Sustainable State and Local Budgeting and Borrowing

The Critical Federal Role

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Even before Congress provided unprecedented financial aid to help offset the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was showering more than $1 trillion annually in grants and tax subsidies upon states and localities to help support America’s federal system. Yet Congress and the executive branch have demanded little in continuing, high-level oversight of states’ and localities’ budgeting and borrowing practices. This lack of oversight makes it difficult for federal authorities to help prevent fiscal crises that may end up costing the US economy and taxpayers tens of billions of dollars. In this issue paper, we examine why federal oversight of budgeting and borrowing is so limited and recommend steps Congress and regulators could take to bolster fiscal sustainability, improve transparency, and avert future fiscal crises at all levels of government.

INTRODUCTION

One Trillion Dollars.

That is the value of grants, tax exemptions, and tax credits that Congress provides annually to US state and local governments.

Four trillion dollars.

That is the size of the municipal bond market, the primary financing vehicle for almost 80 percent of the nation’s infrastructure spending. States and localities that raise funds in this market are the main beneficiaries of federal income tax exemptions on most municipal debt that will cost the US Treasury an estimated $382 billion in lost revenue over the coming decade.

Such are the financial ties that help bind America’s federal system of fifty sovereign states. The addition of trillions of dollars of aid to governments, companies, and individuals to offset the impact of COVID-19 has further raised federal investment in states and localities. Yet even amid this gusher of financial support, Congress and the executive branch have demanded surprisingly little in continuing, high-level oversight of states and local budgeting and borrowing. This lack of oversight makes it difficult for federal authorities to help avert fiscal crises that may cost the US economy and taxpayers tens of billions of dollars. In this issue paper, we examine why federal oversight of budgeting and borrowing is so limited and recommend steps Congress and regulators could take to bolster fiscal sustainability, increase transparency, and avert future fiscal crises in government at all levels.

Tightening oversight of state and local budgeting and borrowing are the cornerstones of the Volcker Alliance’s Richard Ravitch Public Finance Initiative. Ravitch is the former lieutenant governor of New York State and was a transformational actor in the federal bailout of New York City after its near bankruptcy in 1975. He was also a key player in the resolution of fiscal crises that ledto bankruptcies in Detroit in 2013 and Puerto Rico four years later.

Each of these crises was precipitated by governments borrowing excessively to support ongoing expenditures and maintain the fiction of balanced budgets. To this day, many governments continue to declare their annual or biennial budgets in balance—often in accordance with state statutes or constitutions—even though they have run up over $2.7 trillion in unfunded obligations for public worker pension and retirement health care costs, and another $1 trillion in deferred maintenance on roads, bridges, and other infrastructure. In the following pages, we argue that in return for trillions of dollars in federal funding and tax benefits, Congress should insist on two fundamental changes in its relationship with states and localities:

- State and local governments should be offered incentives to adopt generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) for budgets and the annual comprehensive financial reports (ACFRs) that largely follow these standards. GAAP requires recognition of promised payments when liabilities are incurred and discourage many onetime maneuvers—such as borrowing—to balance budgets.

- Federal lawmakers should take a more active role in overseeing the municipal securities market, which was largely deregulated in 1975.

Such changes may take years to achieve and will not be cost-free. Yet further discussion of—and act on on—these pressing issues is vital. It may be worth a considerable investment of time and money to ensure the stability of states, municipalities, and the US economy and prevent future fiscal crises.

A Six-Point Agenda for Discussion and Congressional and Regulatory Reforms

Budgeting

Set goals for sustainable state and local budgetary disclosure.

Require a credible estimate of how a budget will change a state or local government’s long-term liabilities.

Provide regulatory or statutory financial incentives for a transition to GAAP or modified accrual-based state and local budgeting.

Borrowing

Consider bringing state and local financial disclosure more in line with the type and frequency of information provided in the corporate market, as appropriate to issuers.

Weigh compelling states and localities to hew to common disclosure practices in ACFRs

Encourage voluntary cooperation with regulators by state and local governments, whether or not governments borrow in public capital markets.

BUDGETING: Pathways to Improvement

MOST STATE AND LOCAL GOVERNMENTS produce annual budgets that are balanced on a cash or modified cash basis. These require that cash receipts equal or exceed cash expenditures, with some exceptions made for revenues that will be received shortly after the fiscal year ends.

This method differs from the modified accrual-based system, used under GAAP, for financial reporting of governmental funds in ACFRs. In this system, revenues are recognized when they are measurable and available, and expenses when they create a claim on current financial resources.

These two accounting methods often produce divergent results because of differences in the way they recognize revenue and expenses. While a balanced state budget may suggest adequate, real-time fiscal health, it may not reflect accrued additional liabilities that pose substantial risks to future fiscal health. As a result, one of the most frequent criticisms of annual cash-based budgeting is its lack of transparency about the impact that budget decisions have on longer-term fiscal sustainability.

Annual cash budgeting allows governments to make short-term spending decisions without accounting for their medium-to-long-term implications, which opens the door for fiscally unsustainable tactics to achieve balance. Examples of such unsustainable maneuvers include borrowing for operational expenses, moving current-year expenditures to the following year, accelerating future revenues into the current year, selling assets, skipping pension contributions, and refinancing debt service to remove costs from the current year.

