too many hoops.” Federal employees must be protected against harassment, discrimination, and political interference of the kind witnessed early in the Trump administration, but they must all be accountable for their performance.

5. The Hidden Pyramid

Demography and history come together to reshape the federal hierarchy—employees grow older, missions expand and contract, personnel policies shift, new technologies emerge, and jobs evolve. The changes are easy to track with the number of technical, administrative, clerical, and blue-collar positions at any given point in history.

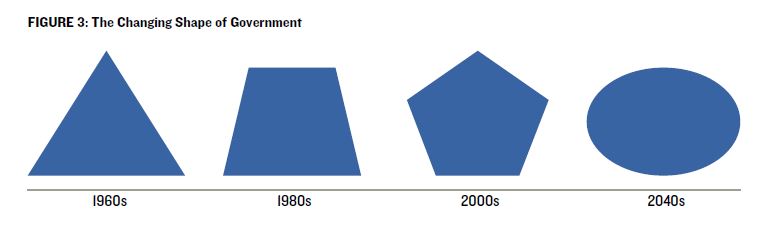

- In 1940, the federal hierarchy looked like a standard bureaucratic pyramid, with most employees at the bottom and a small number of supervisors, managers, and presidential appointees sorted in decreasing numbers above.

- By 1960, the federal hierarchy still looked like a pyramid, but the distance between the bottom and top was starting to increase as new layers of professional and technical employees arrive.

- By 1980, the federal hierarchy was changing from a pyramid to four-sided trapezoid, with roughly equal numbers of federal employees working at the bottom, middle, and top of the hierarchy.

- By 2000, the federal hierarchy looked like a pentagon, with more federal employees working at the middle and top than at the bottom.

- By 2040, the federal hierarchy could evolve into an oval if current trends continue.

Public administration scholar Donald Kettl tracks this “upward creep” by average employee grade, which rose from 6.7 in 1960 to 10.3 in 2014, and attributes it to the federal mission and contracting out:

"The big story overall is that federal employment has hovered around two million workers, but spending, after inflation, has risen sharply. The same number of federal employees is leveraging an ever-growing amount of money, ... This is a direct result of the federal government’s increasing use of proxies, as more of its work was done outside the federal government—and by the accelerating underinvestment in the people needed to do the work."

Kettl’s trend line is an artifact of the rising number of service contract employees who now fill many of the midlevel and lower level jobs once filled by federal employees. The federal hierarchy looks as if it is changing shape largely because contract and grant employees work in a hidden bureaucratic pyramid that hides the federal government’s need for reform.

This is not to suggest that the federal government still employs large numbers of couriers and stenographers—those jobs are gone for good. However, the data suggest that the federal government still employees its fair share of lawnmowers, mapmakers, statisticians, accountants, repair specialists, and cafeteria workers. Their checks may not come directly from the Treasury, but they will help the federal government execute the laws until Silicon Valley invents an app for that.

The federal government may not know precisely how many employees work in this hidden pyramid, but it does know that millions of employees show up every day to do work once performed by federal employees. The decision to separate these employees from the federal headcount perpetuates the conceit that government can do more with less ad infinitum, and encourages departments and agencies to create their own systems for managing the workload. As the National Academy of Public Administration recently concluded, the absence of reform has produced chaos:

"Among its many problems, the current civil service system is no longer a system. It is mired in often-arcane processes established after World War II, in the days before the Internet, interstate highways, or an interconnected global economy. Pursuit of those processes, many now largely obsolete, has become an end in itself, and compliance with them has tended to come at the expense of the missions they were supposed to support. As a result, the federal civil service system has become a non-system: agencies that have been able to break free from the constraints of the outmoded regulations and procedures have done so, with the indulgence of their congressional committees."

Five Bureaucratic Pressures

The federal government’s bureaucratic routines create another five pressures for pulling contract and grant employees across the government-industrial dividing line: (1) skill gaps in mission-critical occupations, (2) barriers to federal employee engagement, (3) apples-tooranges pay comparisons, (4) weakened internal oversight, and (5) the sluggish presidential appointments process.

