Facing State Fiscal Cliffs After COVID-19 Aid Expires

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

In the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (ARPA), Congress provided $350 billion in Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (SLFRF) to shore up budgets and address the economic and human consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic; states and the District of Columbia received $195.3 billion of the total amount. This paper examines states’ initial plans for that money, applying standards for sustainability and transparency set out in the Volcker Alliance’s 2021 report Truth and Integrity in State Budgeting: Preparing for the Storm, as well as in previous Truth and Integrity studies.

Among the most common uses for the recovery funds are investments in water, sewer, broadband, and infrastructure, and repayment of federal loans to state unemployment trust funds. Such one-time uses align with the Alliance’s recommended budget practice to avoid relying on one-time revenues to finance recurring costs. In contrast, states that may be using SLFRF dollars for recurring expenditures, including California, Illinois, and Pennsylvania, are at risk of encountering a so-called fiscal cliff once the cash runs out. In particular, the allocation of lump-sum payments for revenue replacement may imperil budgets when federal funding is exhausted. Additionally, reporting on use of these funds is inconsistent. In many states, the lack of transparency about programs financed by SLFRF will make it more difficult to assess downstream budgetary consequences and hold government officials and agencies appropriately accountable.

This paper presents an overview of the use of SLFRF money by all fifty states and examines the initial plans of the eleven most populous states. We conclude with recommendations to reduce the risk of future budget shortfalls when federal aid expires, and we recommend steps that the states and US Department of the Treasury should take to improve transparency.

INTRODUCTION

State governments play a critical role in the battle against COVID-19. They are providing leadership on public health issues, supplying funding and services to meet essential needs, and managing an unprecedented influx of federal money. This paper addresses one of the largest federal assistance initiatives during the pandemic, the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (SLFRF) program, which was authorized by the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (ARPA). It provides $350 billion to state, local, territorial, and tribal governments to help them respond to COVID-19 and address the pandemic’s toll on individuals, communities, businesses, and government services.

In the paper, we examine state governments’ initial plans for SLFRF spending and how those plans relate to the budget practices evaluated in the Volcker Alliance report Truth and Integrity in State Budgeting: Preparing for the Storm, covering fiscal 2015–19, as well as previous annual studies covering individual years beginning in 2015. We pay specific attention to fiscal sustainability and transparency.1

Fiscal sustainability is especially important in the context of SLFRF, because the program provides appropriations that must be obligated (a term indicating a binding agreement for outlays) by December 31, 2024, and spent by December 31, 2026.2 States that may be using these funds to finance recurring costs, including California, Illinois, and Pennsylvania, could encounter so-called fiscal cliffs when the federal money is no longer available. State governments faced such a situation after the recession of 2007–09, when American Rescue and Reinvestment Act funds ran out just as budget shortfalls were reaching a peak toward the end of 2010.3 To help narrow the gaps, states shed almost 150,000 jobs4 and took actions that included Illinois borrowing $7.2 billion to cover government worker pension contributions5 and California and Florida reducing support for and raising tuitions at public universities.6

This paper relies primarily on information collected from the initial performance reports on recovery plans states had to submit to the US Department of the Treasury by August 31, 2021. State recovery initiatives have continued to evolve since then, so the information presented in this paper should be considered a snapshot of early plans. In most states, allocation of SLFRF requires legislative approval, which may occur as part of the regular budget or of special processes. In some states, the governor has the authority to make decisions about allocations.7 Additional information on use of the program will become available as states assign more funds and submit updated recovery plans to the Treasury by July 31 of each year through 2026. A final report is due March 31, 2027.

We begin with background information on the SLFRF program, followed by a high-level review of the contents of the initial state recovery plans. The focus then shifts to a closer examination of the recovery plans and fiscal 2022 budget documents for the eleven most populous states. (New Jersey, the eleventh-largest state by population as of 2020, was included because it was among the top ten states in the amount of funds received.) We conclude with recommendations on how states can pursue fiscal sustainability and transparency in their use and reporting of the funds.