Though such moves may be politically expedient and yield short-term benefits, they are often costly in the long run and compromise fiscal health. Indeed, the Richard Ravitch Public Finance Initiative considers the resulting lack of transparency a violation of the promise government makes to citizens to provide a proper accounting of taxpayer funds and to maintain the delivery of services. The risks of such budgeting maneuvers accrue to various stakeholders. Government actors may be unable to assess how policies and decisions enacted in the moment will affect services going forward. Citizens and business owners may be disadvantaged by unanticipated tax increases. Municipal bond investors may find it difficult to assess the value of their holdings. When revenues lag, it is a relatively common practice to reduce contributions for public worker pensions or retiree health care. Recognition of and transparency about the future costs of short-term budgetary fixes are far more desirable than unpleasant surprises.

To bring more fiscal accountability to budgeting, one method advocated by municipal industry participants is that states and localities budget in accordance with GAAP.* Used by New York City after its near bankruptcy in 1975, the technique requires recognition of promised payments when liabilities are incurred and eliminates many one-time maneuvers to balance budgets. The method is already recommended by the Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB) for municipal financial statements, including ACFRs. GAAP underlies the annual budgetary assessments that the Volcker Alliance conducted in the five years before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in the US (see box).

While a GAAP-based budget can help stakeholders understand the full cost of government services, it is not without its own difficulties. Accrual-based budgeting is arguably more complex to implement and understand than a cash-based system. In addition, moving to an accrual-based system requires developing new standards, systems, and regulations, as well as funding for education and training. Transition would require valuation of capital assets, giving rise to questions regarding what to consider assets and how to effectively value them. Man foreign countries that have adopted a variation of accrual budgeting have limited its use to certain programs or functions while retaining cash-based budgets for others, thereby keeping the advantages of both. The US has some notable examples of governments—specifically those of New York City and the state of Connecticut—that have modified their budgeting processes to address some of the perceived shortcomings of cash-based budgeting:

- New York City In 1975, following the city’s financial crisis, the state legislature passed the New York State Financial Emergency Act for the City of New York (FEA).1 The system established under the FEA is often held up as a model of government fiscal practices. It subjects the city to oversight and requires it to maintain a balanced budget in accordance with its interpretation of GAAP, produce a four-year fiscal plan, and maintain certain reserves. In 2020, the FEA was amended to include provisions for a revenue stabilization fund, often called a rainy day fund.2 New York’s system has not eliminated the occasional use of fiscally unsound tactics to sustain spending and “balance” the city’s budget—including borrowing proceeds for operational expenses and asset sales. But it has dramatically improved transparency concerning the long-term impact of current-year budget decisions.

- Connecticut Because of an executive order 38 and legislation passed in 2011,4 Connecticut in 2014 began to shift its budget from a modified cash accounting method to a version of GAAP budgeting. It is also working toward eliminating the accumulated GAAP deficit in its financial statements. The state now uses the modified accrual system to balance its budget, and its surpluses are generally used to bolster reserve funds or reduce debt. Connecticut notes that the purpose of the current system is to ensure that its appropriated funds are managed in a way that remains balanced. Over the past several years, the state’s new budget system and strong oversight controls have led to a lower accumulated GAAP deficit, to enhanced reserves,5 and to improved credit ratings.6

* When referring to budgeting in accordance with GAAP, we mean adhering to the overarching principles established by the Governmental Accounting Standards Board for state and local financial statements.

The Volcker Alliance Principles of Sustainable Budgeting

The late Paul A. Volcker, the former Federal Reserve chairman and founder of the Volcker Alliance, observed in 2015 that fiscal pressures had encouraged many states to “shift current costs onto future generations and push off the need to make hard choices on spending priorities and revenue practices.” While trillions of dollars in federal pandemic aid to states, localities, companies, and individuals since 2020 left many governments with record budget surpluses by 2022, shifting the cost of current services to the next year or decade will remain a pressing concern once emergency federal aid wanes and more normal economic conditions return.

In response to Mr. Volcker’s observation, the Alliance has laid out a set of principles in five areas that are critical to governments’ ability to maintain budgetary balance for the long term and each year. The following list of principles is adapted from the 2021 report, Truth and Integrity in State Budgeting: Preparing for the Storm.7

- Budget forecasting States should adopt binding consensus estimates for revenues and make predictions about both revenues and expenditures for more than the next fiscal year. A one-year estimate does little to reveal structural deficits that may burden subsequent budgets. States should provide explanatory details to support forecasts of revenue growth.

- Budget maneuvers To avoid creating long-term structural deficits that burden future budgets, states should pay for expenditures with recurring revenues earned the same year. Budget maneuvers are states’ major tool for moving budgeted costs to the future or bringing expected revenues into the current year. By their very nature, such one-time actions may not be sustainable year to year, although some particularly challenged states, including Illinois, Kansas, New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania, consistently used maneuvers to balance budgets in the five fiscal years studied.

- Legacy costs To avoid creating long-term unfunded liabilities, states should consistently make contributions that actuaries recommend for public employee pensions and other postemployment benefits, principally health care.

- Reserve funds States should enact clear policies for rainy day fund deposits and withdrawals and adjust fund levels for the historical volatility of their revenues.