1. Hollowing Out

Many of the demographic problems discussed above affect skill sets such as cybersecurity, telecommunications, acquisitions, information management, and even project planning. The GAO put the gap between demand and supply for mission-critical positions on its high-risk list in 2001.70 According to the office, the cascade of human capital problems such as skill imbalances, understaffing, and grade inflation had finally crossed the threshold into a systemic crisis: “The combined effect of these challenges serves to place at risk the ability of agencies to efficiently, economically, and effectively accomplish their missions, manage critical programs, and adequately serve the American people both now and in the future.”

With due respect to the GAO’s caution, its decision came more than a decade after Volcker and his first National Commission on the Public Service warned Congress and the president in 1989 about the “quiet crisis” at the intersection of declining student interest and retirement pressure:

"Simply put, too many of the best of the nation’s senior executives are ready to leave government, and not enough of its most talented young people are willing to join. This erosion in the attractiveness of public service at all levels—most specifically in the federal civil service—undermines the ability of government to respond effectively to the needs and aspirations of the American people, and ultimately damages the democratic process itself."

Now, after 30 years and another demand for action by a second Volcker Commission, most departments and agencies are still struggling to implement effective policy. Although the GAO applauded the government’s commitment to action, it also noted that skill gaps were contributing causes to fifteen of the thirty-three other items on its high-risk list: “Regardlessof whether the shortfalls are in such government-wide occupations as cybersecurity and acquisitions, or in agency-specific occupations such as nurses at the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), skills gaps impede the federal government from cost-effectively serving the public and achieving results.”73 The collateral damage is almost certain to increase as federal retirements increase in coming years.

2. The Engagement Gap

Employee engagement is essential for high performance in any public service organization, be it governmental, nonprofit, educational, or the public-private partnerships that formed the centerpiece of the Trump administration’s 2017 infrastructure plan. In turn, employee empowerment and the inspiration for change are the two major drivers of engagement. Employees must have confidence that their organization will provide them with the resources and opportunity to succeed.

OPM’s 2016 Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey (FEVS) showed little of this confidence, however. Engagement did increase between 2013 and 2016, but by just one percent. The OPM director described the 2016 results as a sign of government’s success in “empowering employees and inspiring change,” but the 420,000 federal employees who took the survey expressed doubts about both goals.

Start with the FEVS questions about empowering employees. According to the survey, less than half of respondents were satisfied with the information they received from management (48 percent), had sufficient resources to do their jobs (47 percent), felt personally empowered with respect to work processes (45 percent), believed their organization recruited people with the right skills (43 percent), worked in units where employee performance was recognized in a meaningful way (34 percent), thought their work units took steps to deal with

poor performers who could not or would not improve (29), and said pay raises depended on how well employees do their jobs (22 percent).

Turn next to the FEVS questions about inspiring change. According to the survey, less than half of respondents were recognized for providing high-quality products and services (48 percent), felt acknowledged for doing a good job (48 percent), were satisfied with the policies and practices of their senior leaders (42 percent), worked for leaders who generated high levels of motivation and commitment (41 percent), felt rewarded for their creativity and innovation (38 percent), believed they had the opportunity to get a better job in their organization (36 percent), and thought promotions were based on merit (32 percent).

Despite their concerns, the respondents were generally positive about their own performance on the job. Substantial majorities said they were ready to put in the extra effort to get the job done (92 percent), were held accountable for results (82 percent), were judged fairly on performance (70 percent), had a sense of personal accomplishment at work (72 percent), were satisfied with their jobs (66 percent), would recommend their organization as a good place to work (64 percent), and were encouraged to come up with new and better ways of doing things (58 percent). In a sentence, federal employees believe they create impact every day but that they must do so against the odds.

These attitudes create a significant “engagement gap” between federal and private employees that led the Partnership for Public Service to declare an urgent need for progress on the work environment. According to the Partnership’s analysis of the 2016 FEVS survey, engagement in the federal workplace trailed that in the private sector by an average of 13 percentage points on twenty-five key questions.

