Evaluating $1 Trillion in State Tax Expenditures

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

TO ADVANCE IMPORTANT POLICY GOALS, such as aiding low-income families or spurring business investment and job creation, states, like the federal government, frequently offer tax incentives to businesses and individuals. Known broadly as tax expenditures, these exemptions, credits, abatements, and other measures reduce state revenues by an estimated $1 trillion a year, almost three times their 2021 total expenditures on education.1

Tax expenditures are a less transparent form of spending scarce public resources than appropriations of cash and are often not subject to the same rigorous review. The absence of routine, critical evaluation means that tax breaks can persist unchecked for multiple budget cycles or longer.

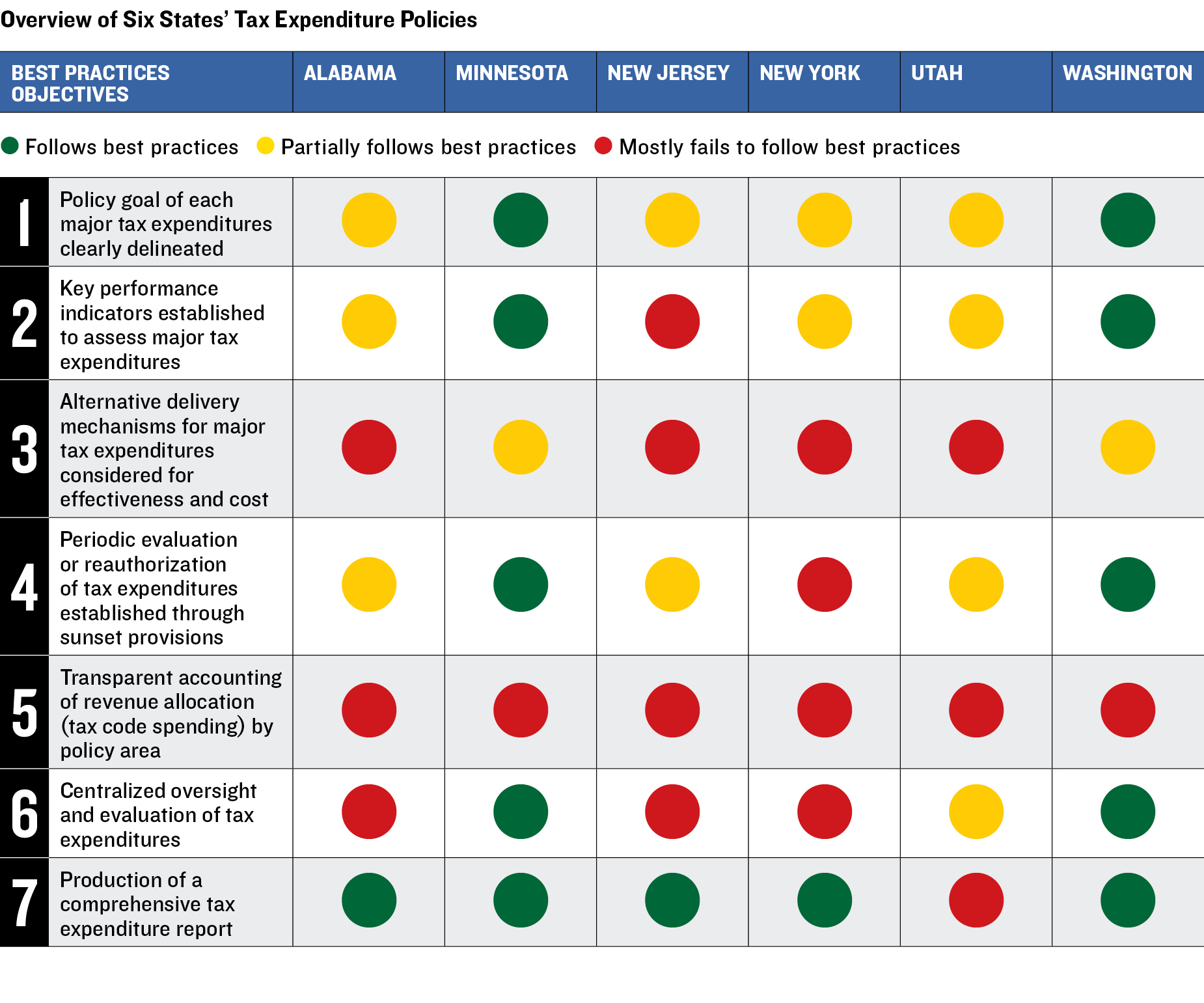

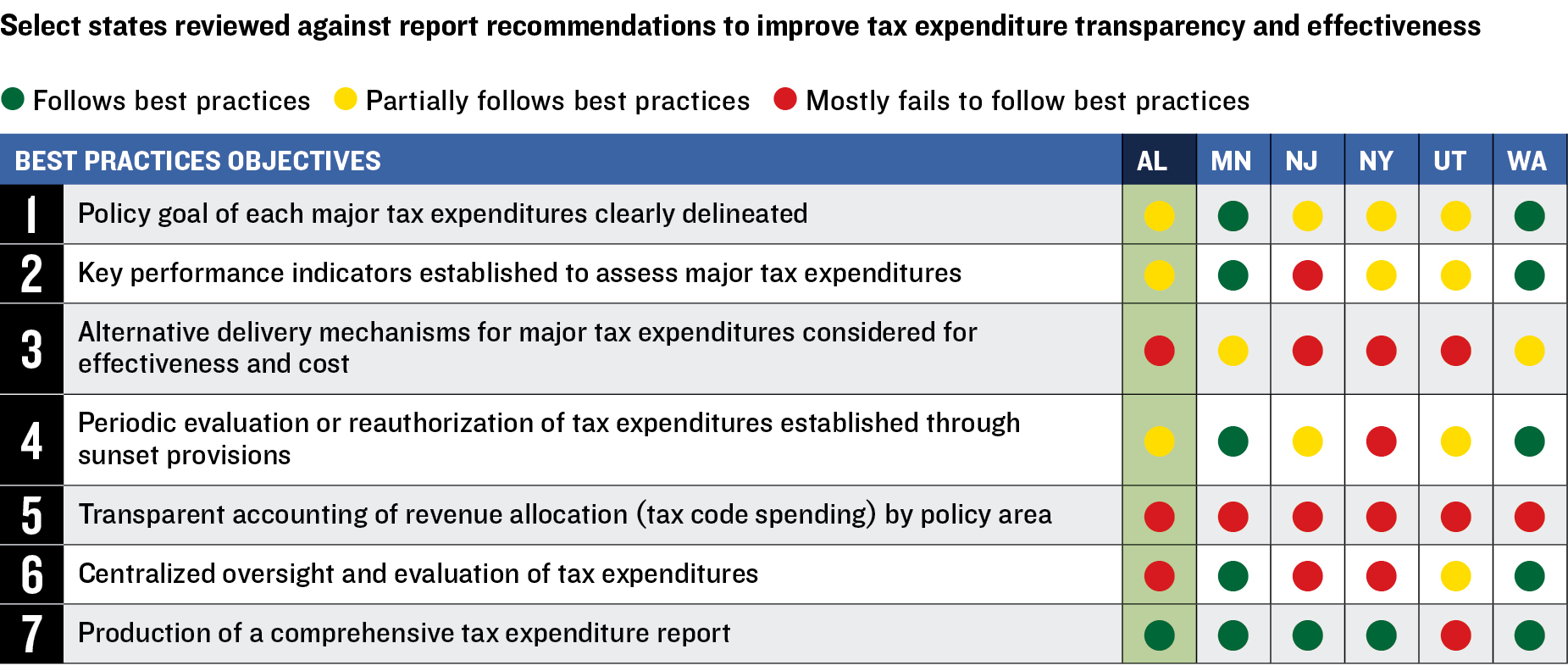

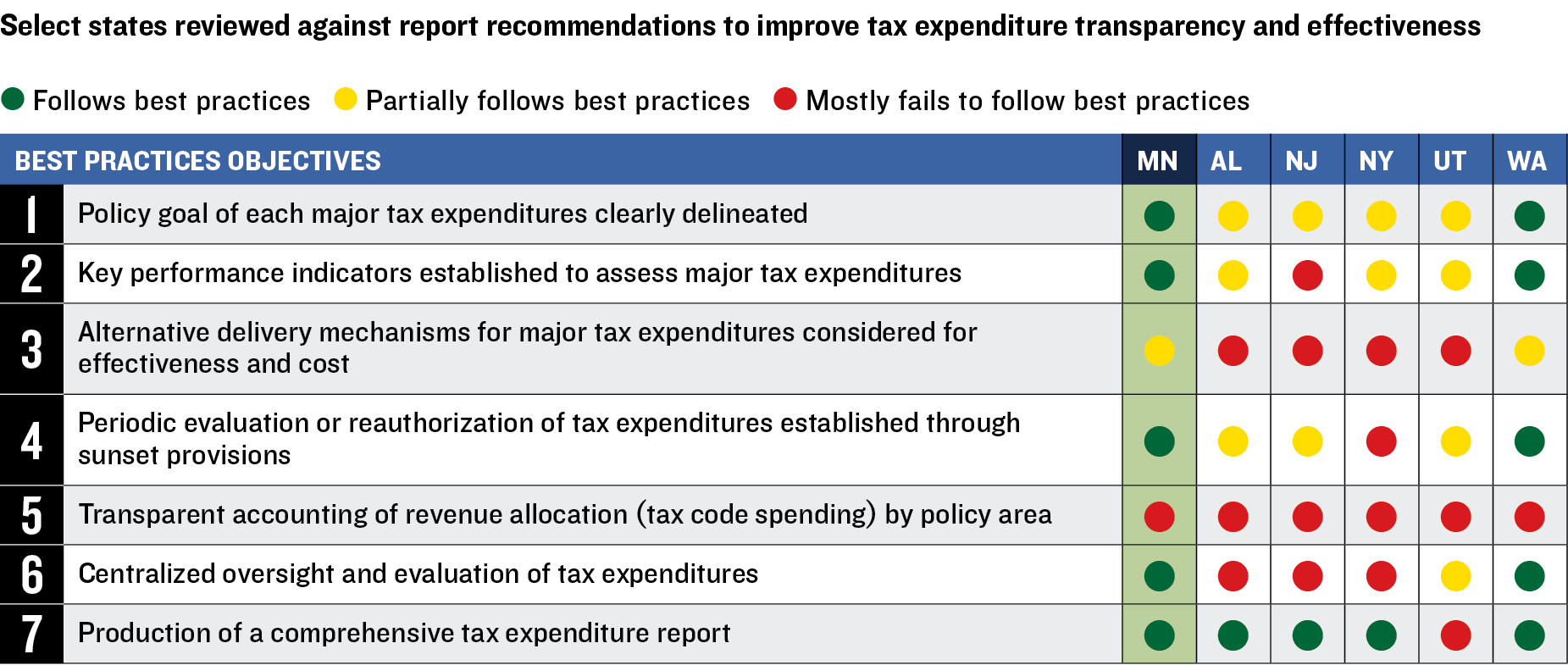

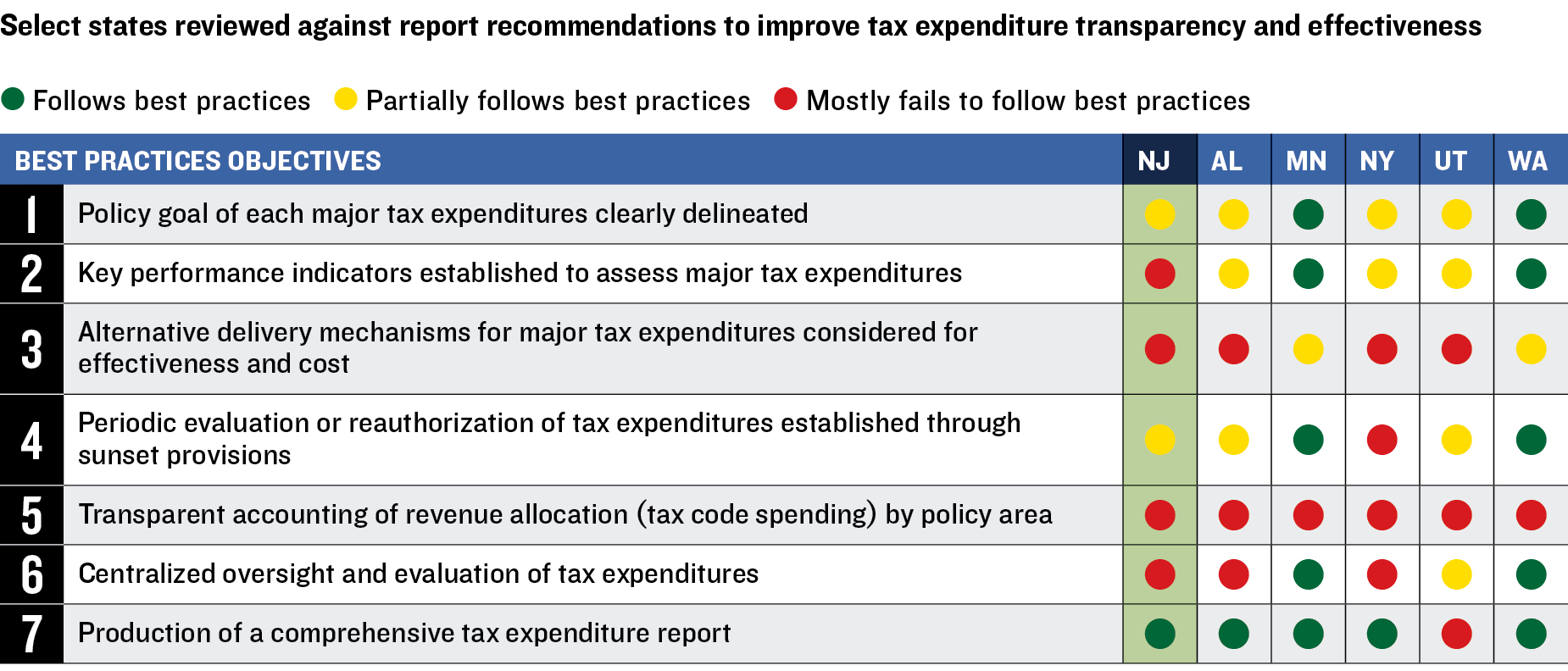

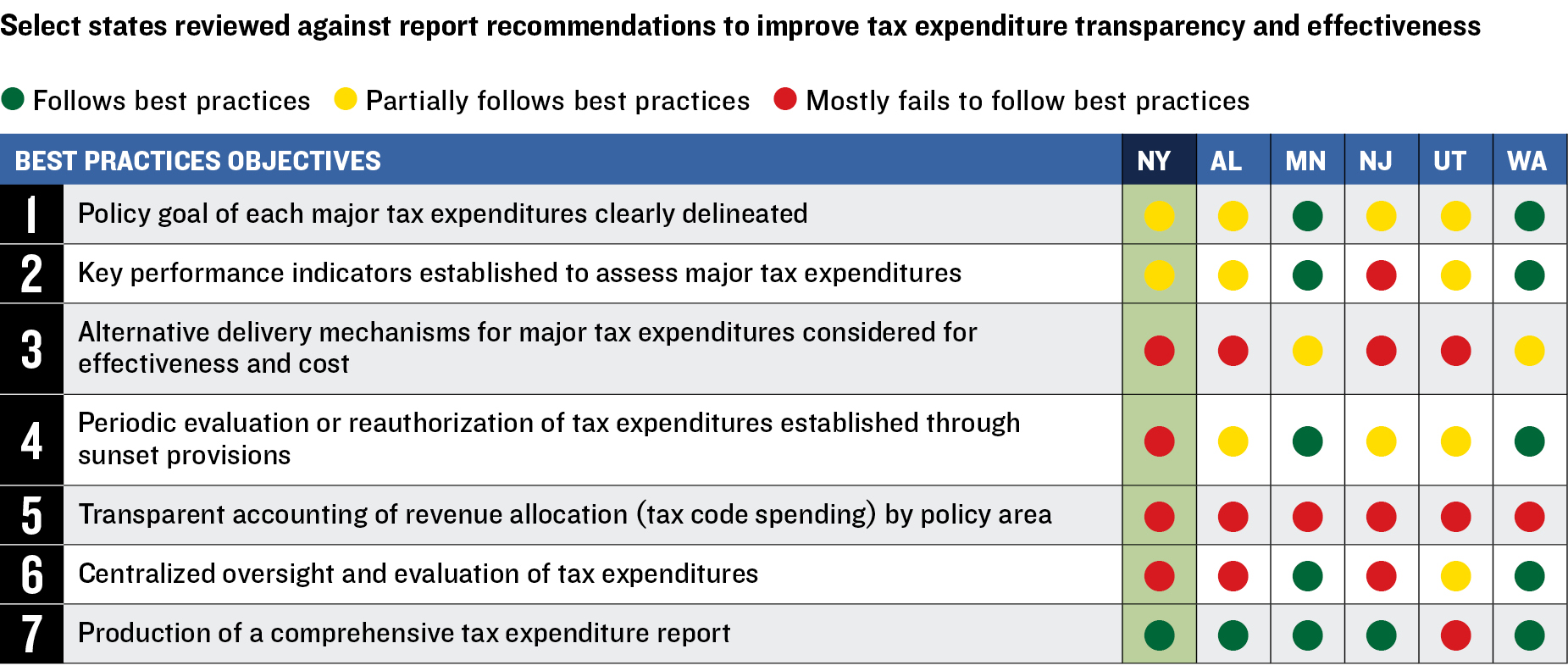

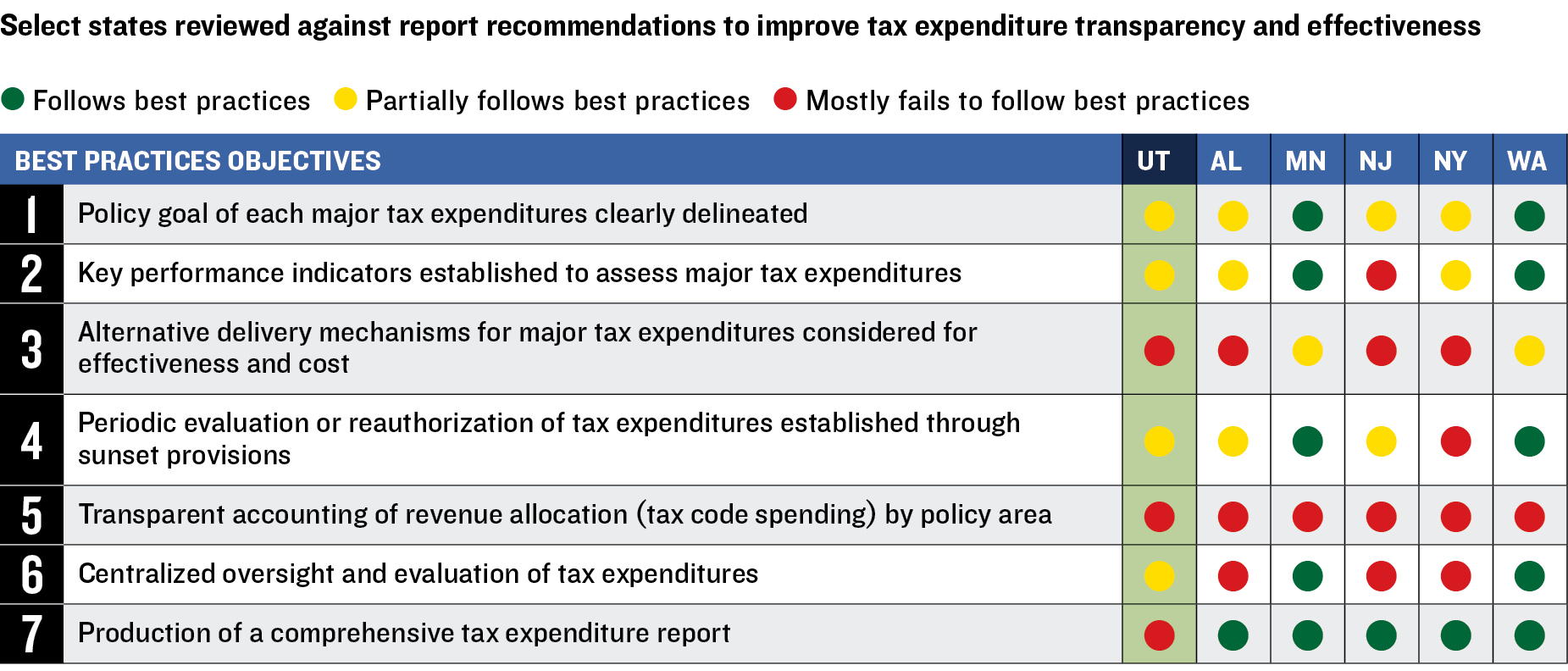

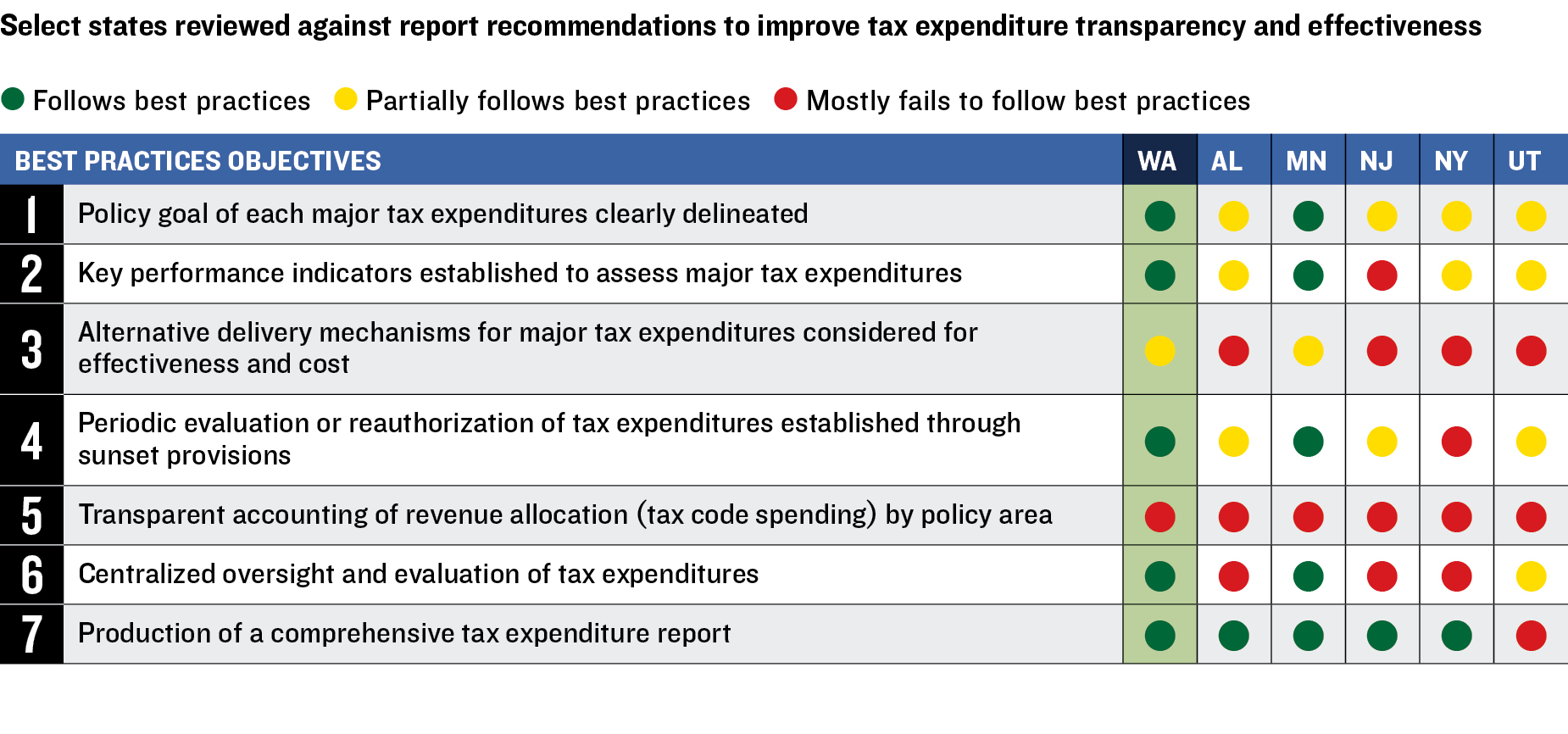

In this issue paper, we describe the different types of tax expenditures used by states and how they are disclosed, if at all. To show the wide variations in tax expenditure oversight and disclosure, we offer report cards comparing practices followed by six states with widely differing policies: Alabama, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, Utah, and Washington. We also offer recommendations for states to improve evaluation and disclosure of tax expenditures:

• Clearly delineate the policy and political reasons for major tax expenditures and consider the cost and reasonable effectiveness of policy alternatives, including direct spending to achieve similar goals;

• Create key performance indicators to evaluate every major tax expenditure to help gauge whether tax policies are satisfying original or amended objectives;

• Set standard sunsetting provisions for every tax expenditure and periodically assess those that relate to mirroring tax expenditures built into the federal tax code;

• Produce a resource allocation budget that reports direct spending and tax expenditure estimates by budget category; and

• Deploy professional staff and administrative resources to analyze and track tax expenditures.

INTRODUCTION

ADDRESSING THE TRILLIONS OF DOLLARS in needed spending to respond to the effects of extreme weather events and the cost of deferred maintenance means that states will substantially spend more on infrastructure now and in the decades ahead. Given these budgetary pressures, states should take a critical eye to tax incentives, exemptions, abatements, and deductions—together called “tax expenditures.” Such expenditures reduce states’ revenues by approximately $1 trillion per year.2 The annual costs of tax expenditures far exceed the $346 billion spent on education and is almost ten times greater than outlays for highways in 2021.3 Indeed, total state tax collections could be about 50 percent higher under current tax rates, were it not for tax expenditures.

While some tax expenditures advance important policy goals—such as aiding low-income families or spurring business investment and job creation—others may not. But states appear to spend little time assessing the difference. And, while some states make a full and transparent accounting of their tax expenditure programs, others provide little transparency.