- Transparency States should provide the data that public officials and citizens need to understand budgets. These include online disclosure of budgetary information; public reporting of the scope and cost of tax expenditures, such as exemptions, credits, and abatements; and reporting of the cost of deferred infrastructure maintenance.

BORROWING: Increasing Transparency

STATE GOVERNMENTS, which determine how their local governments borrow money and account for their finances, have often tolerated poor transparency. While the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board (MSRB) have improved disclosure guidelines in recent years, oversight of state and local financial reporting has been limited. Perhaps because of the implicit political benefits of leaving well enough alone, Congress has been reluctant to mandate improvements to state and local financial disclosure practices, usually waiting for an emergency, a major default, or another systemic crisis of confidence in municipal governance before even considering action.

For example, while standardized disclosure of liabilities for public worker pensions and other postemployment benefits (OPEB), principally health care, are required of state and local bond issuers, their financial statements and disclosures provide little or no information on deferred infrastructure maintenance–related liabilities of at least $1 trillion. This undercuts governments’ fiscal sustainability and increases risks for municipal investors, taxpayers, and the US economy, if crises stemming from these poor disclosures are deep enough to require Congress to act.

In fact, full transparency has been inconsistent and inadequate in the market for municipal securities (figure 1). That is despite the MSRB’s creation in 2009 of Electronic Municipal Market Access (EMMA), an online clearinghouse for financial and other reporting by entities that borrow in the municipal market. While that market itself was created as a platform for subsidized financing of public infrastructure, neither Congress nor federal regulators have attempted to compel state and local borrowers to follow corporate standards of financial disclosure. As a result, municipal borrowers tend to move in and out of compliance with expectations to disclose material information to investors. Such a weak state and local government financial disclosure regime can hide and thus encourage imprudent or improper management choices that work to the detriment of reliable, long-term provision of services and sustained economic growth.

In fact, full transparency has been inconsistent and inadequate in the market for municipal securities (figure 1). That is despite the MSRB’s creation in 2009 of Electronic Municipal Market Access (EMMA), an online clearinghouse for financial and other reporting by entities that borrow in the municipal market. While that market itself was created as a platform for subsidized financing of public infrastructure, neither Congress nor federal regulators have attempted to compel state and local borrowers to follow corporate standards of financial disclosure. As a result, municipal borrowers tend to move in and out of compliance with expectations to disclose material information to investors. Such a weak state and local government financial disclosure regime can hide and thus encourage imprudent or improper management choices that work to the detriment of reliable, long-term provision of services and sustained economic growth.

Municipal bond investors have accepted governments’ poor disclosure practices partly because US issuers rarely default on their scheduled debt service payments. But investors are not the only stakeholders at risk from governments’ shortsighted decision-making. Taxpayers, service recipients, employees, and private sector employers are all vulnerable when government budgets require substantial corrections to be brought into balance. Citizens should have access to reliable information from which they can assess government’s ability to pro- vide adequate services at an affordable tax rate and over a long period of time.

Bond investors and other stakeholders criticize municipal borrower disclosure on a number of fronts. One of their most frequent concerns is slow or missing regular financial reports. But there are other and arguably more critical problems, including 250 incomplete disclosure.

These inadequacies stem from states’ inconsistent adherence to and application of national accounting rules for financial reporting. Reporting may be even less useful in states that follow state-specific standards or barely police which methods governments use.

In a similar way, the SEC’s protocols for municipal borrower disclosure rely on unevenly enforceable promises made in offering documents and on voluntary postings concerning material events that don’t require disclosure. Municipal borrowers are commonly advised by their attorneys that posting nonrequired information may invite future liability or subject them to recurring disclosure obligations. Disclosure lapses naturally accumulate among smaller or infrequent borrowers that have not committed sufficient institutional resources to transparency and among distressed municipalities that lack the resources as well as the incentive to report unattractive financial trends or reputationally damaging material events.

Municipal investors and other stakeholders have seen incremental improvements in disclosure since the 1929 stock market crash—improvements driven primarily by crises that might have been averted with a more robust disclosure regime.

Following the Great Depression, Congress acted to ensure that financial markets would be safe for investors and passed the Securities Act of 1933 (1933 Act).8 The intent was to increase transparency and protect against misrepresentations and fraud. The 1933 Act requires registration of all nonexempt securities with the SEC and disclosure of material information to allow investors to make informed decisions. The latter is accomplished through the filing of a prospectus or offering document. Whereas the 1933 Act covers the initial issuance of securities, the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (1934 Act)9 regulates securities in the secondary market and imposes ongoing disclosure requirements to ensure that investors have the information necessary to monitor their investments.

Congress exempted municipal securities from registration requirements under the 1933 Act. Justifications included investors’ institutional nature, the relative safety of the securities compared with corporate issuances, a perceived lack of fraud, and the need to uphold the principles of federalism and states’ rights as sovereigns under the US Constitution. Not- withstanding the registration exemption, municipal issuers are still subject to the antifraud provisions of the 1933 and 1934 Acts.

As individual investors increased their municipal bond holdings in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Congress passed the Securities Acts Amendments of 1975 (1975 Amendments).10 Around the same time, New York City’s financial crisis raised questions about whether investors and residents had been given inadequate or misleading information. The crisis led some in Congress to ask if it should reverse the registration and reporting exemptions granted to municipal bond issuers. The idea was scuttled for several reasons, including costs and the belief that reversing the exemptions was an outsize response.