On the one hand, both groups of employees expressed similar levels of confidence in their opportunity to improve their skills, in their belief that performance appraisals were fair, in their access to information, and in their feeling of personal accomplishment. On the other hand, the private sector employees were more positive than federal employees on all twenty-five of the comparison questions, with particularly significant gaps on eight items:

- I am satisfied with the training I receive for my present job: +11 percent

- Supervisors in my work unit support employee development: +11 percent

- I can disclose a suspected violation of any law, rule, or regulation without fear of reprisal: +16 percent

- My workload is reasonable: +14 percent

- I feel encouraged to come up with new and better ways of doing things: +20 percent

- My talents are used well in the workplace: +22 percent

- Awards in my work unit depend on how well employees perform their jobs: + 24 percent

- I have sufficient resources (for example, people, materials, budget) to get my job done: +24 percent

Private sector employees might not have had such fulsome praise for their organizations and leaders if they worked under the same stresses as federal employees. The federal mission is broad but sometimes poorly specified, the customer base is often divided, the board is almost perfectly designed to split, funding is taut, and political pressures are undeniable. The disparities help explain the empowerment denied and the change dismissed in government.

3. Compensation Versus Cost

Contract and grant employees are often promoted as a low-cost alternative to federal employees, but the data suggest quite the opposite. Federal employees may seem more expensive than contract and grant employees on average but may be much less expensive than contract employees when compared occupation by occupation. POGO made this case in the 2011 report Bad Business: Billions of Taxpayer Dollars Wasted on Hiring Contractors. The research was designed to challenge the long-standing assumption that the federal government saves money when it hires contract employees in lieu of federal employees. According to POGO’s comparison of thirty-five occupations, including auditor, groundskeeper, statistician, and technical writer, the assumption is based on a false equivalency. POGO’s data showed that federal employees had higher compensation in twenty-six of the occupations but that private sector employees cost more than federal workers in thirty three of the thirty-five jobs.

The explanation is in billing rates, not paychecks: Contract employees are less expensive only until overhead—or indirect costs such as supplies, equipment, materials, and other costs of doing business—enter the equation. Add overhead to the totals, and contract employees can cost twice as much as federal employees. If the issue is how to reduce taxpayer burdens, federal employees were often the better option:

"POGO’s findings confirm the basic premise that government employees are generally compensated at a higher rate than private sector employees. However, in the 35 occupational classifications and 550 specific jobs POGO analyzed, reliance on contractor employees costs significantly more than having federal employees provide similar services. As a result, taxpayers are left paying the additional costs associated with corporate management, overhead, and profits that the government has no need to incur."

The conventional wisdom regarding the cost of contracting was not shaken. The contracting industry denied the findings and rebutted the methodology. The report was “a smear on industry” and based on the “irrelevance of averages,” the Professional Services Council said.

"POGO’s conclusions are based on data purporting to show that “on average” contractors are more expensive than government performance of the same or similar work. Yet as a decision-making tool, averaging has little value or relevance since it offers no perspective or insight. Even if one assumes the baseline data is complete and accurate, all the POGO report shows is that sometimes contracting is more expensive than government performance and sometimes not. It does nothing to aid in the government’s determination of where and how best to perform a given requirement."

The antiaveraging argument is particularly interesting given the enduring use of averages to promote contracting out. Writing for the libertarian Cato Institute in September 2017, Chris Edwards reported that federal employees averaged $88,809 in wages during 2016, compared with private sector employees at $59,458, and that federal employees had also received $38,450 in benefits, compared with private sector employees at $11,306. After referring tothe government’s “extremely high job security” as an additional benefit of federal employment, Edwards acknowledged that “federal pay should be reasonable, and we need competent people in federal jobs.” However, he concluded that “an advantage of reducing federal pay would be to encourage greater turnover in the static federal workforce.” He also argued that the openings might draw young people into government, but did not mention the potential effect of such turnover on federal skill gaps.

Edwards’ averages suffered from many of the same complaints the contract industry made against the POGO report. According to the CBO’s analysis of the same Census Bureau data, federal employees with no more than a high school diploma earned 21 percent more per hour on average than private sector employees with the same amount of education, while those with a bachelor’s degree earned about the same per hour, and federal employees with a doctorate or professional degree earned 23 percent less on average.