FEDERAL AID TO STATES UNDER SLFRF

ARPA was the sixth major piece of federal legislation that Congress passed in 2020 and 2021 to address the short- and longer-term impacts of COVID-19. These acts provided direct payments, tax breaks, and loans to state and local governments, corporations, nonprofit organizations, and individuals totaling about $5.4 trillion.8 The total amount of federal COVID-19 aid disbursed or committed as of February 2022 was about $10 trillion, equivalent to about 43 percent of US gross domestic product in 2021. The aid included funds disbursed or committed through legislative actions ($5.0 trillion), administrative actions ($0.8 trillion), and Federal Reserve actions ($4.1 trillion).9

ARPA provided $1.9 trillion of the $10 trillion. As part of the act, Congress provided $195.3 billion for state governments and the District of Columbia through the SLFRF program.10 SLFRF allocations were based on each state’s number of unemployed workers as a percentage of the national total, plus $500 million for each state.11 States in which the unemployment rate exceeded the prepandemic rate by 2 or more percentage points received SLFRF in one payment in 2021, while other states received half in 2021 and will receive the other half in 2022. Thirty states received a single payment; twenty states and the District of Columbia received a split payment.12

Treasury interim and final rules created seven broad categories for the use of SLFRF:

-

Public health

-

Negative economic impacts

-

Services to disproportionately impacted communities

-

Premium pay

-

Water, sewer, and broadband infrastructure

-

Revenue replacement

-

Administrative and other13

Although water, sewer, and broadband are the only areas designated for infrastructure investment, governments can finance other types of capital projects under different expenditure categories. For example, revenue replacement funds can be used to finance infrastructure maintenance or pay-as-you-go projects, such as roads.14 The Treasury’s final rule, issued in January 2022, clarified that SLFRF money can also be used to finance eligible COVID-19-related capital projects, such as certain affordable housing, childcare facilities, schools, or hospitals.15

States can determine category allocations, with the exception of revenue replacement. The final rule lets governments take a standard, $10 million allowance for revenue loss or use a specified formula to calculate the difference between estimated revenue (absent the pandemic) and actual revenue. States make a one-time choice to use the calendar or fiscal year to calculate the revenue reduction at the end of each of the years 2020 through 2023.

Though states have broad latitude in using revenue replacement funds to provide services, they cannot use the funds to pay debt service, cover unfunded accrued pension liabilities, offset revenue losses from tax cuts, or replenish rainy day or other fiscal reserve funds. Notably, SLFRF can be used to make contributions to a state unemployment trust fund to restore the prepandemic balance or to repay federal advances made in specified months during the crisis.16

As of December 2021, twenty states had filed six lawsuits challenging the legality of the ARPA provision that prohibits the use of SLFRF to offset revenue losses that result from changes in state tax law. Some states claimed that the provision is ambiguous, noting wording that includes a reference to “directly or indirectly” offsetting a reduction in tax revenue. They also cited issues such as Congress exceeding its power under the Constitution’s Spending Clause, state sovereignty under the Tenth Amendment, and coercion.17

Also open to question is whether indirect effects of SLFRF dollars might lead to states spending their own revenues on uses barred by the federal law. For example, the injection of revenue replacement funds into a general fund may free up cash for prohibited purposes.

The unprecedented federal aid enacted in 2020–21 to keep people working and the economy afloat has contributed to an increase in personal and corporate income and sales tax revenues. The impact of federal funds, combined with other factors, such as the ability of higher-income earners to work remotely, resulted in greater-than-expected revenue growth in fiscal 2021. This contributed to record-high rainy day fund balances and increases in ending balances of general funds. According to The Fiscal Survey of States, published by the National Association of State Budget Officers, states are expected to spend some of those unexpected budget surpluses in fiscal 2022.18 This could result in their using a portion of these funds for purposes that are not allowed under the SLFRF program.