Instead, the 1975 Amendments required the registration of municipal securities dealers, put them under the SEC’s rulemaking and enforcement authority, and created the MSRB, which is subject to the commission’s oversight. The MSRB was given the power to adopt rules for the municipal market. But under the Tower Amendments,† named after Republican Texas Senator John G. Tower, both the SEC and MSRB were prohibited from directly or indirectly requiring municipal issuers to make any filing or disclosure before or after the sale of securities. The SEC “requires underwriters of municipal securities offerings to obtain issuers’ disclosures for the securities they intend to sell and provide them to purchasers.”11

The limits on oversight and transparency were tested in 1983, when the Washington Public Power Supply System (WPPSS) defaulted on $2.25 billion in municipal bonds financing the construction of two nuclear power plants. The default was sparked by a state Supreme Court ruling that local governments lacked the authority to enter into “take-or-pay” agreements for power supplied by the utility.12 (Such contracts require buyers to purchase an agreed-on amount of a plant’s output, if produced, in a specified period.) In effect, the court’s ruling led to a market understanding that bondholders had been carrying much more of the risk of project performance than had been conveyed in offering and other presale documents.

In 1988, the SEC found the review and disclosure of WPPSS’s condition by the issuer, its underwriters, and bond counsel to be inadequate.13 As a result, the commission proposed Rule 15c2-12, enacted in 1989 and taking effect in 1990, which mandated that broker-dealers contract with municipal issuers when underwriting securities to receive preliminary and final official statements and ensure that investors had access to them before bond sales.

In a research document of remarkable foresight, the SEC Staff Report on the Municipal Securities Market14 expressed concern that state and local borrowers’ rising use of financial derivative instruments could pose undue risks to a market dominated by individual investors. The lack of continuing disclosure by municipal issuers compounded this problem, leading the SEC to support a bill requiring municipal issuers to provide initial and ongoing disclosure and annual reports. Absent such a law, the SEC wanted an amendment to Rule 15c2-12 to prohibit “municipal securities dealers from recommending outstanding municipal securities unless the municipal issuer makes available ongoing information regarding the financial condition of the issuer of the type required in initial offerings.”

The SEC’s requested revision was adopted in November 1994, just days before Orange County in Southern California disclosed that it had lost $1.5 billion of its $7.5 billion investment pool by engaging in an aggressive strategy that involved $12.5 billion in borrowings to purchase derivatives and structured notes.15 The county was forced to file for bankruptcy when the fund and the investment strategy blew up as interest rates rose that year. The bankruptcy brought into focus how little the county had disclosed to the public about its investments. “So unaware were local officials of the mounting losses that in June four education authorities with money in the fund—the Orange County Board of Education, the Irvine Unified School District, the Newport-Mesa Unified School District and the North Orange County Community College District—borrowed a total of $200 million solely to invest in the funds,” the New York Times reported.16

The financial crisis and recession of 2007–09 collapsed large segments of the municipal bond market. These included the bond insurance industry, which at the time guaranteed repayment on more than half of all outstanding municipal bonds—nearly all of them rated investment grade. Also compromised were the auction rate securities market, the tender option bond market (where investors used leverage to gain outsize returns on regular municipal securities), and the variable-rate demand obligations (VRDO) market (in which long-term debt bearing short-term interest rates was issued.) The financial crisis also accelerated the descent of Jefferson County, Alabama, into bankruptcy in 2011.

In 2010, the SEC expanded Rule 15c2-12 to include all so-called demand securities (like VRDOs) in its provisions; shorten the time frame in which issuers must post notices of special events; add other event notices, such as filing for bankruptcy, to required disclosures; and remove considerations of materiality for the most important event filings, including payment defaults, unscheduled draws on reserves or bond insurance, defeasances, and rating changes.17

The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act18 of 2010 required the SEC to conduct a detailed study of the municipal market and related issuers’ disclosures. which was published in 2012.19 While the SEC did not suggest repealing the Tower Amendments, it did recommend that Congress

- direct the SEC to require municipal borrowers to disclose pre- and post-sale financial information in standardized terms;

- extend registration requirements to nongovernmental borrowing entities;

- establish the form and content of financial statements;

- require that disclosed financial reports be audited; and

- provide a mechanism to enforce compliance with continuing disclosure agreements and a safe harbor from private liability for forward-looking statements by municipal borrowers.

Even with Detroit’s 2013 bankruptcy filing and subsequent payment defaults, Congress did not adopt any of these changes, perhaps because the city’s long-running economic challenges had been well chronicled in the media and in its own financial disclosures.

The SEC amended 15c2-12 in 2018 in response to industry concerns over potential state and local credit problems lurking in poorly disclosed direct loans by banks.20 After the financial crisis changed banks’ accounting of contingent risks, thus dampening profits from guaran- tees on VRDOs, banks had begun lending cash directly to municipal governments. Aggregate direct loans from banks to municipal borrowers more than doubled, peaking at $190 billion in 2018. Related SEC amendments added new disclosure requirements for borrowers, including financial obligations and defaults or modifications on such obligations that reflected financial difficulties of the issuer.