Averages may be the antonym of nuance but are often used to support federal hiring caps, cuts, and freezes. They also underpin head-to-head, dollar-to-dollar competitions between federal and contract teams to determine which can deliver the same goods and services at the lowest cost using the most-efficient organization possible. These competitions were used most recently by the George W. Bush administration to test its theory that any job listed in the “Yellow Pages” phone directory can be done at lower cost by contract employees.82 Federal employees won 83 percent of the tests, suggesting that they could do the jobs for less when given the opportunity to build a most-efficient organization.

4. Attention Deficits

The federal government’s internal oversight offices are essential for policing the boundaries between government and industry while raising questions about who should do what for how much in faithfully executing the laws. These offices are rarely popular within their own departments and agencies but have generally been left to do their work, with minimal interference.

The Clinton administration was a notable exception. Convinced that oversight offices were the source of wasteful government, the administration opened the reinventing government campaign by promising deep budget and personnel cuts in the number of federal supervisors, personnel specialists, budget analysts, procurement specialists, accountants, and auditors. “We called them the forces of micromanagement and distrust,” one former reinventing official said. “We wanted to reduce the number of inspectors general, controllers, procurement officers and personnel specialists.” Another characterized the offices as part of a “fear industry” relying on “criticism and attacks to beat down employees or managers, and scare them into shape.”

The reinventing campaign had a long list of targets but focused most heavily on the Offices of Inspector General (OIG). Congress created the first OIG in 1976 to unify the scattered audit and investigatory functions within the Department of Health, Education, and had created forty-two by the time Clinton entered office. The inspectors general used their broad investigatory authority to build impressive totals in what they called “funds put to better

use” but also earned a reputation for padding their statistics with small-scale, “gotcha” investigations.

They also became a target for Gore:

"When we blame the people and impose more controls, we make the systems worse. Over the past 15 years, for example, Congress has created within each agency an independent office of the inspector general. The idea was to root out fraud, waste, and abuse. The inspectors general have certainly uncovered important problems. But as we learned in conversation after conversation, they have so intimidated federal employees that many are now afraid to deviate even slightly from standard operating procedure."

Despite its general disparagement of the OIG concept, the Clinton administration gave more weight to audit and investigatory experience in appointing its inspectors general than the George W. Bush administration.89 At the same time, the Clinton administration was much slower than the Reagan, George H.W. Bush, and George W. Bush administrations in filling its empty inspector general posts.

The OIG and other control offices were still under fire in 2015 when, for example, 32 percent of the inspectors general reported that their staffing levels had declined by 5 percent to 10 percent since 2012; 13 percent reported that their declines had exceeded 10 percent. The acquisition and oversight offices were also buffeted by the hiring delays cited earlier and were mentioned frequently as contributors to the GAO’s high-risk list.

5. Nasty, Brutish, and Not at All Short

The delays caused by the presidential appointments process create incentives for outsourcing, including regular vacancies at the top. According to appointments expert Anne Joseph O’Connell, the top jobs in government are vacant between 15 percent and 25 percent of the time, creating enormous upset down the chain of command.91 Although second- and third-tier presidential appointees fill some high-level vacancies, career members of the SES are the default appointees. As such, these career officers are often the key policymakers in government.

Turnover is not the only source of vacancies. According to O’Connell, many presidential nominations are withdrawn, rejected, or dropped at some point in the confirmation process. Setting aside judicial nominations in her analysis of all presidential nominations sent to the Senate between 1981 and 2014, independent regulatory commission nominations had the highest failure rates at 31 percent; followed by White House agencies such as the OMB at 21 percent, executive agencies such as the Environmental Protection Agency at just over 20 percent, and cabinet departments at 19 percent. As for specific positions, general counsels and inspectors general were at 24 percent failure, compared with cabinet secretaries at 9 percent.

The long vacancies not only break the president’s chain of command but can elevate senior executives and their assistants ever higher to fill and support empty positions in an acting capacity. “Given the political impact of presidential appointees on government policy and execution,” presidential appointments expert G. Calvin Mackenzie writes, “one might imagine that the nomination and confirmation process would be tailored for efficiency and effectiveness. But it is actually a vast morass. …”

O’Connell documents the case by counting the mean number of days between nomination and confirmation for the president’s senior officers. According to her precise accounting, the interval has crept ever upward over the past five presidents, rising from just fifty-nine days under Reagan to 127 days under Obama. Trump’s interval is certain to increase even further.