USING TAX EXPENDITURES TO ACHIEVE POLICY GOALS

STATES OFTEN USE TAX EXPENDITURES to supplement direct spending to achieve a range of policy objectives. The following examples demonstrate how specific tax preferences are applied:

PROVIDING INCOME SUPPORT Minnesota’s Working Family Credit provides a refundable tax credit for individuals who qualify for the federal earned income tax credit. The purpose of the state credit is to encourage work and to raise income levels above the poverty level.

MAKING ESSENTIAL PURCHASES MORE AFFORDABLE Florida’s exemption from sales taxes of groceries purchased for human consumption is intended to ease a financial burden on residents with limited incomes.

ENCOURAGING AFFORDABLE HOUSING CONSTRUCTION Under New York State’s Low Income Housing Credit, the state provides a ten-year tax credit to investors in qualified low-income housing that meet certain criteria.

FOSTERING ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT Minnesota’s Research and Development Credit allows entities conducting research and development to claim a nonrefundable tax credit against corporate franchise or individual income taxes. Typically, 50 percent of current-year allowable expenses are eligible for this credit, which is intended to create or retain jobs and companies in the state.

PREVENTING “TAX PYRAMIDING” New Jersey’s exemption of purchases intended for resale from the sales tax provides an exemption on goods acquired for retail sale or acquired by manufacturers to finish. Only the finished items are taxed when sold to consumers.

SUBSIDIZING PURCHASES TO SPUR PROPERTY DEVELOPMENT To support a return of businesses to parts of lower Manhattan following the 2001 terrorist attack on the World Trade Center, New York State exempts the purchase and use of certain items used to outfit, furnish, and equip commercial office space in that zone.

Taxpayers, employers, and lenders to governments should demand that states develop and sharpen oversight protocols for all large tax expenditures. This means defining why every expenditure program was created, tracking its impact, measuring how it may shift a financial burden from some taxpayers onto others, and regularly testing legislators’ interest in continuing it. Without these steps, tax expenditure programs can distort the operation of a state tax system. States should be improving tax expenditure research, reporting, and transparency so that when legislatures must make decisions about paying for needed infrastructure upgrades, they can optimize tax rate-setting for affordability, efficiency, and equity.

In the following pages, we define what is typically meant by the term “tax expenditure” and discuss why states tend to reallocate taxpayer burdens in this fashion. We look closely at the perils of state inattention to tax expenditure effectiveness and what states can do to better analyze this portion of their budgets. We conclude with recommendations for states to improve the evaluation and disclosure of tax expenditures and offer suggestions for stakeholders, including taxpayers and investors in the $4 trillion municipal securities market, to help them seek better transparency into tax expenditures and their results. In a toolkit section following the conclusions and policy recommendations, we present a set of report cards (Appendix A) in which we assess and describe the wide variety of oversight and disclosure review of tax expenditures in six states: Alabama, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, Utah, and Washington. The report cards are followed by a survey (Appendix B) of tax expenditures and disclosure in all fifty states.