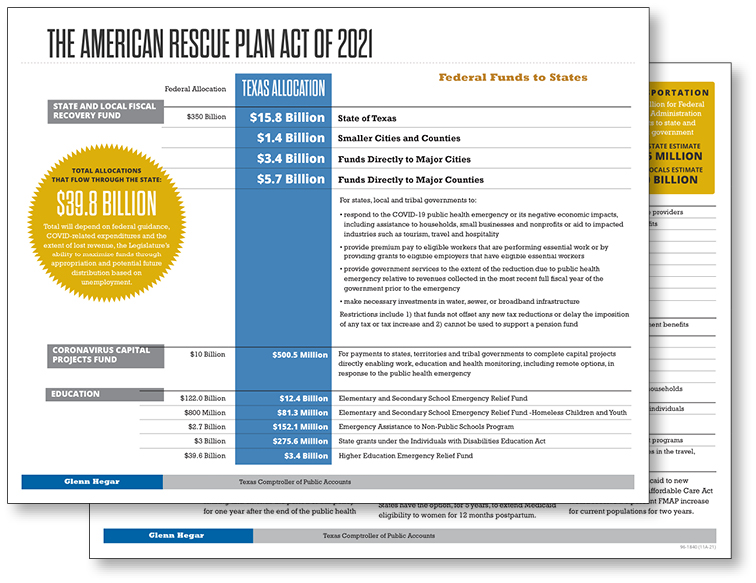

State governments’ decisions on using SLFRF are likely to be informed by what other types of federal assistance they are receiving. Much of the other assistance is restricted to particular purposes. This applies to allocations under the Coronavirus Relief Fund, a part of the 2020 Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, which had to be spent by December 31, 2021. It also includes funding for other ARPA programs, such as $122.7 billion for state and local education agencies in the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund, $39.6 billion for the Higher Education Emergency Relief Fund, $10 billion for the Coronavirus Capital Projects Fund, $21.5 billion for the Emergency Rental Assistance Program, and $10 billion for the Homeowner Assistance Fund.19 The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, passed in November 2021, may also influence SLFRF decisions.

OVERVIEW OF STATES’ INITIAL PLANS FOR USING SLFRF

This section provides a summary of states’ early plans for using SLFRF money. The analysis is based on information obtained from the initial recovery plans submitted by all state governments to the Treasury, covering the period from the program’s initiation through July 2021.20