Five Political Pressures

Despite the intense demographic and bureaucratic pressures discussed, five political pressures create even greater incentive to call contract and grant employees across the blended workforce dividing line and weaken the government’s ability to make an intentional choice: (1) the thickening of the leadership hierarchy, (2) the need to protect government achievements and fix breakdowns, (3) public anger and frustration toward government, (4) political polarization, and (5) what Alexander Hamilton called the “most deadly adversaries of republican government.”

1. Thickening Government

Just as demographic pressures can draw contract and grant employees across the government-industrial dividing line, so the past half-century has witnessed a slow but steady thickening of the federal bureaucracy as Congress and presidents have added layer upon layer of political and career management to the leadership hierarchy. Whereas John F. Kennedy entered office in charge of seven cabinet departments in 1961, Donald Trump entered in charge of fifteen. Whereas Kennedy’s cabinet departments had seventeen layers open for new leaders, Trump’s had seventy-one. Finally, whereas Kennedy inherited 451 political or career positions ready for occupancy, Trump inherited 3,265.96 From 1961 to 2016 the number of layers grew 750 percent, while the number of leaders per layer grew by 625 percent.

The thickening occurred in every cabinet department, although there are variations. For example, large, old departments such as Defense and Treasury had more layers and leaders in 2016 than small, new departments such as Commerce and Labor. Nevertheless, a remarkable variety of titles are open for occupancy across the entire cabinet, and the number of layers and leaders rose continually between 1960 and 2016.

Some of the titles may challenge credulity, but all seventy-one exist somewhere in the federal hierarchy. For example, the 2016 federal phone book listed an associate principal deputy assistant secretary at the Energy Department, an associate assistant deputy secretary at the Education Department, a principal deputy associate and a principal deputy assistant Attorney General at Justice, and an associate deputy assistant secretary at Veterans Affairs.

Trump seemed to recognize the potential costs of this thickening when he told Fox & Friends in early March 2017 that he did not want to fill many of the 600 high-level posts still open for occupancy:

"Well, a lot of those jobs, I don’t want to appoint, because they’re unnecessary to have. You know we have so many people in government, even me, I look at some of the jobs and its people over people over people. … There are hundreds and hundreds of jobs that are totally unnecessary jobs."

Trump may have been right to question the need for so many jobs but was wrong to conclude that all the positions were unnecessary or could be eliminated at will. Some were created by statute; others were established through the federal government’s highly formalized classification system, and still others came about by department memoranda.

Most important, those positions are hardwired into a bureaucratic process that links the top of the federal government to the bottom. Trump may have been tempted to leave the posts unfilled, but he could not know which ones were essential without further analysis. These connective positions link the heads of government to the career workforce that must execute the laws and executive actions. As of September 2017, his administration was not so much headless as neckless.

2. Achievements and Breakdowns

Washington’s blended workforce has contributed to many of the federal government’s greatest achievements, such as building the Interstate Highway System, conducting the basic research to help reduce life-threatening disease, exploring space, and administering antipoverty programs. At other times, it has contributed to government breakdowns, including the veterans waiting list scandal; the Deepwater Horizon oil spill; the Challenger and Columbia shuttle disasters; the I-35W bridge collapse; the healthcare.gov launch; Edward Snowden’s security breach; the Abu Ghraib prisoner abuse; the Southwest Airlines grounding; and the fertilizer explosion that destroyed West, Texas.

Paradoxically, both success and failure expand Washington’s blended workforce. The easiest way Congress and the president can make grand achievements even grander is to call on the same contract and grant employees who helped create the successes in the first place. In turn, the most familiar way to repair a breakdown is to call on the same contract and grant employees who may have contributed to the breakdowns. Expertise is the coin of the realm for scaling achievements and fixing breakdowns, and contract and grant employees are often the ones who have the needed skills.