DEFINING TAX EXPENDITURES

The Tax Policy Center, a joint venture of the Urban Institute and Brookings Institution, describes tax expenditures as “forgone revenues from special provisions in the tax code such as exclusions, deductions, deferrals, credits, and preferential tax rates that benefit specific activities or groups of taxpayers.” A tax exclusion (or exemption) is money or value received by a taxpayer that is specifically kept out of definitions of gross income (exclusions reduce a taxpayer’s liability before it is calculated). Deductions also reduce taxable income but are either broadly applied or pertain to specific items that are subtracted rather than being excluded from the outset. Deferrals allow taxpayers to postpone the realization of specific portions of their taxable income or tax liability into future years. Tax credits reduce a taxpayer’s liability after that liability is calculated and so do not change taxable income. Preferential tax rates tax income or assets from one source at a lower than standard rate.4

Consistent with this and other standard definitions, we consider the term “tax expenditure” to mean a specific provision of law that reduces a taxpayer’s bill versus what it would be without that provision. So, a preferential tax rate of 3 percent for a favored group of taxpayers versus the standard 4 percent would be viewed as a tax expenditure.

Public disclosure in budgets and other official documents of tax expenditures and associated policy goals and costs is vital to help ensure scarce public resources to programs are allocated to achieve intended objectives. In the federal context, the Congressional Research Service, under the terms of the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974, regularly prepares reports on the purpose, costs, and outcomes of US government tax expenditures.5 The US Treasury and White House also issue annual reports including the tax preferences’ purposes and costs. States that follow the federal example and produce regular and frequent disclosure of tax expenditures, and establish robust evaluation processes, are in a better position to gauge the full cost of such programs and their impact on the economy and society.

HOW TAX EXPENDITURES ARE REPORTED

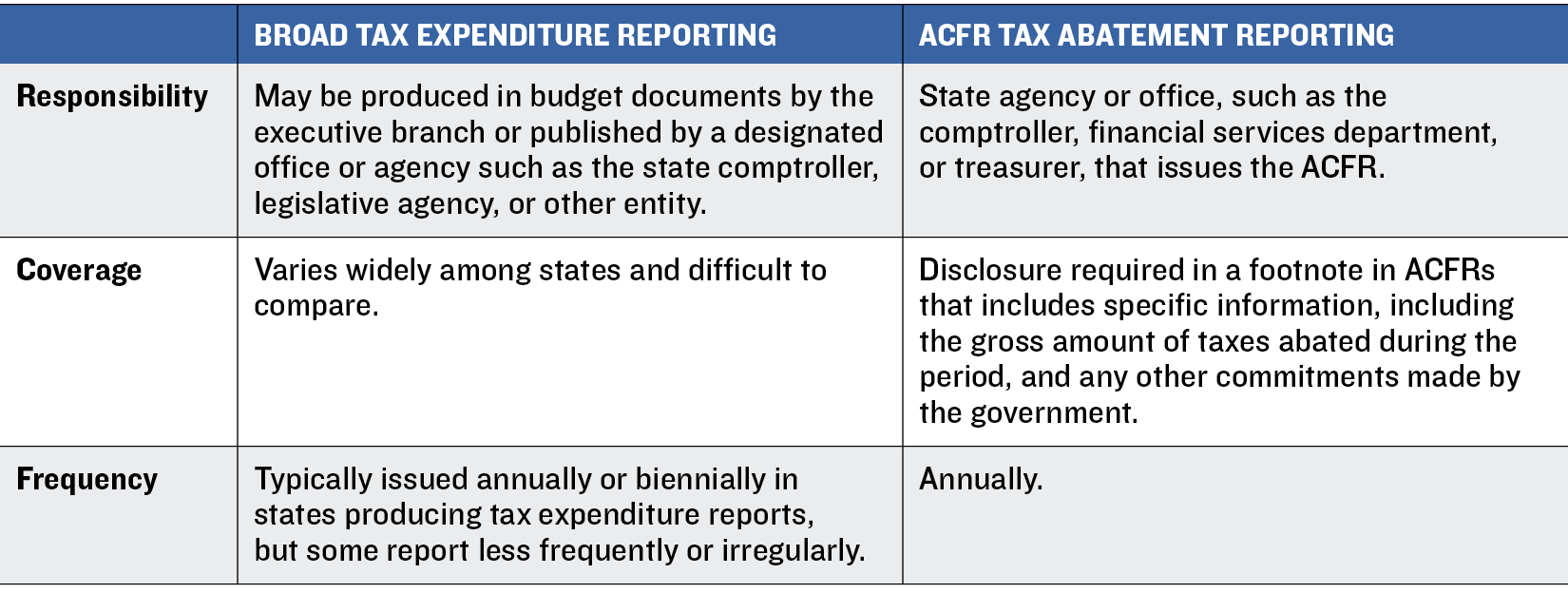

THERE ARE MANY FLAVORS OF TAX EXPENDITURES. Most states disclose at least some costs annually or periodically in budgetary documents or similar reports issued by state comptrollers or legislative offices. The information contained in these documents is not standardized among governments and often differs from disclosures contained in the annual comprehensive financial reports (ACFRs) that states, localities, and other public agencies and institutions issue to investors and the public. These reports focus on a type of business-related tax break called an abatement and are prepared under guidelines promulgated by the Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB), the standard-setter for state and municipal financial reporting. In 2015, GASB began requiring reasonably standardized reporting of tax abatements in ACFRs under its Statement No. 77.