Although the registration requirements under the 1933 Act are not applicable to municipal securities, its antifraud provisions under Section 17(a) are, as are those under Section 10(b)

of the 1934 Act and the SEC’s Rule 10b-5. Under these acts, it is unlawful to use any method to defraud or to engage in a transaction that operates to defraud or deceive a purchaser of securities in the primary or secondary markets. Rule 10b-5, which was adopted by the SEC in 1942 to implement Section 10(b), prohibits misstatement or omission of material facts in the offer, purchase, or sale of securities.

The SEC’s use of a so-called ex post enforcement mechanism—like investigating a Rule 10b-5 violation—has limitations and implications, including

- failure to provide clear guidance up front on disclosure expectations;

- taxpayer litigation costs and any penalties assessed on the government;

- higher borrowing costs or lack of market access due to concern over the SEC investigation or reasons behind it; and

- the risk that the threat of penalties for misstatements might deter qualified applicants from seeking employment in public service.

Without other tools to compel adequate disclosure in the municipal market, however, the SEC has used its enforcement mechanism under the antifraud provisions of the 1933 and 1934 Acts to effectively communicate disclosure expectations and shape the behavior of mar- ket participants. SEC enforcement actions under Rule 10b-5 can be directed at a particular situation or as part of a broader enforcement sweep.

Failure of several municipal issuers, including San Diego, and of the states of Illinois, Kansas, and New Jersey to disclose in bond documents material information about the health of their pension systems led to SEC administrative proceedings and enforcement actions that included cease and desist orders and required remedial action. Because of heightened awareness that the SEC considered opaque or missing pension information to be a material misrepresentation or omission, industry participants and GASB undertook several projects that have greatly improved the transparency concerning pension systems’ impact on the host government’s fiscal position.

Perceiving widespread noncompliance with Rule 15c2-12, the SEC implemented a larger and more aggressive action to compel issuers and underwriters to improve disclosure. The Municipalities Continuing Disclosure Cooperation Initiative was the largest mass enforcement of the rule and allowed self-reporting of compliance lapses by Dec. 1, 2014; the lapses were to be resolved with predetermined penalties.21 As a result, seventy-two broker-dealers representing 96 percent of municipal underwriting and seventy-one municipal issuers were subjects of enforcement actions. Violators who did not self-report faced harsher penalties later. The SEC’s message was clear: Compliance with 15c2-12 is to be taken seriously. Indeed, municipal disclosure filings rose by 18 percent in the final year of the initiative.

An obvious solution to inadequate disclosure is that investors should simply demand more. But this has not happened; in fact, municipal investors’ calls for better dissemination of fundamental credit information have subsided in recent years. This reflects several factors.

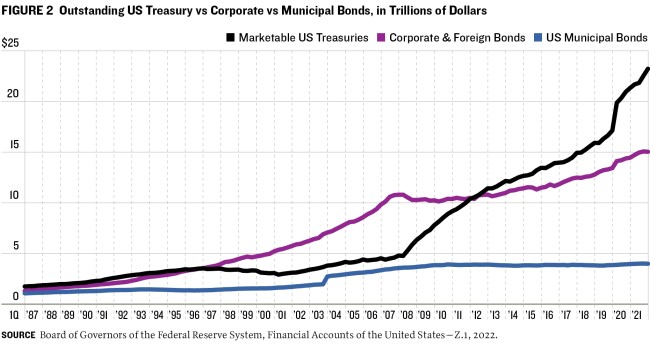

First, most traditional US municipal bonds are unique in that they provide income that is exempt from federal as well as most states’ income taxes. This means that an investment portfolio created to generate tax-exempt income must remain fully invested in tax-exempt municipal bonds, regardless of current or future interest rates, credit quality trends, or the adequacy of financial disclosure. But the outstanding universe of tax-exempt bonds available to investors has been limited as the austerity of states and localities has extended to their investment in infrastructure. Figure 2 highlights that while the outstanding face amount of marketable US Treasury securities has increased 495 percent, the face value of the entire municipal bond universe is up just 12 percent. In addition, a rising share of the outstanding municipal market has been filled by issuance of taxable rather than tax-exempt securities. As a result, the total dollar amount of outstanding tax-exempt municipal bonds may have declined in absolute terms in this period.