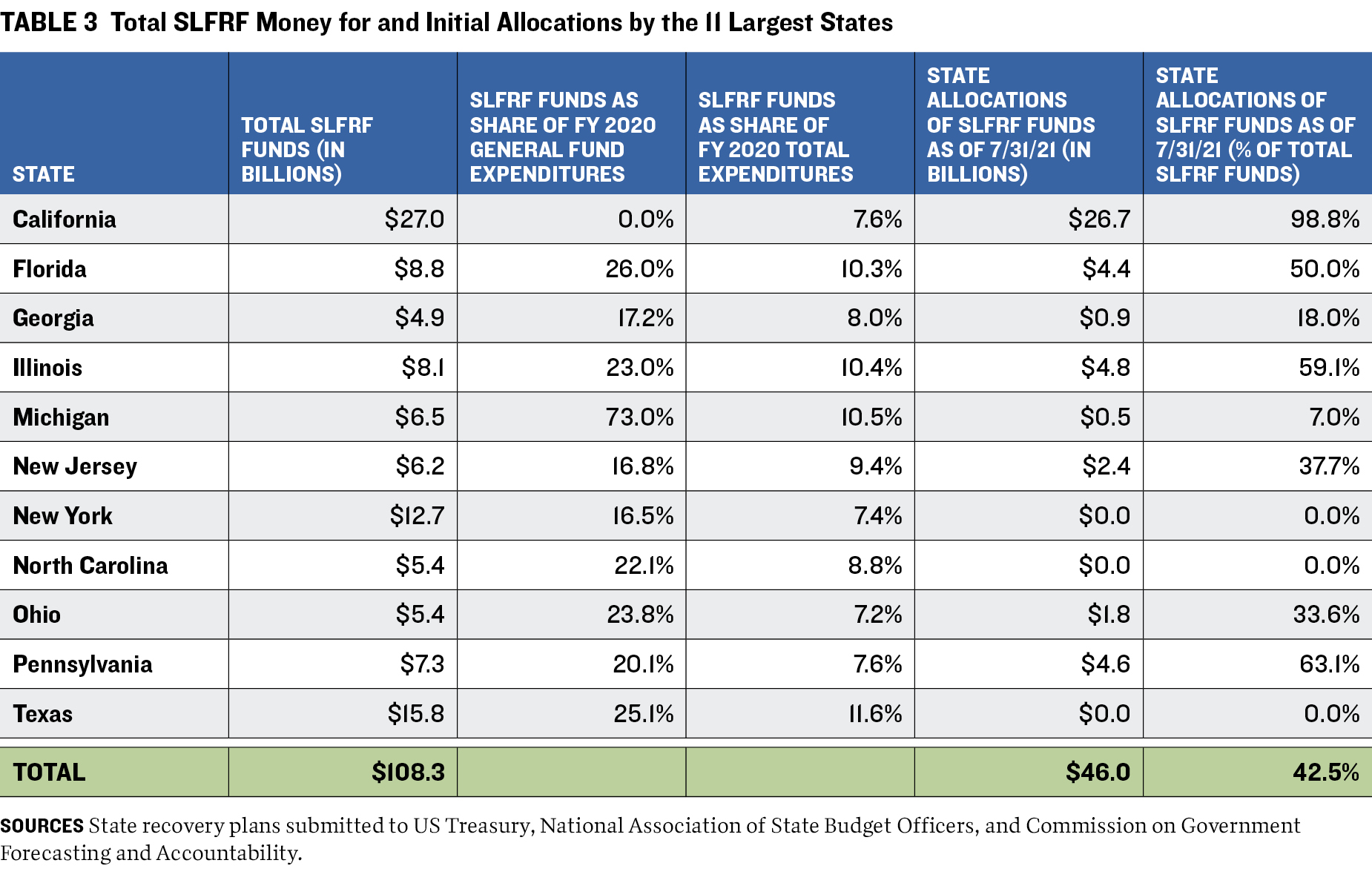

States vary in total SLFRF allocated as of July 31, 2021. In aggregate, they had allocated 43 percent of their total funds. The eleven largest states had allocated less than the thirty-nine others (41 percent versus 46 percent). Fifteen states had not allocated SLFRF to any of the expenditure categories (other than administrative costs), while eight had allocated 80 percent or more. The median allocation was 34 percent.