In the statement, GASB defines an abatement as “a reduction in tax revenues that results from an agreement between one or more governments and an individual or entity in which (a) one or more governments promise to forgo tax revenues to which they are otherwise entitled and (b) the individual or entity promises to take a specific action after the agreement has been entered into that contributes to economic development or otherwise benefits the governments or the citizens of those governments.”6 In the following table, we show the differences between typical budget-based tax expenditure reporting and ACFR-based abatement disclosure.

TAX EXPENDITURES VERSUS DIRECT EXPENDITURES

Direct expenditures allocate budgeted revenues for government operations and programs. Tax expenditures distribute forgone revenues to help deliver public services, provide benefits to individuals or corporations, or to guide behavior in a certain way.

The political narrative around tax expenditures contributes to their use. Since the effect of tax expenditures is a reduction in tax revenue, legislators can characterize them as tax cuts, often considered favorably by constituents.

Direct spending and tax expenditures can achieve similar policy goals, but tax expenditures are “off-budget” and therefore often persist unchecked over multiple budget cycles. Because states must balance their budgets, by statute, constitution, or longstanding custom, tax expenditures may conceal potential revenue shortfalls that need to be closed in a given fiscal period.

THE COST OF TAX EXPENDITURES

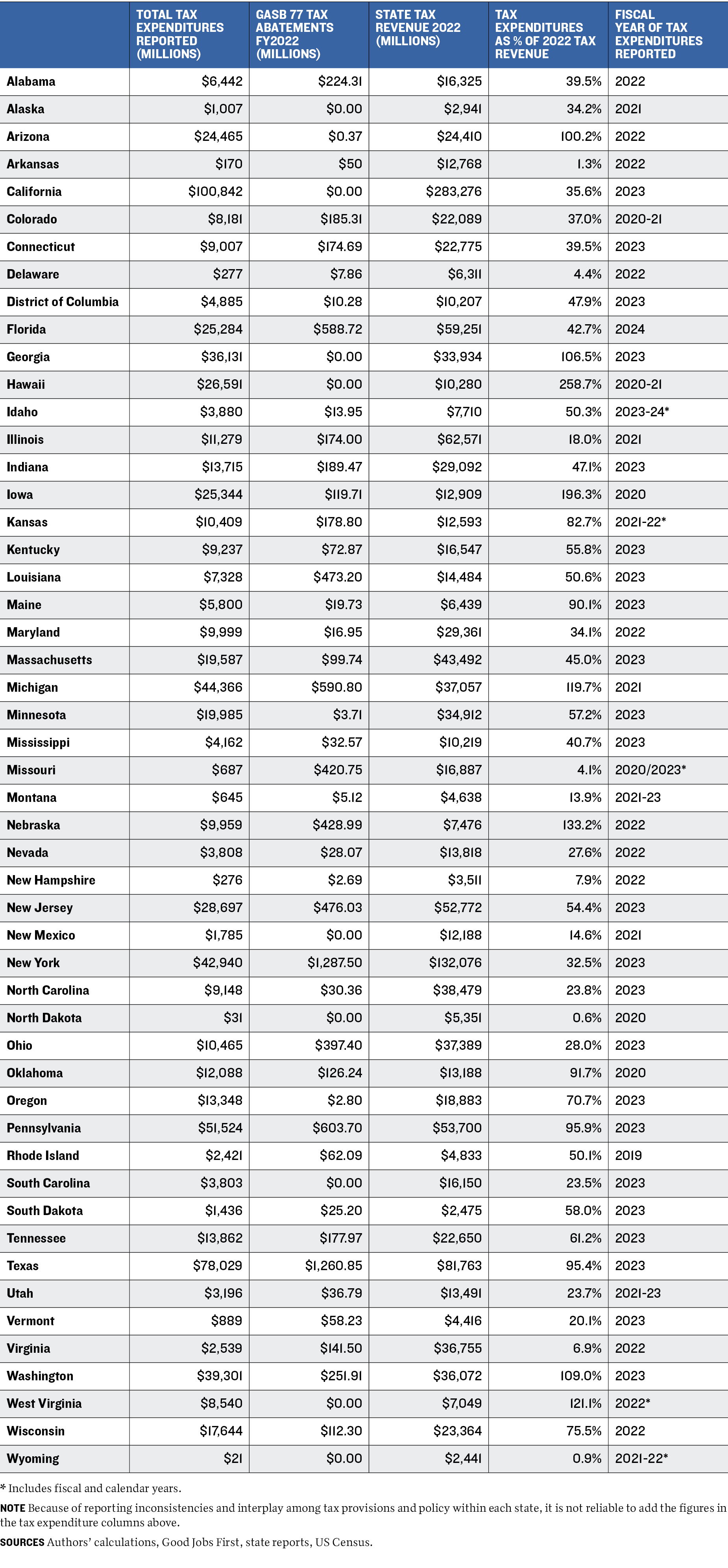

States could generate at least an estimated 50 percent increase in annual tax revenues were it not for tax expenditures. The nearly $1 trillion in such tax expenditures could be used to implement broader or more effectively targeted tax relief, improve infrastructure, ready the country to be more resilient to the effects of climate change, bolster social and equity initiatives, or provide other vital services to the public.

This estimate (Appendix B) is based on the amount of forgone revenues reported by each state in their publicly available tax expenditure reporting. The estimate is most useful as an indication of the magnitude of tax code spending compared to direct spending. Because states’ methodologies and definitions vary widely, estimating the total cost of states’ tax expenditures is an inexact exercise. Additionally, there is no uniformity in the format, timing or frequency of tax expenditure reporting across the states, further undermining the ability to understand the true aggregate cost on a national level.

Some states consider mirroring federal deductions, credits, and other tax preferences as tax expenditures. Just over half of states use the federal figure for adjusted gross income as the starting point for state income tax base; many, but not all, conform to the federal definition of corporate income. Since tax expenditures related to federal tax conformity often amount to a significant amount of forgone revenue,7 this reporting inconsistency substantially obscures direct comparisons across states.

The lack of consistency extends to other categories. New Jersey’s largest individual income tax expenditure, for instance, is the $4.7 billion credit allowed for income paid to other jurisdictions, such as neighboring New York,8 while Delaware excludes such a credit from its report. Some states include a threshold for reporting tax expenditures (California for one, only lists expenditures over $5 million9), and many states have a number of listed tax expenditures for which no estimate is calculated (about half of New Jersey’s 250 listed items lack a dollar estimate).

One type of tax expenditure that should, in theory, be more comparable across states is a tax abatement, which requires standardized disclosure. The total reported amounts of such abatements, however—$9.16 billion in 2022—represent only a small fraction of total state tax expenditures.10

TAX EXPENDITURE RISKS

Many tax expenditures are beneficial to growth and are politically popular. For example, the exclusion of retirement income from state personal income taxes may help long-term residents remain in their communities as they age. Deductions to offset the costs of installing energy-efficient appliances to encourage reduced carbon emissions and improve air quality can benefit current and future state residents. Tax credits or rebates for businesses can increase local employment and expand industry within a state.

Because tax expenditures reduce the tax liabilities of certain taxpayers, they can make it harder for a state to raise revenue. Tax expenditures also reallocate the tax burden among taxpayers, favoring some at the cost of others. At worst, this can create distortions (say, if a tax expenditure creates a competitive advantage for one industry versus another). Overly broad income tax exemptions may also compel a state to rely more on user fees and charges, such as increased public university tuition, which may limit residents’ economic mobility.

Tax expenditures often go unchecked, potentially continuing long after the intended policy outcome was achieved. In many states, most reported tax expenditures were enacted decades ago; about 80 percent of Minnesota’s tax breaks, for example, were put in place before 2000.11 Over years or decades, changes in a state’s economy, industrial base, or the federal tax code may negate intended policy impacts, worsen stakeholder equity issues, or undermine aggregate economic growth. For example, the COVID-19 pandemic brought long-lasting changes to many state economies and tax rolls as more employees opted to work from home and relocate to other states. The pandemic’s impact on current tax expenditure programs thus warrants increased scrutiny.

NEW YORK'S $43 BILLION TAX BREAKS MAY CONFLICT WITH CLIMATE, INFRASTRUCTURE INVESTMENT NEEDS

NEW YORK’S LARGE, COMPLEX, AND LOOSELY MANAGED system of tax expenditures, amounting to $42.94 billion in fiscal 2023,12 is equivalent to 32.5 percent of overall tax revenue for 2022.13 While the tax expenditures support affordable housing production, job creation, and other meritorious goals, they also limit revenues required to meet the state’s considerable and growing infrastructure funding challenges.

Consider the recently suspended congestion pricing fee for motorists entering much of Manhattan. The state-owned Metropolitan Transportation Authority, the intended recipient of the congestion pricing proceeds, may find itself billions of dollars short of funds for urgently needed capital improvements. If the suspension is not lifted, the state will become increasingly reliant on new revenue creation measures to pay for deferred mass transit maintenance and new investment.

Costs like these are likely to rise rapidly as the effects of more severe weather trends become clearer. The state may also find that it will need to start bearing more of the cost of local climate adaptation projects if counties, cities, and towns lack the financial resources to fund them on their own.

In 2023, New York’s Office of the State Comptroller released a survey of local government climate adaptation spending, finding that New York City alone spent about $2 billion in fiscal 2023, while other local governments were only getting started on planning projects and estimating costs.14 The burden of massive new investment programs could stretch the state’s ability to raise sufficient funding without undue economic disruption. An analysis and recalibration of tax expenditure measures might reduce the economic and political risk of having to enact large tax increases to make up for lost revenue.