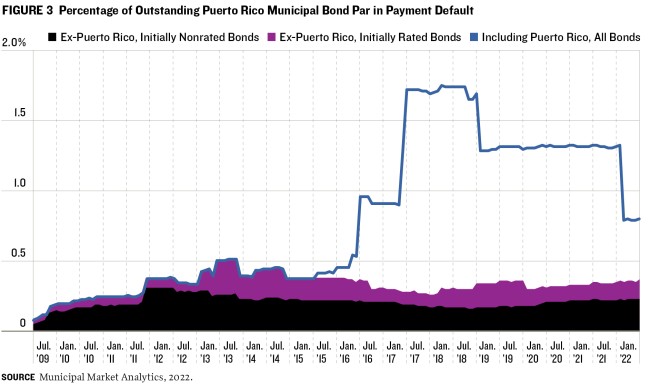

It is improbable that, when dealing with such a scarce resource as tax-exempt municipal bonds, investors have much discretion over whether to buy or hold a specific security based on a borrower’s disclosure practice. This is particularly true when the vast majority of municipal bonds remain distant from any kind of monetary or technical default. Figure 3 illustrates just how rare such defaults are. Including the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic but excluding Puerto Rico, which entered a form of bankruptcy after Congress passed the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA)22 in 2016, less than 0.4 percent of the outstanding $4.1 trillion of municipal bonds was in payment default as of Oct. 1, 2022. The municipal default rate peaked at 1.8 percent in 2017. That Included Puerto Rico, a chronically weak and late discloser of financial information despite having debt of over $72 billion and $55 billion in unfunded pension liabilities when PROMESA was enacted. As of July 2022, only 0.01 percent of all outstanding debt, including rated and non- rated bonds, in the largest municipal bond sector—the roughly $1.2 trillion in state and local general obligation bonds—was in payment default.

Finally, other changes in the municipal market have further limited investors’ direct expo- sure to idiosyncratic credit risk, allowing them to disregard late or faulty financial reporting. These include the transition to low-cost “passive” investing strategies, including exchange- traded mutual funds. In such instruments, the investment manager does not actively undertake credit analysis on each security considered but instead selects bonds based on their inclusion in an independently maintained index that itself partly depends on publicly available credit ratings. At the same time, more institutional investors are using nontraditional sources of information, such as computer-driven extraction of data from government and third-party websites, to approximate a municipal borrower’s credit condition and to augment the data offered by a more traditional credit review of audited financial results.

A recent study by Christine Cuny, an associate professor of accounting at New York University’s Leonard N. Stern School of Business, found that political motivations can at times outweigh the potential capital market benefits of transparency.23 The potential for individuals or political parties to influence the flow of information to investors and the electorate undermines the ability of a voluntary disclosure system to fully succeed.

Politicians who govern municipalities facing fiscal or economic deterioration are some- times more concerned about the impact the release of the information will have on their reelection than about the potential cost in the capital market of nondisclosure. “Disclosure may decline because self-interested politicians seek to maximize their own utility,” Cuny argues.26 “One way to maximize utility (increase the probability of re-election) is to temporarily suppress information that may be reputationally damaging.” This is more likely to be the case when municipalities are infrequent debt issuers. The 2007–09 financial crisis provides an example of disclosure trends during a period when negative information was plentiful. Disclosure compliance rates declined from 67 percent before the crisis to 60 percent during it, according to a 2011 study by DPC Data.27

The Cuny study examined 1,972 bond issues for 1,359 unique issuers in forty-eight states. It found that during the period studied (2004–12), 71 percent of the issuers released financial statements in an average year.28 The average time to release financial statements was seven months after the end of the fiscal year. It was found that annual financials were far more likely than budgets to be filed on EMMA (or with a pre-EMMA repository).

Issuers in counties that faced a negative change in their per capita personal income filed 7 percent fewer financial statements and were 33 percent less likely than other issuers to file an approved budget in the year following the income decline. Issuers that increased spend- ing were 4 percent less likely to file financial statements, released 11 percent fewer financial statements, and were 22 percent less likely to file an approved budget than issuers that didn’t raise spending levels.

There are several prominent examples in which fiscally distressed municipalities curtailed the release of information to the public. They include Puerto Rico, Detroit, and Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, the financially stressed state capital that was placed under state fiscal oversight in 2010 and attempted unsuccessfully to file for bankruptcy the following year. In these situations, the decisions regarding what financial information to disclose and when to disclose it publicly probably were probably complicated by the reputational risks to those in charge.

In one area, however, transparency improved notably. Cuny found that issuers of insured bonds increased disclosures after the bond insurance industry imploded to mitigate uncertainty regarding the credit quality of their debt. This most likely reflected issuers’ recognition that transparency does have benefits.

† 15 U.S.C. § 78o-4(d)(1) and (2).

A NEW ERA FOR DIGITAL STATE AND LOCAL FINANCIAL REPORTING?

The Financial Data Transparency Act of 2022 (FDTA),24 signed into law December 22, represents a significant change in federal involvement in state and local government borrowing activities, which were generally believed to be off-limits since the passage of the Tower Amendments in 1975. The amendments restricted the SEC and the MSRB from directly or indirectly requiring municipal bond issuers to make any filing or disclosure before or after the sale of securities. Under the FDTA, the SEC was given two years to develop data standards for information that municipal bond issuers provide to the MSRB, including that it should be machine readable. The statute also ordered the agency to adopt the standards within four years and allowed it to consider the needs of smaller issuers to “reduce any unjustified burden” on them.25 The FDTA is also notable for areas it does not address, including the quality and timeliness of financial disclosures by the public sector. While the act might pave the way for additional federal disclosure requirements for municipal bond issuers and test the bounds of—or even effectively eliminate—the Tower Amendments, it does not enhance disclosure requirements on the future costs of maneuvers that states and localities may employ to balance current budgets.

CONCLUSION: A Six-Point Agenda for Discussion and Action

Shortcomings in state and local financial transparency stem in no small measure from the structure of the federal system. By ceding authority to states, the US government has limited its role in creating and maintaining the municipal bond market and in oversee- ing state and local budgeting and financial accounting. It thus comes as little surprise that states and related stakeholders have strongly opposed efforts to reverse this history. Reform proposals have included marshaling congressional or regulatory authority to impose a single, rigid accounting standard in states and municipalities; undoing congressional prohibitions on pre- and post-bond issuance disclosures by state and local borrowers; and limiting bor- rower access to the federal income tax exemption on interest on state and local bonds for failure to follow such reforms.