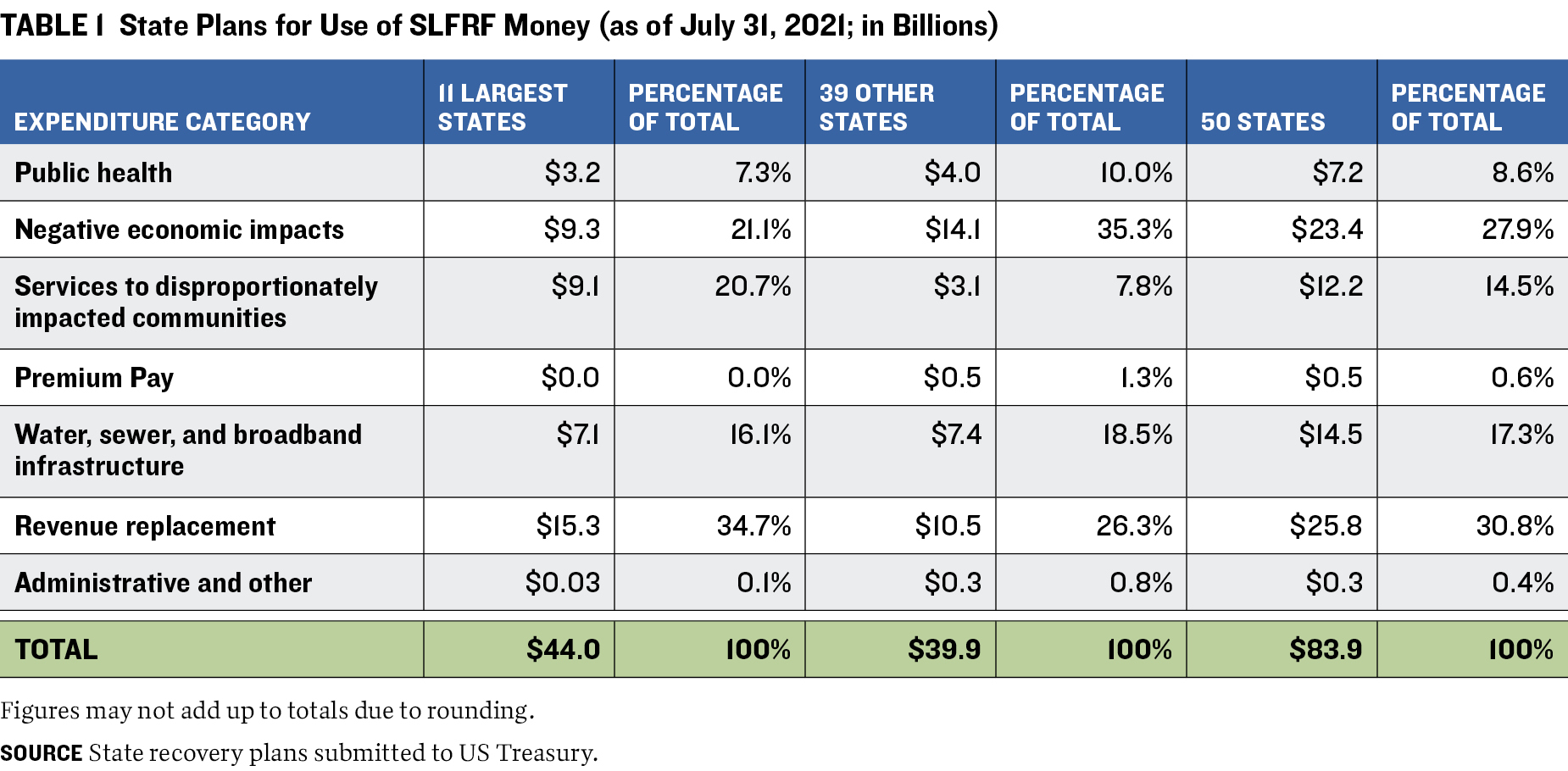

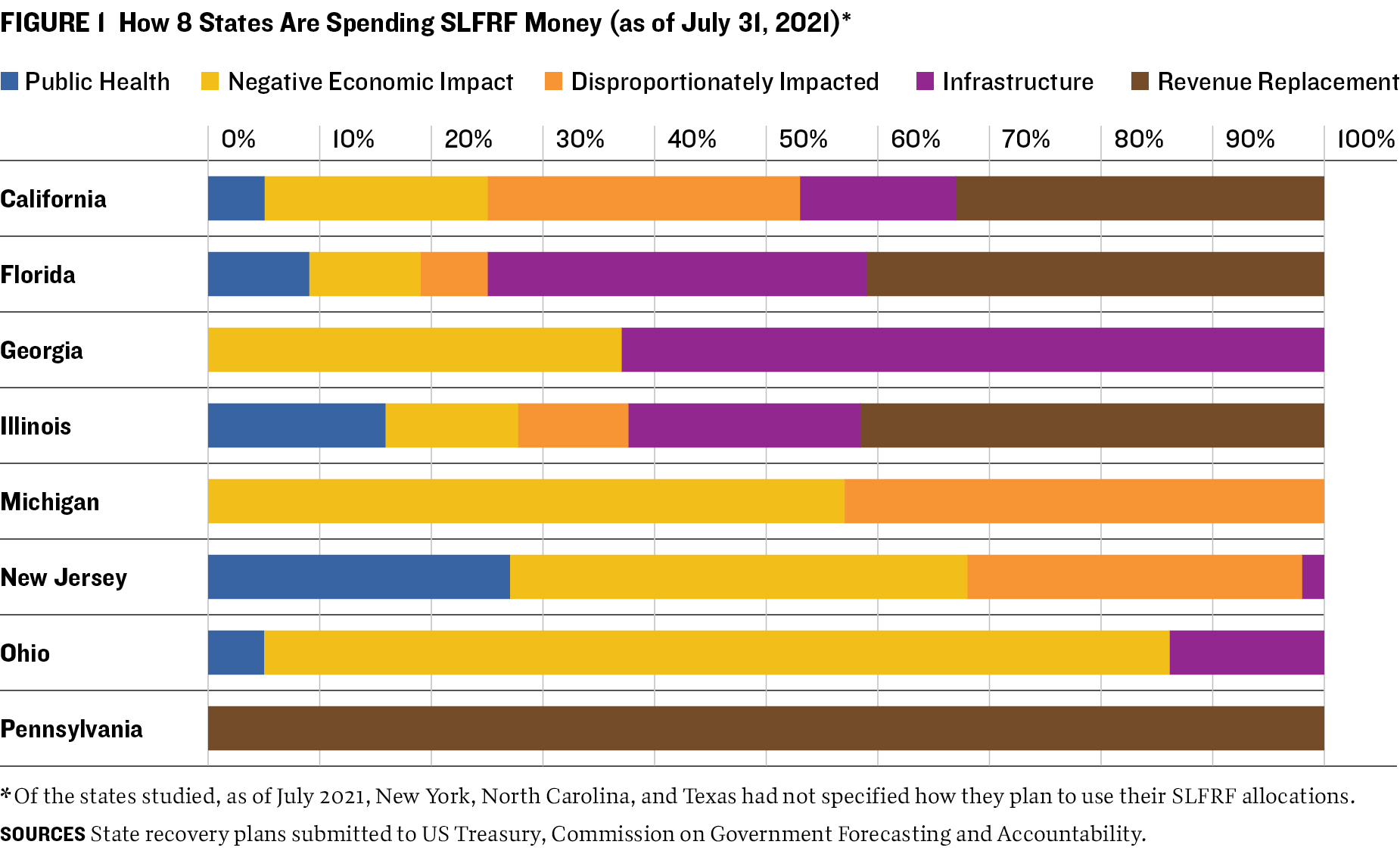

Table 1 shows states’ initial plans for tapping SLFRF.21 For all states, the expenditure categories with the largest allocations were revenue replacement (31 percent); negative economic impacts (28 percent); water, sewer, and broadband infrastructure (17 percent); and services to disproportionately impacted communities (15 percent). The main differences between the allocations by the eleven largest states and the remainder were that the largest assigned more funds to revenue replacement (35 percent versus 26 percent) and services for disproportionally impacted communities (21 percent versus 8 percent). The others allocated a larger percentage to negative economic impacts (35 percent versus 21 percent).

The Alliance’s Truth and Integrity in State Budgeting reports in 2021 and in previous years have found that some states relied on one-time revenues and other impromptu actions to finance recurring costs and attain budgetary balance in the years before the pandemic.22 This paper examines how and whether the grades for large states in two of the five areas of evaluation in the studies—budget maneuvers and transparency—correspond to the initial allocation of SLFRF dollars and reporting about their intended use.