But oversight of New York’s tax expenditures by the governor and legislature is limited. Under state law, the executive branch produces an annual comprehensive report on tax expenditures for submission to the legislature. The report includes statutory details on how each program operates and any proposed modifications from the governor, but there is no discussion of policy goals or performance indicators.

The state also lacks a formal, systematic review system or statutory sunsetting requirements for tax expenditures, although it has periodically subjected programs to an ad hoc oversight process. The latest of these was undertaken in 2023 via a state-funded study of the impacts and efficiencies of economic development incentives, Economic Impact of Tax Incentive Programs.15 While the study found value in monitoring and limiting state tax incentives, it failed to recommend specific changes in state law.

In contrast to the state’s lack of systemic tax expenditure scrutiny, the state-owned Empire State Development agency, which promotes business investment and job creation through tax credits, grants, loans, and other incentives, provides details on its website on the tax expenditures it offers. Its reporting includes a searchable database, performance indicators, and limited reporting on individual incentive programs.16

Federal legislation enacted during and after the pandemic provided hundreds of billions of dollars of grants and tax credits in such areas as transportation, renewable energy, broadband, and semiconductor manufacturing. Many states have piggybacked on the federal programs with local tax incentives. For example, New York’s Green CHIPS legislation allows certain semiconductor manufacturers to receive tax credits under the state’s Excelsior Jobs Program. By providing additional state incentives on top of federal incentives in the CHIPS and Science Act, New York is increasing its attractiveness as a location for chip makers.17

EVALUATING TAX EXPENDITURES

Regular assessments of the goals, costs, and evidence-based outcomes of tax expenditures are essential tools for ensuring the prudent use of scarce public resources. Efforts by the Pew Charitable Trusts over the past decade, for example, sharpened many states’ focus on the design and evaluation of economic development incentives, often considered the most controversial form of tax breaks. Pew’s research, engagement with states, and capacity-building efforts with the National Conference of State Legislatures resulted in growth in the number of states adopting laws and processes that guide the establishment, cost, and evaluation of new and existing economic development incentive programs.18

Examples of states initiating or changing tax expenditure scrutiny include:

• COLORADO In 2016, Colorado enacted legislation that requires the state auditor to review all types of tax expenditures at least once every five years and that the Legislative Oversight Committee Concerning Tax Policy considers resulting policy considerations. The state tax expenditure evaluation process includes identifying goals of an expenditure; measuring its effectiveness against its stated objective, including an explanation of the performance measure used; assessing its economic costs and benefits and making recommendations on how to remove any barriers in such assessments; evaluating the cost-effectiveness of the incentive relative to other options to achieve the program’s stated goal; and analyzing its impact on competition, business, and stakeholder needs.19

• MINNESOTA In 2018, a House Research Department report, Tax Expenditures vs. Direct Expenditures: A Primer, lays out what legislators may want to evaluate when deciding whether to use tax breaks or direct spending to support a policy goal. The report encourages comparing each option in terms of policy and institutional considerations, such as ease of administration, behavioral effects, impact on the tax system, and interaction with federal tax treatment.20

• NEW JERSEY In 2020, New Jersey enacted improvements to state economic development programs, including caps on incentive awards and third-party reporting on the effectiveness of the largest programs every two years. The state still lacks a systemic review process for evaluating its total menu of tax expenditures, however.21

• UTAH In 2016, the state passed legislation requiring the Office of the Legislative Fiscal Analyst to evaluate economic development state tax credits every three years and for the legislature’s Revenue and Taxation Interim Committee to recommend whether the tax breaks should be continued, modified, or repealed. The evaluation considers the cost of the tax credit to the state, its purpose and effectiveness, and the benefit to the state.22

• WASHINGTON A 2006 law requires all tax expenditures to be reviewed on a ten-year cycle by the staff of the nonpartisan Joint Legislative Audit and Review Committee. The committee then recommends which incentives should continue, be modified, or ended. A separate group, the Citizen Commission for Performance Measurement of Tax Preferences, was charged with creating a schedule for the reviews, holding public hearings, and commenting on the evaluations. Since the law took effect, Washington has continued to improve its ability to oversee and measure each new tax expenditure by requiring that a statement is included for each program that discloses its purpose, how effectiveness will be measured, and which data will be needed for such a review.23

Several other states addressed shortcomings in tax expenditure oversight:

• MAINE In 2018, the legislative Office of Program Evaluation and Review corrected a flaw in the state’s Pine Tree Development Zones program. While businesses with new or increased operations in designated zones had been eligible for program benefits, legislation and administrative rules failed to ensure benefits accrued only to businesses adding qualifying jobs. The fix included a measure requiring businesses to prove they had created at least one eligible job before they could receive incentives.24

• VIRGINIA In 2020, the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission concluded that the state’s coal tax credits were obsolete and should be eliminated.25 The credits cost the state about $300 million in fiscal 2010-18, enough to cover the average annual salary of 450 to 500 state troopers. The credits were initially put in place to maintain the competitiveness of the state coal industry and to encourage the use of Virginia coal for power generation. Legislators elected to phase out the tax break in 2021 after finding that all but one coal-fired power plant was scheduled to be shuttered by 2025 and that the credit was producing negligible benefits.26

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

With $1 trillion in public resources at stake annually through the provision of tax abatements, credits, deductions, and exemptions, states should adopt a comprehensive, statutory code of conduct to ensure the programs authorizing such tax breaks are well-designed, carefully monitored, and routinely evaluated based on evidence.

Such a code of conduct should include:

• Clear delineation of the policy reasons for each major tax expenditure item, covering existing tax expenditures and those proposed for inclusion in future budgets. For new tax expenditures, the reason for choosing to allocate resources through the tax code versus direct spending should be plainly stated.

• Creation of key performance indicators to evaluate every major tax expenditure. This tracking should not only report how many dollars are being redirected from one group of taxpayers to another, but also how effectively the specific expenditure is satisfying its original or adjusted policy intention.

• Establishment of standard provisions for the expiration of every state tax expenditure (and review of federal tax code conformance provisions), including periodic reevaluations and reauthorizations by the legislature and governor.

• Publication of a resource allocation budget that reports direct spending and tax expenditure estimates by budget category. This would allow a fuller and more transparent accounting of where potential resources are being directed.

• Commitment of permanent, professional staff and administrative resources to analyze and track tax expenditures to ensure technical competence and consistent reporting across legislative and budget cycles.

Additionally, stakeholders, such as taxpayers, lenders, and investors in municipal bonds, should urge governments to improve disclosure and evaluation of tax expenditures to ensure that they are employed productively. For example:

• Individual and corporate taxpayers should seek precise reporting on tax expenditures to ensure existing tax burdens are not inequitably or inefficiently allocated.

• Bond buyers and other lenders should consider whether states with large tax expenditure programs are potentially less able to fund essential operating programs or capital improvements with tax increases.

APPENDIX A: SIX STATE REPORT CARDS

WE EXAMINED THE USE AND REPORTING of tax expenditures by six states with widely different policies on transparency and oversight: Alabama, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, Utah, and Washington. Among them, Washington and Minnesota are notably more transparent, as shown by their statutory review processes, while Alabama, New Jersey, New York, and Utah are less open in their reporting and less systematic in their reviews. We find that even the best states can improve their tax expenditure oversight and disclosure. In the following pages, we provide report cards on the six states.

ALABAMA

DESPITE RECENT IMPROVEMENTS in the transparency and oversight of some tax expenditures, Alabama has failed to adopt a reliable analytical approach. The Legislative Services Agency prepares an annual report that lists all tax expenditures and their related costs. The report is reviewed by a joint committee of the legislature, which may suggest potential revisions to the full body. The nature of the review is not specified by state law, and the joint committee’s suggestions are only advisory. No other review is conducted, and state tax expenditures are not automatically subject to expiration or performance measurement, although a 2023 law provides this for economic development incentives created under the Alabama Jobs Act. That law awards companies tax credits for qualified capital investments and cash rebates for payroll costs.27

DESPITE RECENT IMPROVEMENTS in the transparency and oversight of some tax expenditures, Alabama has failed to adopt a reliable analytical approach. The Legislative Services Agency prepares an annual report that lists all tax expenditures and their related costs. The report is reviewed by a joint committee of the legislature, which may suggest potential revisions to the full body. The nature of the review is not specified by state law, and the joint committee’s suggestions are only advisory. No other review is conducted, and state tax expenditures are not automatically subject to expiration or performance measurement, although a 2023 law provides this for economic development incentives created under the Alabama Jobs Act. That law awards companies tax credits for qualified capital investments and cash rebates for payroll costs.27

Alabama Tax Expenditure Questions and Answers

DOES THE STATE PRODUCE A TAX EXPENDITURE REPORT? Yes. The Fiscal Division of the Legislative Services Agency is required by statute to prepare and submit an annual report to the legislature listing all state tax expenditures and the estimated costs associated with each.28

WHAT DOES THE STATE CONSIDER A TAX EXPENDITURE? Tax expenditures are provisions of law that allow for special treatment of a source of income or certain types of expenses that results in a reduction in the tax liability for a taxpayer or group of taxpayers. In Alabama, these expenditures are established by statute and, in some cases, the state constitution. Generally, the tax benefits realized by a taxpayer or group of taxpayers could be provided by direct appropriation; therefore, the provisions are referred to as “expenditures.” Expenditures represent revenues that would have otherwise been generated if not for preferential treatment.29

HOW MANY TAX EXPENDITURES ARE REPORTED? About 500.30

HOW OFTEN IS THE REPORT ISSUED? Annually.

HOW MANY YEARS ARE COVERED BY THE REPORT? Estimates for current budget year, with one-year history for comparison to total revenues.

WHAT IS THE VALUE OF TAX EXPENDITURES RELATIVE TO TAX REVENUES? State tax expenditures were reported to be $6.44 billion in fiscal 2022,31 equivalent to 39.5 percent of $16.32 billion in tax revenue for the year.32

DOES THE STATE SUBJECT ALL TAX EXPENDITURES TO A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW PROCESS? The Joint Legislative Advisory Committee on Economic Incentives, created by a 2015 law,33 monitors the state Department of Commerce’s management and standards for awarding economic development incentives allowed by law. The department, assisted by the Revenue and Finance departments, reports tax expenditure costs to the joint committee annually. The committee is advisory and operates under its own rules; its process for evaluating the information it receives is unclear.