3. Anger and Frustration

Americans have long held seemingly irreconcilable opinions about the federal government and its employees. They seem to hate the federal bureaucracy, but they love its programs and services.

On the one hand, trust in the federal government has been tumbling since Americans rallied together after 9/11. In a Pew Research Center survey in 2015, only 19 percent of respondents said they trusted the federal government to do the right thing just about always or most of the time, versus almost 70 percent who said only some of the time or never. Four in five Americans also said they were either angry or frustrated about government, while three-quarters rated the federal government’s performance in running its programs as only fair or poor. Majorities also said government was almost always wasteful and inefficient, needed major reform, and was doing too many things better left to individuals. Majorities also believed ordinary Americans could do a better job of solving the nation’s problems than elected officials and said the government needs “very serious reform.”

On the other hand, Americans said the federal government should play a major role in addressing almost every problem on the national agenda. Though they were less trusting and more frustrated than they were in the early 2000s, they gave the government generally high marks on responding to natural disasters (79 percent said government was doing a good job); setting workplace standards (76 percent); keeping the country safe from terror (72 percent); and ensuring safe food and medicine (72 percent). In addition, despite giving the federal government much lower marks on managing the immigration system (22 percent), helping people out of poverty (36 percent), ensuring basic income for older Americans (48 percent), and strengthening the economy (51 percent), they wanted it to play a major role in resolving those issues.

Moreover, respondents also expressed positive views toward most departments and agencies in Pew’s 2015 survey. The top ten were the Postal Service, with an 84 percent favorable rating; the National Park Service (75 percent); Centers for Disease Control (71 percent); NASA (70 percent); FBI (70 percent); Homeland Security (64 percent); Defense (63 percent); CIA (57 percent); Social Security Administration (55 percent); and Health and Human Services (54 percent). Justice, Education, the Internal Revenue Service, and Veterans Affairs were the only agencies ranked below 50 percent, but even the IRS earned a 42 percent rating.

Even though the IRS got the lowest approval ratings on Pew’s list, research by Brookings Institution scholar Vanessa Williamson in 2017 suggests that Americans believe paying taxes is part of being a good citizen:

"The idea that ‘Americans hate taxes’ has become a truism without the benefit of being true. Instead, Americans see paying taxes as a civic obligation and a political act. To be a taxpayer, Americans believe, is something to be proud of. It is evidence that one is a responsible, contributing, and upstanding member of society, a person worthy of respect in the community and representation in the government."

4. Polarization

Industry learned long ago that profits depend on at least some certainty about the future, but certainty is a rare commodity in a federal government beset by polarization at every turn of the budget cycle. Given the rising level of congressional gridlock and the potential for deep cutbacks of the type faced in the 2013 government shutdown, it is difficult to criticize the federal government for recruiting contract and grant employees to fill the holes made by caps, cuts, and freezes.

The polarization has produced a sharp increase in gridlock, bitterness, and delay. It is little wonder that the federal government, under pressure to deliver on promises that Congress and the president make, might hedge by retaining service contract employees as insurance. Experts may disagree about what has caused the polarization and associated uncertainty, but the resulting delays in legislative action on government budgets have created what the Partnership for Public Service has called a “government disservice”:

The end result has been a disservice to the American people, leaving federal agencies to cope with leadership vacuums that impede decision-making as well as funding uncertainties that disrupt services for the public, create inefficiencies, increase costs and make it difficult to plan and innovate. The current climate also has left federal leaders without constructive congressional partners to oversee their work or provide legislative authority to change or drop underperforming programs or embark on new initiatives. The partnership did not just take a stand against polarization but offered an aggressive reform agenda. It included a biennial budget and appropriations process, new oversight committees cochaired by members of the majority and minority, acceleration of the presidential appointments process, and rejection of across-the-board downsizing and budget cuts. In addition, it called out what it described as the “pervasive lack of understanding of and appreciation for the concerns of the executive branch among members of Congress and staff. …”

5. Deadly Adversaries

A proper blending of government and industry is impossible without creating effective controls against the troika of “cabal, intrigue, and corruption” that Alexander Hamilton called the “most deadly adversaries of republican government.”107 At least according to recent reports and investigations, all three appear to exist within the blended workforce, the only question being to what extent and effect.