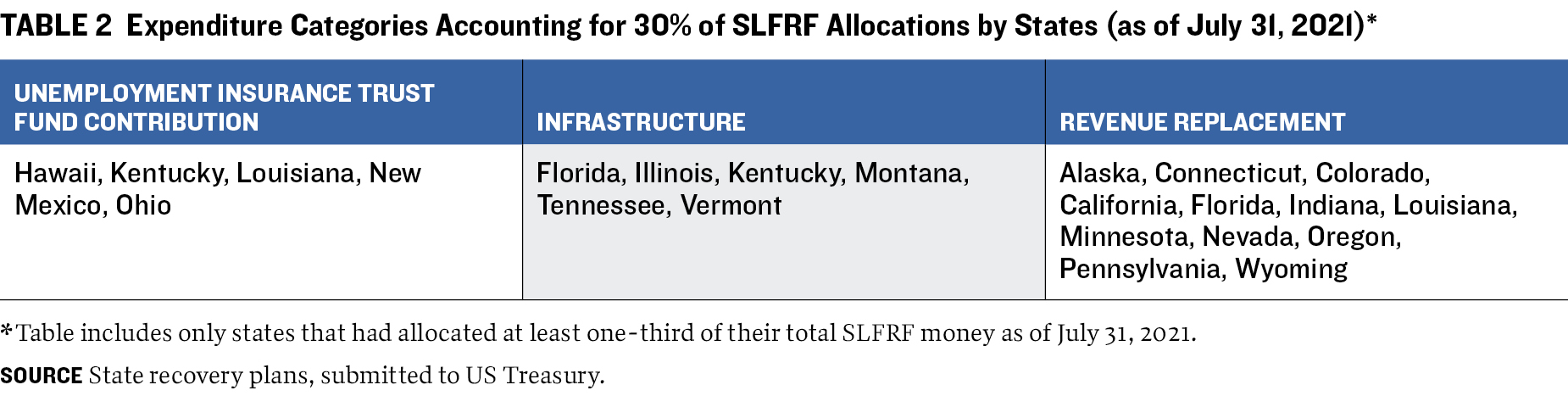

States that use SLFRF for one-time projects are less likely to incur a fiscal cliff than states that devote the dollars to maintaining or expanding services or to creating recurring programs. Because of the one-time nature of the projects, water, wastewater, and broadband infrastructure is one of the more fiscally sound expenditure categories. Seventeen states are using a portion of their SLFRF to fund water or wastewater projects, and eighteen earmarked the funds for broadband. Of the twenty-seven states that had allocated at least one-third of their SLFRF as of July 31, 2021, six devoted 30 percent or more of that money to infrastructure (table 2). States also used money in SLFRF categories other than infrastructure to pay for different types of capital projects, including highways, affordable housing, and construction or renovation of facilities such as hospitals, museums, emergency operation centers, and higher education facilities or schools.