DO OTHER PARTIES REVIEW TAX EXPENDITURES? The Enhancing Transparency Act of 2023 requires the Department of Commerce to assess the impact of all economic development agreements signed pursuant to the Alabama Jobs Act. The scrutiny includes counting the number of jobs created and estimated ten- and twenty-year returns to the state on the value of incentives.34 This information is provided to the Joint Legislative Advisory Committee and, as of 2024, is published on the Commerce Department website.35

ARE SUNSET PROVISIONS REQUIRED FOR TAX EXPENDITURE PROGRAMS? There are no standard sunset provisions.36

MINNESOTA

UNDER 2021 LEGISLATION, Minnesota is on track to implement several improvements to its tax expenditure oversight. The newly established Tax Expenditure Review Commission is responsible for reviewing tax expenditures and evaluating effectiveness and fiscal impact. Under the legislation, each tax expenditure must be evaluated on a rotating basis at least once every ten years. Public hearings must be held on the findings of the evaluation process and a report must be submitted to legislative committees with jurisdiction over tax policy. In addition, under the 2021 law, any new tax expenditure or expiring tax expenditure being renewed must include a sunset provision of no longer than eight years from enactment.37

UNDER 2021 LEGISLATION, Minnesota is on track to implement several improvements to its tax expenditure oversight. The newly established Tax Expenditure Review Commission is responsible for reviewing tax expenditures and evaluating effectiveness and fiscal impact. Under the legislation, each tax expenditure must be evaluated on a rotating basis at least once every ten years. Public hearings must be held on the findings of the evaluation process and a report must be submitted to legislative committees with jurisdiction over tax policy. In addition, under the 2021 law, any new tax expenditure or expiring tax expenditure being renewed must include a sunset provision of no longer than eight years from enactment.37

Minnesota Tax Expenditure Questions and Answers

DOES THE STATE PRODUCE A TAX EXPENDITURE REPORT? Yes, the commissioner of the Department of Revenue submits a tax expenditure budget report to the legislature by November 1 of each even-numbered year.38

WHAT DOES THE STATE CONSIDER A TAX EXPENDITURE? A tax expenditure is a provision that provides a gross income definition, deduction, exemption, credit, or rate for certain persons, types of income, transactions, or property that results in reduced tax revenue. This excludes provisions used to mitigate tax pyramiding, such as sales tax collections on intermediate business-to-business transactions. Items must be preferential to be considered a tax expenditure (a standard deduction would not be one). Items also must include only exceptions to the defined base tax; exclude those that are subject to an alternative tax (such as a motor vehicle sales tax versus the general sales and use tax); and must be subject to legislative authority (not tax provisions contained in federal law or the state or US constitutions).39

HOW MANY TAX EXPENDITURES ARE REPORTED? About 320.40

HOW OFTEN IS THE REPORT ISSUED? Biennially, in even-numbered years.

HOW MANY YEARS ARE COVERED BY THE REPORT? The report includes estimates of annual tax expenditures for at least three years, including the two-year period covered in the governor’s budget submitted the preceding January.

WHAT IS THE VALUE OF TAX EXPENDITURES RELATIVE TO TAX REVENUES? State tax expenditures were reported to be $19.99 billion in fiscal 2023,41 equivalent to 57.2 percent of $34.91 billion in tax revenue for fiscal 2022.42

DOES THE STATE SUBJECT ALL TAX EXPENDITURES TO A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW PROCESS? Yes. Legislation passed in 2021 requires that each of the state’s tax expenditures be evaluated on a regular, rotating basis at least once every ten years. The evaluation must include a recommendation to continue, modify, or repeal each tax expenditure. A public hearing must be held and include a presentation of the findings of the evaluation process, and a report must be submitted to the legislative committees with jurisdiction over tax policy, which must also conduct a public hearing on the matter.43

DO OTHER PARTIES REVIEW TAX EXPENDITURES? Yes. The Tax Expenditure Review Commission, created by 2021 legislation, reviews tax expenditures and evaluates their effectiveness and fiscal impact. The commission includes two senators appointed by the body’s majority leader; two senators appointed by the minority leader; two representatives appointed by the house speaker; two representatives appointed by the house minority leader; and the state commissioner of revenue or the commissioner’s designee.44

ARE SUNSET PROVISIONS REQUIRED FOR TAX EXPENDITURE PROGRAMS? Yes. Legislation passed in 2021 requires that any bill creating a new tax expenditure or continuing an expiring one must include an expiration date that is no more than eight years from the day the provision takes effect.45

NEW JERSEY

NEW JERSEY REGULARLY PRODUCES a tax expenditure report that includes the purpose of each tax preference and its cost. The New Jersey Economic Recovery Act of 2020 included changes that improve some processes and oversight of the state’s economic development programs, including caps on incentive awards, a requirement for third-party reporting on the effectiveness of the largest programs every two years, and the establishment of an Office of Inspector General to detect, monitor, and investigate fraud or abuse in the programs. The state lacks a systematic evaluation process for tax expenditures, however, and most do not include sunset provisions.46

NEW JERSEY REGULARLY PRODUCES a tax expenditure report that includes the purpose of each tax preference and its cost. The New Jersey Economic Recovery Act of 2020 included changes that improve some processes and oversight of the state’s economic development programs, including caps on incentive awards, a requirement for third-party reporting on the effectiveness of the largest programs every two years, and the establishment of an Office of Inspector General to detect, monitor, and investigate fraud or abuse in the programs. The state lacks a systematic evaluation process for tax expenditures, however, and most do not include sunset provisions.46

New Jersey Tax Expenditure Questions and Answers

DOES THE STATE PRODUCE A TAX EXPENDITURE REPORT? Yes. State law requires that the governor’s annual budget message include a tax expenditure report. The Division of Taxation of the Department of the Treasury assists in preparation of the report.47

WHAT DOES THE STATE CONSIDER A TAX EXPENDITURE? The Division of Taxation defines tax expenditures as “only those tax-revenue-reducing provisions explicitly specified under state law. These generally fall into five categories of preferential tax treatment: exemptions, exclusions, deductions, credits and direct property tax relief.”48

HOW MANY TAX EXPENDITURES ARE REPORTED? About 250.49

HOW OFTEN IS THE REPORT ISSUED? Annually.

HOW MANY YEARS ARE COVERED IN THE REPORT? The report covers three years and includes the last completed fiscal year, the current fiscal year and the fiscal year covered by the budget message.50

WHAT IS THE VALUE OF TAX EXPENDITURES RELATIVE TO TAX REVENUES? State tax expenditures were reported to be $28.7 billion in fiscal 2023,51 equivalent to 54.4 percent of $52.77 billion in tax revenue for the year.52

DOES THE STATE SUBJECT ALL TAX EXPENDITURES TO A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW PROCESS? No. Some economic development incentive programs include reporting provisions.

DO OTHER PARTIES REVIEW TAX EXPENDITURES? There is no requirement for any other party to systematically review the tax expenditures, although the legislature is informed in the governor’s annual budget message of their estimated fiscal impact.

ARE SUNSET PROVISIONS REQUIRED FOR TAX EXPENDITURE PROGRAMS? There are no standard sunset provisions.53

NEW YORK

TAX EXPENDITURES LACK comprehensive oversight by the state’s executive branch and legislature. Although the executive branch produces an annual report detailing each program and any proposed modifications, it fails to include policy goals or performance indicators. The state also lacks a formal review system or statutory sunsetting requirements for tax expenditures. Instead, programs are subjected to ad hoc oversight, such as a 2023 independent study that analyzed economic development incentives and recommended monitoring, spending caps, sunsetting provisions, and accountability measures.54

TAX EXPENDITURES LACK comprehensive oversight by the state’s executive branch and legislature. Although the executive branch produces an annual report detailing each program and any proposed modifications, it fails to include policy goals or performance indicators. The state also lacks a formal review system or statutory sunsetting requirements for tax expenditures. Instead, programs are subjected to ad hoc oversight, such as a 2023 independent study that analyzed economic development incentives and recommended monitoring, spending caps, sunsetting provisions, and accountability measures.54

An exception to the general paucity of reporting and evaluation is Empire State Development, the umbrella organization for New York’s two main economic development entities, which promotes business investment and job creation through tax credits, grants, loans, and other incentives. This agency provides some ongoing analytical resources for tax incentives, including a searchable database and performance indicators for individual programs.55

New York Tax Expenditure Questions and Answers

DOES THE STATE PRODUCE A TAX EXPENDITURE REPORT? Yes. The governor is required by statute to submit to the legislature annually a list of tax expenditures, including their basis in law; cost estimates for each; recommendations for continuing, changing, or repealing each provision; and comments on their effectiveness.56 In addition, Empire State Development, maintains a searchable database of tax expenditures provided by the organization, along with performance indicators.57

WHAT DOES THE STATE CONSIDER TAX EXPENDITURES? The state defines tax expenditures as “features of the tax law that by exemption, exclusion, deduction, allowance, credit, preferential tax rate, deferral, or other statutory device, reduce the amount of taxpayers’ liabilities to the state by providing either economic incentives or tax relief to particular classes of persons or entities, to achieve a public purpose.”58

HOW MANY TAX EXPENDITURES ARE REPORTED? About 430.59

HOW OFTEN IS THE REPORT ISSUED? Annually.

HOW MANY YEARS ARE COVERED IN THE REPORT? Generally, five years of historical data and one year of projections, where data are available.

WHAT IS THE VALUE OF TAX EXPENDITURES RELATIVE TO TAX REVENUES? State tax expenditures were reported to be $42.94 billion in fiscal 2023,60 equivalent to 32.5 percent of $132.08 billion in tax revenue for 2022.61

DOES THE STATE SUBJECT ALL TAX EXPENDITURES TO A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW PROCESS? There is no known formal review process for expenditures beyond the annual report on tax expenditures from the executive branch’s Division of the Budget. The legislature and agencies may engage in ad hoc reviews of specific programs.62 Empire State Development, in contrast, provides statistics on jobs created and costs to taxpayers for the tax expenditure programs that it operates.63

DO OTHERS REVIEW TAX EXPENDITURES? The Department of Taxation and Finance provides some reporting, as does the state comptroller.64

ARE SUNSET PROVISIONS REQUIRED FOR TAX EXPENDITURE PROGRAMS? There are no standard sunset provisions.65

UTAH

UTAH IMPROVED THE REVIEW of state economic development tax credits through 2016 legislation. The legislature’s Revenue and Taxation Interim Committee is required to review these tax credits every three years and recommend if they should be continued, modified, or repealed. The evaluation considers the cost of the tax credit to the state, its purpose and effectiveness, and any benefits to the state. Reporting and reviewing of other tax expenditures is less robust. The Utah State Tax Commission’s annual report includes the estimated cost for the year of many tax expenditures affecting sales tax revenues. Systematic review of these and many other tax expenditures is lacking.66

UTAH IMPROVED THE REVIEW of state economic development tax credits through 2016 legislation. The legislature’s Revenue and Taxation Interim Committee is required to review these tax credits every three years and recommend if they should be continued, modified, or repealed. The evaluation considers the cost of the tax credit to the state, its purpose and effectiveness, and any benefits to the state. Reporting and reviewing of other tax expenditures is less robust. The Utah State Tax Commission’s annual report includes the estimated cost for the year of many tax expenditures affecting sales tax revenues. Systematic review of these and many other tax expenditures is lacking.66

Utah Tax Expenditure Questions and Answers

DOES THE STATE PRODUCE A TAX EXPENDITURE REPORT? There is not a comprehensive one. Some tax exemptions and credits are reported by the Utah State Tax Commission. For example, sales tax exemptions are detailed in the commission’s annual report. The total amount claimed under corporate tax credits, individual income tax credits, election campaign checkoff contributions and individual income tax credits are also reported separately.67

WHAT DOES THE STATE CONSIDER A TAX EXPENDITURE? A 2016 legislative report defines an economic exception or inducement as an exemption, deduction, credit, preferential rate, or other tax benefit that reduces a taxpayer’s state or local tax liability or results in a refund. Economic incentives may also include a program where revenue is dedicated to pay for aspects of development, including community revitalization, enterprise zones, or a tax increment financing district.68 Under state law, the Office of the Legislative Fiscal Analyst must evaluate corporate and income tax credits, with additional analysis by the governor’s Office of Economic Development, which administers many incentives.69 Reporting of amounts claimed under corporate and individual income tax credits and election campaign checkoff contributions is done by the tax commission. Sales tax exemptions are reported separately in the commission’s annual report.70

HOW MANY TAX EXPENDITURES ARE REPORTED? There is no single report, but the state offers more than 170 tax exemptions.71

HOW OFTEN IS THE REPORT ISSUED? Some reporting is provided annually.