Even so, improvement is not impossible. Almost five decades after its near bankruptcy, New York City’s embrace of GAAP for budgeting has obliged the city to produce transparent financial accounts and has helped it avert fiscal crises—often caused by borrowing to cover continuing expenditures—that many other cities and states have faced.

Industry and government groups, including the National Federation of Municipal Ana- lysts, credit rating agencies, and the Government Finance Officers Association, have all worked to improve disclosure mandates and guidelines. After the 2007–09 financial crisis, the demand for better accounting of unfunded pension liabilities from academics, policy advocates, and credit analysts ultimately drove the GASB’s accounting standards to change and led to the inclusion of pension data (and accompanying analyses) on state and local governments’ balance sheets and in other financial reporting disclosures. More recently, S&P Global Ratings research on the lack of disclosure of banks’ direct loans to municipal borrowers has resulted in inclusion of the loans in event notices required to be disclosed to investors under Rule 15c2-12. The municipal investors have begun on their own to incorporate in their analyses certain long-term risk and impact metrics related to environmental and climate change, social issues, and governance issues. Under pressure from investors, some state and local issuers will begin to provide their own forms of this information as well.

Still, state and local governments’ financial disclosures are mostly a look in a rearview mirror. The implications of current-year budget choices are often at best misunderstood and at worst ignored for short-term benefit. Informed decision-making is compromised to the detriment of all stakeholders. Based on the historical examples and current practices cited in this issue paper, we recommend further discussion and consideration by legislators and regulators of this six-point agenda:

BUDGETING

- Set goals for sustainable state and local budgetary disclosure. A budgeting system should be balanced annually or biennially, along the principles advocated by the Volcker Alliance (callout box 2). It should provide context on future revenues and spending, and describe the fiscal impact of budget decisions on the medium-to-longer-term health of the government’s balance sheet.

- Require a credible estimate of how the budget will change a state or local government’s long-term liabilities. For example, to the extent the budget entails enhanced employee benefits, this estimate would include any related increases in employer contributions to public worker pension funds, as well as changes in governments long-term unfunded liabilities. If the latest budget includes a new infrastructure spending program, this estimate should show the likely effects on total infrastructure assets and liabilities, including any reduction or increase in deferred maintenance costs.

- Provide regulatory or statutory financial incentives for a transition to GAAP or modi- fied accrual-based state and local budgeting. When presented with the disclosure of their budgets’ direct impact on public liabilities (and thus taxpayer costs), government managers may feel compelled to reduce, offset, or better justify any long-term costs to be accrued because of current policy choices. The goal would be to indicate how the current year’s budget and financial results reasonably affect the size and shape of that government’s long-term liabilities. The form of this indication might be left to the state or local government, as long as the content is meaningful—reasonably useful to investors and citizens, in other words. Qualitative and quantitative presentations, using written or numerical description, would be allowed. To encourage participation, the SEC might provide participating municipal bond issuers that disclose good faith estimates a clear safe harbor from related fraud litigation, regardless of the ultimate accuracy of those estimates.

BORROWING

- Consider bringing state and local financial disclosure more in line with corporate reporting standards. While the municipal market itself was created as a platform for subsidized public infrastructure financing, neither Congress nor federal regulators have attempted to compel state and local borrowers to follow corporate financial disclosure standards. As a result, municipal borrowers tend to move in and out of compliance with expectations to disclose material information to investors. Such a weak state and local government financial disclosure regime can hide and thus encourage imprudent or improper management choices that work to the detriment of reliable, long-term provision of service and thus sustained economic growth.

- Weigh compelling states and localities to hew to common disclosure practices in ACFRs. This may not be possible without eliminating the Tower Amendments. Even in the case of a fully empowered federal regulator with the authority to demand enhanced and fully digital state and local financial reporting, implementing best practices would involve lengthy and detailed negotiations with all stakeholders, including state and local governments, to maximize the quality of the data provided. If state and local governments opted for voluntary cooperation with adjustments to national accounting procedures, GASB might enhance its standards to include projections of financial or environmental risks. Adopting such a process would be deliberate and prolonged but could ultimately lead to extensive state and local government participation. In past years, GASB faced strong opposition from state and local borrowers when it attempted to incorporate explicitly forward-looking elements into its accounting standards. Any new program would need detailed negotiations to ensure that the costs and potential legal liabilities involved in publishing such information are not an onerous burden on state and local governments.

- Encourage voluntary cooperation with regulators by state and local governments, whether or not they borrow in public capital markets. Increasing the transparency of changes in near-term governance costs in the context of climate change, for example, should not be limited to the one-third of local governments that finance infrastructure development via the municipal market. For voluntary participants, material, predict- able, and persistent financial compensation for these efforts would be required. Governments might require a stream of federal grant money to carry out these tasks. If Congress fails to appropriate sufficient funds for the subsidy, state and local borrowers could decide whether to pay for the enhanced disclosure on their own. But a federal subsidy would not be unproductive. In coming years, climate change will only increase federal costs to improve and repair state and local infrastructure and economies. Federal incentives might entail cash or tax credits to help states and localities hire engineers, accountants, and analysts to understand or avert climate-related vulnerabilities—for example, lowering the costs of post-disaster remediation. Such incentives would also bolster the technical skills of US workers.