Although such capital projects themselves are one-time spending, states must then pay to operate and maintain the infrastructure or facility. Financing those future needs will require drawing on existing or new revenue sources.

States are also using SLFRF as one-time funds to repay federal loans to their unemployment trust funds. COVID-19 and its related negative economic impacts have put significant stress on unemployment insurance trust funds, which the states and territories operate in partnership with the US government. As jobless numbers rose during the pandemic, many state governments drew down their trust fund reserves, and some borrowed from the federal unemployment trust fund via a mechanism known as a Title XII Advance.

If a state does not repay an advance after a specified period (twenty-two to thirty-four months after the date of the loan, depending on when it was taken), businesses there are subject to a higher federal unemployment tax rate. The rate rises each year until the advance is repaid in full.23 Congress temporarily suspended interest payments on such loans during the first part of the pandemic, but they were reinstated as of September 6, 2021.24

Fourteen states indicated that they plan to use a portion of the SLFRF money to rebuild their unemployment trust funds, either by repaying federal loans or replenishing the trust fund reserves. Of the states that had allocated at least one-third of their SLFRF as of July 31, 2021, five had assigned 30 percent or more of the funds for this purpose (table 2). Some states previously used funds available through the CARES Act this way.25 Using one-time SLFRF to repay federal unemployment trust loans is a budget practice that aligns with Volcker Alliance recommendations. Opponents of using SLFRF to refill unemployment trust funds argue that their balances will increase as the economy improves and joblessness falls.26 On the other hand, those advocating loan repayment say that it will prevent the imposition of a federal tax increase on businesses during the pandemic, allow states to avoid interest costs, and limit the use of SLFRF for recurring spending.27 Replenishing reserve funds can also help prepare for future needs.

States also can use SLFRF for premium pay, another one-time use. In the initial state recovery plans, thirteen states indicated that they planned to provide such supplemental compensation to workers who performed essential services during the COVID-19 emergency. These included frontline employees such as first responders, corrections staff, state police, National Guard, and personnel at health care facilities. States had allocated a total of about $500 million for this category as of July 2021; the individual state amount was generally 5 percent or less of its total allocated funds.

In contrast, the expenditure category that may have the greatest potential to lead to a fiscal cliff is revenue replacement, especially if the funds are used for ongoing purposes. Nineteen states reported that they planned to allocate funds to revenue replacement. Of twenty-seven states allocating at least one-third of their SLFRF as of July 31, 2021, twelve had assigned 30 percent or more to the category (table 2). The percentages ranged from 30 percent in Colorado and 33 percent in California to 100 percent in Pennsylvania and Wyoming.

Whether using SLFRF for revenue replacement will contribute to a budget shortfall when the money is no longer available will depend on how the funds are used. States vary in their plans. For example, Indiana intends to use its $1.45 billion in revenue replacement funds for one-time projects, including road and bridge infrastructure, transit capital spending, conservation and trails, and public safety equipment and training.28 Some states did not identify specific uses for revenue replacement allocations. For example, Connecticut allocated $1.75 billion to support balancing the state budget over two years,29 while Minnesota set aside $1.18 billion to provide government services through fiscal 2025.30

Spreading revenue replacement spending over multiple years could also reduce the magnitude of a fiscal cliff should it be reached.31 For example, a state receiving $1.5 billion in SLFRF and allocating it evenly over three years to cover recurring spending from the general fund would have a budget shortfall of $500 million in the fourth year, if that spending remained the same and no additional revenues were available. Alternatively, if the state allocated all its relief money to the general fund in year one, the shortfall would be $1.5 billion in the second year.

ANALYSIS OF THE eleven largest states’ Initial planS

A closer look at the initial plans for SLFRF by the eleven largest states provides more information about the extent to which states may be allocating funds to one-time versus recurring programs. These states account for 57 percent of US population and 55 percent of total dollars from the program.