HOW MANY YEARS ARE COVERED IN THE REPORT? Not applicable.

WHAT IS THE VALUE OF TAX EXPENDITURES RELATIVE TO TAX REVENUES? State tax expenditures were approximately $3.2 billion in fiscal 2022,72 equivalent to 23.7 percent of $13.49 billion in tax revenue for the year.73

DOES THE STATE SUBJECT ALL TAX EXPENDITURES TO A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW PROCESS? No, although state law mandates reviews of certain tax credits.74,75

DO OTHER PARTIES REVIEW TAX EXPENDITURES? The Revenue and Taxation Interim Committee reviews certain credits.76,77

ARE SUNSET PROVISIONS REQUIRED FOR TAX EXPENDITURE PROGRAMS? There are no standard sunset provisions.

WASHINGTON

AMONG THE SIX STATES STUDIED, Washington appears to have the most longstanding and advanced policies promoting tax expenditure reporting and oversight. With few exceptions, each tax expenditure is reviewed every ten years by the staff of the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Committee. The reviews are based on schedules set by the Citizen Commission for Performance Measurement of Tax Preferences, whose voting members include appointees of the House, Senate, and governor. The panel’s reviews are guided by a set of questions tailored to the tax expenditure studied. The result is a detailed and publicly available analysis that includes the public policy purpose of the tax preference; its beneficiaries, the revenue impact (and the impact if terminated); and its success measured against predefined metrics. The commission evaluates the analysis, conducts public hearings, and provides to a joint hearing of the legislative fiscal committees a commentary and recommendation on continuing the tax expenditure.78

AMONG THE SIX STATES STUDIED, Washington appears to have the most longstanding and advanced policies promoting tax expenditure reporting and oversight. With few exceptions, each tax expenditure is reviewed every ten years by the staff of the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Committee. The reviews are based on schedules set by the Citizen Commission for Performance Measurement of Tax Preferences, whose voting members include appointees of the House, Senate, and governor. The panel’s reviews are guided by a set of questions tailored to the tax expenditure studied. The result is a detailed and publicly available analysis that includes the public policy purpose of the tax preference; its beneficiaries, the revenue impact (and the impact if terminated); and its success measured against predefined metrics. The commission evaluates the analysis, conducts public hearings, and provides to a joint hearing of the legislative fiscal committees a commentary and recommendation on continuing the tax expenditure.78

Washington Tax Expenditure Questions and Answers

DOES THE STATE PRODUCE A TAX EXPENDITURE REPORT? Yes. State law requires the Department of Revenue to submit to the legislature a study that lists exemptions for major state and local taxes in Washington, starting in 1984 and due in January of every fourth year thereafter.79

WHAT DOES THE STATE CONSIDER A TAX EXPENDITURE? The report must contain a list of the amount of reduction for the current and next biennium in the revenues of the state or local government collected by the state as a result of tax exemptions. The listing must include an estimate of revenue lost from a tax exemption; its purpose; the persons, organizations, or parts of the population benefitting from the exemption; and whether or not the measure conflicts with another state program. The report must include real and personal property tax exemptions; business and occupational exemptions, deductions, and credits; sales and use exemptions; public utility exemptions and deductions; fish and shellfish exemptions; leasehold excise tax exemptions; motor vehicle and special fuel tax exemptions and refunds; and insurance premiums tax exemptions.80

HOW MANY TAX EXPENDITURES ARE REPORTED? About 750.81

HOW OFTEN IS THE REPORT ISSUED? Every four years.

HOW MANY YEARS ARE COVERED IN THE REPORT? Estimates for current year and subsequent biennium.82

WHAT IS THE VALUE OF TAX EXPENDITURES RELATIVE TO TAX REVENUES? State tax expenditures were projected to be $39.3 billion in fiscal 2023,83 more than the $36.07 billion in tax revenue collected in 2022.84

DOES THE STATE SUBJECT ALL TAX EXPENDITURES TO A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW PROCESS? The tax exemption study should include a description of each exemption, its intended purpose, estimates of taxpayer savings, effect on state and local revenue, and the possible impact of repeal. Legislators have also required that every new tax preference measure include an expiration date and statement of legislative intent.85,86

DO OTHERS REVIEW TAX EXPENDITURES? The revenue department must provide listings of reduction in revenues from tax exemptions to the legislature, with the assistance of other agencies or departments as required. The report must also be presented to the House and Senate Ways and Means committees in public hearings. The governor reviews the report and may submit recommendations to the legislature to repeal or modify any tax exemption.87

ARE SUNSET PROVISIONS REQUIRED FOR TAX EXPENDITURE PROGRAMS? Yes, starting with measures enacted since 2014.88

APPENDIX B: STATE TAX EXPENDITURES AND REPORTING

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

THIS REPORT WAS MADE POSSIBLE in part by a grant from the Peter G. Peterson Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author. We acknowledge the considerable support provided by the late Paul A. Volcker, the Volcker Alliance’s founding chairman, as well as the numerous academics, government officials, and public finance professionals who have guided the Alliance’s research on state budgets for the last seven years. Mr. Volcker was especially interested in the subject of tax breaks provided by states and encouraged the Alliance’s public finance team to include consideration of the reporting of tax expenditures in the Truth and Integrity in State Budgeting reports. We are also grateful for the longtime support and guidance of the late Richard Ravitch, the former New York State lieutenant governor and founding Alliance board member, who died in June 2023.

Special thanks to Nicholas Sourbis, managing director at Municipal Market Analytics Inc., for research on state tax expenditure programs. This study builds on the work of others who have described and analyzed state tax expenditures, intending to amplify and perhaps sharpen some of their findings as the cost of related opacity has increased and become more immediate for all stakeholders. Among these publications are the Center on Budget Policy and Priorities’ 2011 report, Promoting State Budget Accountability Through Tax Expenditure Reporting, the Progressive Policy Institute’s 2014 report, The State Tax Complexity Index: A New Tool for Tax Reform and Simplification, the Tax Policy Center’s 2020 brief, State Income Tax Expenditures, and the 2022 report by the Pew Charitable Trusts, Best Practices for States Planning Tax Incentive Evaluations. The Tax Foundation has also weighed in on state policy in the 2023 report: Does Your State Have a Sales Tax Holiday? We also look to the work done by states themselves, many producing reporting and analysis on all or parts of their tax expenditure systems. Especially useful was the 2022 comprehensive guide, State-by-State Tax Expenditure Reports, compiled by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy.

ENDNOTES

1. US Census Bureau, “2021 Annual Surveys of State and Local Government Finances,” Table 1, State and Local Government Finances by Level of Government and by State: 2021, https://www.census.gov/data/datasets/2021/econ/local/public-use-dataset….

2. The amount of forgone revenues attributed to states’ tax expenditures is based on the amounts reported in their tax expenditure disclosure documents and has been adjusted by the authors to reflect omissions and inconsistencies across states. In our calculation of foregone revenues, we assume that all tax expenditures are repealed simultaneously. We do not consider potential responses by individuals and companies, and any resulting impact on state revenues, to such a hypothetical repeal of tax expenditures.

3. US Census Bureau, “2021 Annual Surveys of State and Local Government Finances,” Table 1, State and Local Government Finances by Level of Government and by State.

4. Frank Sammartino and Eric Toder, Tax Expenditure Basics, Tax Policy Center, January 22, 2020, https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/publications/tax-expenditure-basics/full.

5. Congressional Research Service, Tax Expenditures Compendium of Background Material on Individual Provisions, December 15, 2020. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CPRT-116SPRT42597/pdf/CPRT-116SPRT4….

6. Governmental Accounting Standards Board, Statement No. 77 of the Governmental Accounting Standards Board: Tax Abatement Disclosures, August 2015, 2, https://gasb.org/page/ShowPdf?path=gasbs77_final-+Cropped.pdf.

7. The Pew Charitable Trusts, Tax Code Connections: How Changes to Federal Policy Affect State Revenue, February 2016, https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2016/02/fiscalfed_federaltaxpo….

8. State of New Jersey, The State of New Jersey Tax Expenditure Report: Building the Next New Jersey: Affordability, Responsibility and Opportunity, Fiscal Year 2024, https://www.nj.gov/treasury/taxation/pdf/taxexpenditurereport2023.pdf.

9. State of California, Department of Finance, 2022-23 Tax Expenditure Report, https://dof.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/352/Forecasting/Revenue_and….

10. Good Jobs First, “State Tax Revenues Lost to Tax Abatement Programs, 2021,” https://taxbreaktracker.goodjobsfirst.org/?detail=state_list&fiscal_yea….

11. Minnesota Department of Revenue, “2022 Tax Expenditure Summary List,” https://www.revenue.state.mn.us/sites/default/files/2022-10/2022_summar…

12. New York State Division of the Budget, Department of Taxation and Finance, FY 2023 Annual Report on New York State Tax Expenditures, https://www.tax.ny.gov/pdf/research/stats/expenditure-reports/fy23ter.p…

13. US Census Bureau, “2022 State Government Tax Tables,” 2022 Annual Survey of State Government Tax Collections by Category, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2022/econ/stc/2021-annual.html.

14. Office of the New York State Comptroller, New York’s Local Governments Adapting to Climate Change: Challenges, Solutions, and Costs, April 2023, https://www.osc.ny.gov/files/local-government/publications/pdf/climate-….

15. New York State Department of Taxation and Finance, Economic Impact of Tax Incentive Programs, December 30, 2023, https://www.tax.ny.gov/pdf/research/economic-impact-of-tax-incentive-pr….

16. Empire State Development, Tax Credits and Incentives Give New York State Businesses a Competitive Edge, https://esd.ny.gov/tax-basedincentives.

17. Empire State Development, New York State’s Green CHIPS Program: Attracting Semiconductor Partnerships to Create Jobs, Opportunity, and Foster Environmental Sustainability, https://esd.ny.gov/green-chips.

18. Josh Goodman, and Jeff Chapman, “State Tax Incentive Evaluation Ratings,” The Pew Charitable Trusts, May 3, 2017, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2017/05/03/….

19. Colorado S.B. 16-203, Concerning the Evaluation of State Tax Expenditures, and, in Connection therewith, Making an Appropriation, 2016, https://leg.colorado.gov/sites/default/files/2016a_203_signed.pdf.

20. Joel Michael, Tax Expenditures vs. Direct Expenditures: A Primer, House Research Department, December 2018, https://www.house.mn.gov/hrd/pubs/taxvexp.pdf.