Although most Americans do not know much about the blended workforce, they do know something about scandals. Their biggest complaint about their elected officials in Washington circa 2015 was special interest money and corruption (16 percent); a mix of lying, dishonesty, broken promises, and immorality (11 percent); being out of touch with regular Americans and caring only about their political careers (both 10 percent); not being able to work together (9 percent); violating the Constitution (4 percent); and a mix of being unqualified, bad managers, and idiots (3 percent). Cabal and intrigue did not show up in response to the Pew Research Center’s open-ended question, but their synonyms can be found on the list.

Gifts to presidential campaigns, favorite charities, and family brands are not the only adversaries of good government. So is the quiet fraud, waste, and abuse that has plagued government since Valley Forge. “Nepotism and favoritism were common means of awarding contracts,” writes procurement expert Sandy Keeney about the Revolutionary War. “Deliveries of spoiled meat, axes without heads, one-quarter size blankets, and shoes and saddles that fell apart were commonplace. Congress tried to eliminate fraud through regulation, but the resulting red tape was so burdensome and complex that it paralyzed the system.”

Fraud, waste, and abuse may be less flagrant today, but they are still easy to see in visible government breakdowns such as the Abramoff lobbying scandal in 2005, the failure to act against Bernard Madoff’s Ponzi scheme in 2008, the General Services Administration’s Las Vegas conference in 2010, Secret Service misconduct and ineptitude in the early 2010s, and the OPM hack in 2014.110 Fraud, waste, and abuse are also easy to tally in the government loan defaults, benefit overpayments, and uncollected fees, fines, and penalties that reached $138 billion in 2015, while the “net tax gap” of delinquent taxes was reported at $400 billion.

Some of the uncollected debt will eventually be collected, but the cabal, intrigue, and corruption that created the opportunities for error continue to take their toll on government performance. As last year’s debt falls, even more debt arrives, the total inventory climbs, and Congress and the president squeeze federal administrative systems and freeze federal employment to make up a fraction of the difference. Thus cabal, intrigue, and corruption create pressure to use contract and grant employees in lieu of federal employees based on convenience, even though some of their firms and agencies may well be creating the vicious cycle that weakens the administrative systems, funding, and capacity needed to draw the line between government and industry.

Options for Reform

Congress and the president are fully aware of the many pressures that might tip the blended workforce toward contract and grant reform. They have worked toward reform year after year, decade after decade, and have held one hearing after another promising reform. The result of this piecemeal effort has been inevitable: Congress and the president have made progress on many of the problems on the GAO’s high-risk list, but it keeps growing as other departments and agencies follow past practices.

There are still deep divisions along party lines on major reforms, especially given polarization. But there is also a growing realization that the federal government is broken. Contract firms justly complain about the federal hierarchy and paperwork burdens, grant agencies struggle to manage contracts under multiple layers of rules, and federal employee unions decry the understaffing highlighted throughout this paper.

If the goal is a comprehensive package designed to improve the performance of the blended workforce performance, reformers can start their bipartisan conversations by reading the final reports of Paul Volcker’s 1989 and 2003 reports on the state of the public service and his recent remarks on the state of the public service today:

"We depend on government in so many ways, often unseen and unrealized. But one can’t help but conclude upon seeing our institutions at work—or, more accurately, not working to their fullest potential—that we need to make some fixes. These institutions, from the UN and the World Bank, to our federal, state, and local governments for that matter—are tools that can improve people’s lives. We need them to run well. We have seen what happens when insufficient attention is given to understanding and mastering the basics of execution—the botched launch of healthcare.gov, the gaming of the veterans’ medical scheduling system, and, of course, the failure of the financial regulatory system to prevent unacceptable levels of private sector risk-taking at the expense of the stability of the economy."

Volcker’s two commissions did not discuss Washington’s blended workforce per se but focused on many of the pressures on the dividing line. They also offered comprehensive proposals for action. They believed that small-scale reforms would not be enough to produce the more effective government Americans would respect. Both commissions believed the time for tinkering was over and would be likely to reach the same conclusion again.