These recommendations should be regarded as a starting point. The roots of the federal government’s relatively hands-off policy date back not only to the 1970s, in the case of bond market regulation, but to the very foundations of the US as a collection of sovereign yet deeply interrelated states. In this environment, positive change has come incrementally and sometimes only when a fiscal or financial crisis looms. But an agenda for change should begin here.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This report was made possible with generous support from Volcker Alliance director Richard Ravitch and the Volcker Family Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors. We acknowledge the considerable support provided by the late Paul A. Volcker, the Volcker Alliance’s founding chairman, as well as the numerous academics, government officials, and public finance professionals who have guided the Alliance’s research on state budgets for the last seven years.

ENDNOTES

- New York State, New York State Financial Emergency Act for the City of New York, § 2 of Chapter 868 of the Laws of 1975, link.

- New York State Senate, Senate Bill S8400, 2019–20 legislative session, link.

- State of Connecticut, Executive Order No. 1, Jan. 5, 2011, link.

- Connecticut House of Representatives, An Act Implementing Provisions of the Budget Concerning General Government, House Bill 665, Public Act 11-48, July 2011, link.

- Keith M. Phaneuf, “Connecticut’s Coffers Continue to Swell, Despite Global Economic Woes,” Connecticut Mirror, Nov. 11, 2022, link.

- State of Connecticut (website), “Governor Lamont Announces Connecticut Receives Credit Rating Increase from S&P,” press release, Nov. 21, 2022, link.

- The Volcker Alliance, Truth and Integrity in State Budgeting: Preparing for the Storm, 2021, link.

- Securities Act of 1933, 15 U.S.C. § 77a (1933), link.

- Securities Act of 1934, 15 U.S.C. § 78a (1934), link.

- An Act to Amend the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, Pub. L. No. 94-29 (1975), link.

- Commissioner Luis A. Aguilar, US Securities and Exchange Commission, Statement on Making the Municipal Securities Market More Transparent, Liquid, and Fair, Feb. 13, 2015, link.

- Chemical Bank v. Washington Public Power Supply System, 102 Wash. 2d 874 (1984), link.

- US Securities and Exchange Commission, The Division of Enforcement Staff Report on the Investigation in the Matter of Transactions in Washington Public Power Supply System Securities, September 1988, link.

- US Securities and Exchange Commission, The Division of Market Regulations, Staff Report on the Municipal Securities Market, September 1993, link.

- Mark Platte and Debora Vrana, “Orange County’s Fund Value Falls $1.5 Billion: Officials Seek to Calm 180 Cities and Agencies and Prevent Run on Once High-Flying Portfolio,” Los Angeles Times, Dec. 2, 1994, link.

- Floyd Norris, “Orange County’s Bankruptcy: Orange County Crisis Jolts Bond Market,” New York Times, Dec. 8, 1994, link.

- Amendment to Municipal Securities Disclosure, “Amendment to Municipal Securities Disclosure; Final Rule,” Federal Register 75, no. 111 (June 10, 2010), link.

- Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, Pub. L. No. 111-203 (2010), link.

- US Securities and Exchange Commission, Report on the Municipal Securities Market, July 31, 2012, link.

- Amendments to Municipal Securities Disclosure, “Amendment to Municipal Securities Disclosure; Final Rule,” Federal Register 83, no. 170 (Aug. 31, 2018), link.

- US Securities and Exchange Commission,“SEC Charges 71 Municipal Issuers in Muni Bond Disclosure Initiative,” press release, August 2016, link.

- Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act, 48 U.S.C. § 20 (2016), link.

- Christine Cuny, “Voluntary Disclosure Incentives: Evidence from the Municipal Bond Market,” Journal of Accounting and Economics 62 (2016): 87–102, link.

- James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023, H.R.7776 (2022), link.

- Inhofe Defense Authorization Act, 1033.

- Christine Cuny, “Voluntary Disclosure Incentives: Evidence from the Municipal Bond Market,” Journal of Accounting and Economics 62 (2016): 87–102, link.

- DPC Data, Recent Trends in Continuing Disclosure Activities, Feb. 3, 2021.

- Christine Cuny, “Voluntary Disclosure Incentives: Evidence from the Municipal Bond Market,” Journal of Accounting and Economics 62 (2016): 87–102, link.

© 2023 VOLCKER ALLIANCE INC.

Published January, 2023

The Volcker Alliance Inc. hereby grants a worldwide, royalty-free, non-sublicensable, non-exclusive license to download and distribute the Volcker Alliance paper titled Sustainable State and Local Budgeting and Borrowing: The Critical Federal Role (the “Paper”) for non-commercial purposes only, provided that the Paper’s copyright notice and this legend are included on all copies.

This paper was published by the Volcker Alliance as part of the Richard Ravitch Public Finance Initiative. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Volcker Alliance. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Don Besom, art director; Michele Arboit, copy editor; Stephen Kleege, editor.