21. New Jersey Bill A4 Aca (1R), New Jersey Economic Recovery Act of 2020, 2020, https://www.njleg.state.nj.us/bill-search/2020/A4.

22. Utah H.B. 3001, Tax Credit Review Amendments, 2016, https://le.utah.gov/~2016S3/bills/static/HB3001.html.

23. Revised Code of Washington, Section 43.136, Termination of Tax Preferences, 2023, https://app.leg.wa.gov/RCW/default.aspx?cite=43.136.

24. Josh Goodman and John Hamman, “States Improved Tax Incentive Evaluations in 2018,” March 18, 2019, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2019/03/18/….

25. Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, Infrastructure and Regional Incentives: Economic Development Incentives Evaluation Series, September 14, 2020, https://jlarc.virginia.gov/pdfs/reports/Rpt536-1.pdf.

26. Virginia H.B. 1899, Coal Tax Credits; Sunset Date, 2021, https://lis.virginia.gov/cgi-bin/legp604.exe?212+sum+HB1899&212+sum+HB1….

27. Alabama Department of Commerce, Taxes and Incentives, https://www.madeinalabama.com/business-development/recruitment-andreten….

28. Alabama Code, Section 29-5A-46, Tax Expenditure Report, 2017, https://alison.legislature.state.al.us/code-of-alabama.

29. State of Alabama Legislative Services Agency, Fiscal Division, Tax Expenditures, 2024, 2, https://alison.legislature.state.al.us/files/pdf/lsa/Fiscal/TaxExpendit….

30. State of Alabama Legislative Services Agency, Fiscal Division, Tax Expenditures, 2024, 5.

31. State of Alabama Legislative Services Agency, Fiscal Division, Tax Expenditures, 2023, 6, https://alison.legislature.state.al.us/files/pdf/lsa/Fiscal/TaxExpendit….

32. US Census Bureau, “2022 State Government Tax Tables,” 2022 Annual Survey of State Government Tax Collections by Category.

33. Alabama Code, Section 40-18-379, Income Taxes, 2015, https://alison.legislature.state.al.us/code-of-alabama

34. Alabama Code, Section 40-18-379.1, Fiscal Responsibility and Economic Development, 2023, https://alison.legislature.state.al.us/files/pdf/SearchableInstruments/…

35. Alabama Department of Commerce, “Incentives Records,” https://www.madeinalabama.com/public-records/incentives-records/.

36. State of Alabama Legislative Services Agency, Fiscal Division, Report on Alabama Tax Expenditures, January 2022, 120, https://alison.legislature.state.al.us/files/pdf/lsa/Fiscal/TaxExpendit….

37. Minnesota Statutes Section 3.8855, 2023, Tax Expenditure Review Commission, https://www.revisor.mn.gov/statutes/cite/3.8855.

38. Minnesota Statutes Section 270C.11, 2022, Tax Expenditure Budget, https://www.revisor.mn.gov/statutes/2022/cite/270C.11.

39. Minnesota Department of Revenue, Tax Research Division, State of Minnesota Tax Expenditure Budget: Fiscal Years 2022-2025, https://www.revenue.state.mn.us/sites/default/files/2022-02/2022%20Tax%….

40. Minnesota Department of Revenue, Tax Research Division, State of Minnesota Tax Expenditure Budget: Fiscal Years 2022-2025, 5-25, https://www.revenue.state.mn.us/sites/default/files/2022-02/2022%20Tax%….

41. Minnesota Department of Revenue, Tax Research Division, State of Minnesota Tax Expenditure Budget: Fiscal Years 2022-2025.

42. US Census Bureau, “2022 State Government Tax Tables,” 2022 Annual Survey of State Government Tax Collections by Category.

43. Minnesota Statutes Section 3.8855, 2023, Tax Expenditure Review Commission, https://www.revisor.mn.gov/statutes/cite/3.8855.

44. Minnesota Statutes Section 3.8855, 2023, Tax Expenditure Review Commission.

45. Minnesota Statutes Section 3.192, Requirements for New or Renewed Tax Expenditures, 2023, https://www.revisor.mn.gov/statutes/cite/3.192.

46. New Jersey Bill A4 Aca (1R), New Jersey Economic Recovery Act of 2020.

47. New Jersey Revised Statutes Section 52:27B-20a, State Tax Expenditure Report Included in Governor’s Budget Message, 2023, https://lis.njleg.state.nj.us/nxt/gateway.dll/statutes/1/46239/48573?f=….

48. State of New Jersey, The State of New Jersey Tax Expenditure Report, Fiscal Year 2025: Making New Jersey the Best Place to Raise a Family, 6, https://nj.gov/njbonds/treasury/taxation/pdf/taxexpenditurereport2024.p…

49. State of New Jersey, The State of New Jersey Tax Expenditure Report, Fiscal Year 2025: Making New Jersey the Best Place to Raise a Family.

50. State of New Jersey, The State of New Jersey Tax Expenditure Report, Fiscal Year 2025: Making New Jersey the Best Place to Raise a Family.

51. State of New Jersey, The State of New Jersey Tax Expenditure Report, Fiscal Year 2025: Making New Jersey the Best Place to Raise a Family.

52. US Census Bureau, “2022 State Government Tax Tables,” 2022 Annual Survey of State Government Tax Collections by Category.

53. Nikita Biryukov, “New Jersey’s business tax surcharge lapses as funding needs loom,” New Jersey Monitor, January 3, 2024, https://newjerseymonitor.com/2024/01/03/new-jerseys-business-tax-surcha….

54. New York State Department of Taxation and Finance, Economic Impact of Tax Incentive Programs.

55. Empire State Development, Tax Credits and Incentives Give New York State Businesses a Competitive Edge.

56. New York State Executive Laws Section 181, Tax expenditure reporting, https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/laws/EXC/181.

57. Empire State Development, “Database of Economic Incentives,” March 19, 2024, https://data.ny.gov/Economic-Development/Databaseof-Economic-Incentives….

58. New York State Executive Laws Section 181, Tax expenditure reporting.

59. New York State Department of Taxation and Finance, FY 2023 Annual Report on New York State Tax Expenditures.

60. New York State Department of Taxation and Finance, FY 2023 Annual Report on New York State Tax Expenditures.

61. US Census Bureau, “2022 State Government Tax Tables,” 2022 Annual Survey of State Government Tax Collections by Category.

62. New York State Department of Taxation and Finance, Economic Impact of Tax Incentive Programs.

63. Empire State Development, “Database of Economic Incentives.”

64. Office of the New York State Comptroller, “DiNapoli: Weak Oversight Leads to Tax Breaks for Ineligible Properties,” April 20, 2022, https://content.govdelivery.com/accounts/NYOSC/bulletins/3144727.

65. New York State Department of Taxation and Finance, FY 2023 Annual Report on New York State Tax Expenditures, 119-125.

66. Utah H.B. 3001, Tax Credit Review Amendments.

67. Utah State Tax Commission, Annual Report 2022-2023, https://tax.utah.gov/commission/reports/fy23report.pdf.

68. Utah State Legislature, Office of the Legislative Fiscal Analyst, Evaluating Tax Exceptions and Inducements, October 18, 2016, 1, https://le.utah.gov/interim/2016/pdf/00004489.pdf.

69. Utah Code, Section 59-7-159, Review of credits allowed under this chapter, 2022, http://le.utah.gov/xcode/Title59/Chapter7/59-7-S159.html?v=C59-7-S159_2….

70. Utah State Tax Commission, Annual Report 2022-2023.

71. Utah State Legislature, Office of the Legislative Fiscal Analyst, Evaluating Tax Exceptions and Inducements.

72. Utah State Tax Commission, “Income Credits and Checkoffs,” https://tax.utah.gov/econstats/income/credits-checkoffs.

73. US Census Bureau, “2022 State Government Tax Tables,” 2022 Annual Survey of State Government Tax Collections by Category.

74. Utah Code Section 26B-3-130, Medicaid intergovernmental transfer report—Approval requirements, 2023, https://le.utah.gov/xcode/Title26B/Chapter3/26B-3-S130.html?v=C26B-3-S1….

75. Utah Code Section 41-1a-1206, Registration fees—Fees by gross laden weight, 2024, https://le.utah.gov/xcode/Title41/Chapter1a/41-1a-S1206.html.

76. Utah Code Section 26B-3-130, Medicaid intergovernmental transfer report—Approval requirements.

77. Utah Code Section 41-1a-1206, Registration fees—Fees by gross laden weight.

78. Revised Code of Washington, Chapter 43.136, Termination of Tax Preferences, 2023, https://app.leg.wa.gov/RCW/default.aspx?cite=43.136.

79. Revised Code of Washington, Chapter 43.136, Termination of Tax Preferences.

80. Washington State Department of Revenue, 2020 Tax Exemption Study: A Study of Tax Exemptions, Exclusions or Deductions From the Base of a Tax; a Credit Against a Tax; a Deferral of a Tax; or a Preferential Tax Rate, https://dor.wa.gov/sites/default/files/2022-02/2020_Tax_Exemption_Study….

81. Washington State Department of Revenue, 2020 Tax Exemption Study: A Study of Tax Exemptions, Exclusions or Deductions from the Base of a Tax; a Credit Against a Tax; a Deferral of a Tax; or a Preferential Tax Rate.

82. Revised Code of Washington Section 43.06.400, Listing of reduction in revenues from tax exemptions to be submitted to legislature by department of revenue—Periodic review and submission of recommendations to legislature by governor, 2023, https://app.leg.wa.gov/rcw/default.aspx?cite=43.06.400.

83. Washington State Department of Revenue, 2020 Tax Exemption Study: A Study of Tax Exemptions, Exclusions or Deductions from the Base of a Tax; a Credit Against a Tax; a Deferral of a Tax; or a Preferential Tax Rate.

84. US Census Bureau, “2022 State Government Tax Tables,” 2022 Annual Survey of State Government Tax Collections by Category.

85. Revised Code of Washington Section 82.32.808, Tax preferences—Performance statement requirement, 2023, https://app.leg.wa.gov/RCW/default.aspx?cite=82.32.808.

86. Revised Code of Washington Section 82.32.805, Tax preferences—Expiration dates, 2023, https://app.leg.wa.gov/RCW/default.aspx?cite=82.32.805.

87. Washington State Department of Revenue, 2020 Tax Exemption Study: A Study of Tax Exemptions, Exclusions or Deductions from the Base of a Tax; a Credit Against a Tax; a Deferral of a Tax; or a Preferential Tax Rate.

88. Revised Code of Washington Section 82.32.805, Tax preferences—Expiration dates.

© 2024 VOLCKER ALLIANCE INC.

Published June, 2024

The Volcker Alliance Inc. hereby grants a worldwide, royalty-free, non-sublicensable, non-exclusive license to download and distribute the Volcker Alliance paper titled Benefit or Burden: Evaluating $1 Trillion in State Tax Expenditures (the “Paper”) for non-commercial purposes only, provided that the Paper’s copyright notice and this legend are included on all copies.

This paper was published by the Volcker Alliance as part of its Truth and Integrity in Government Finance Initiative. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Volcker Alliance. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Don Besom, art director; Michele Arboit, copy editor.