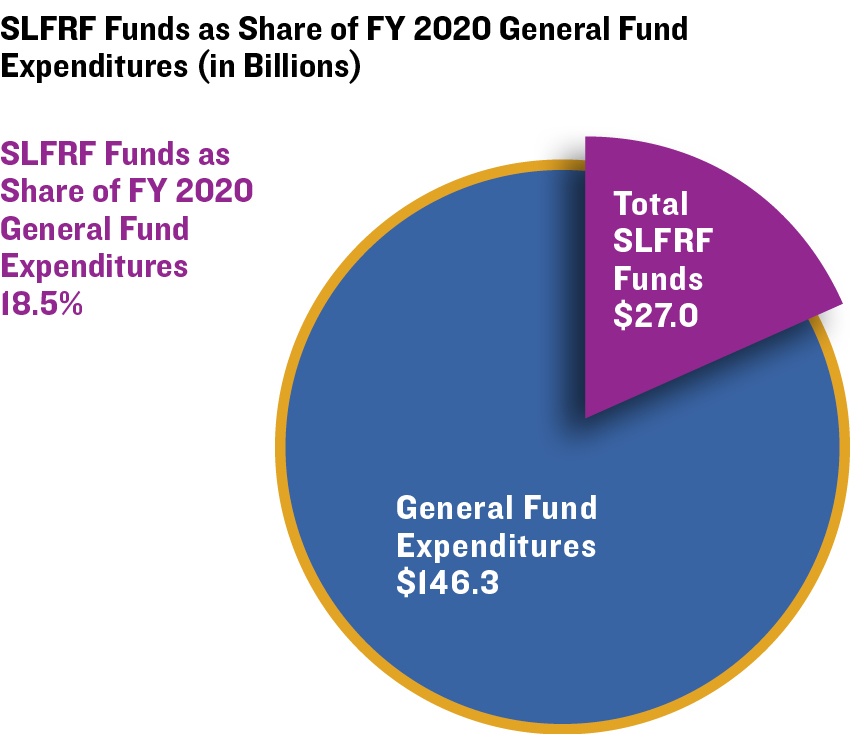

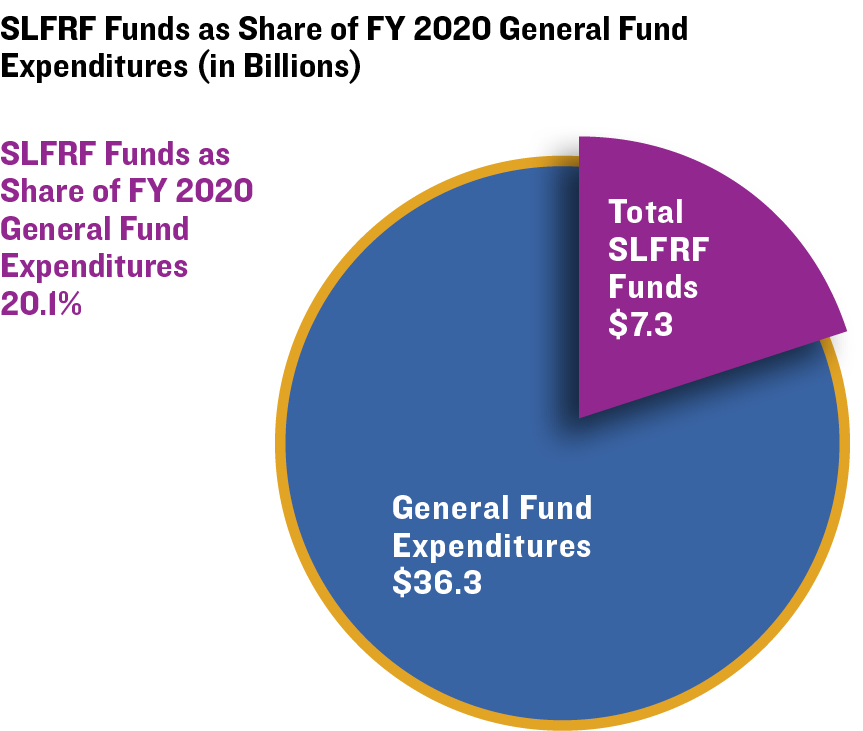

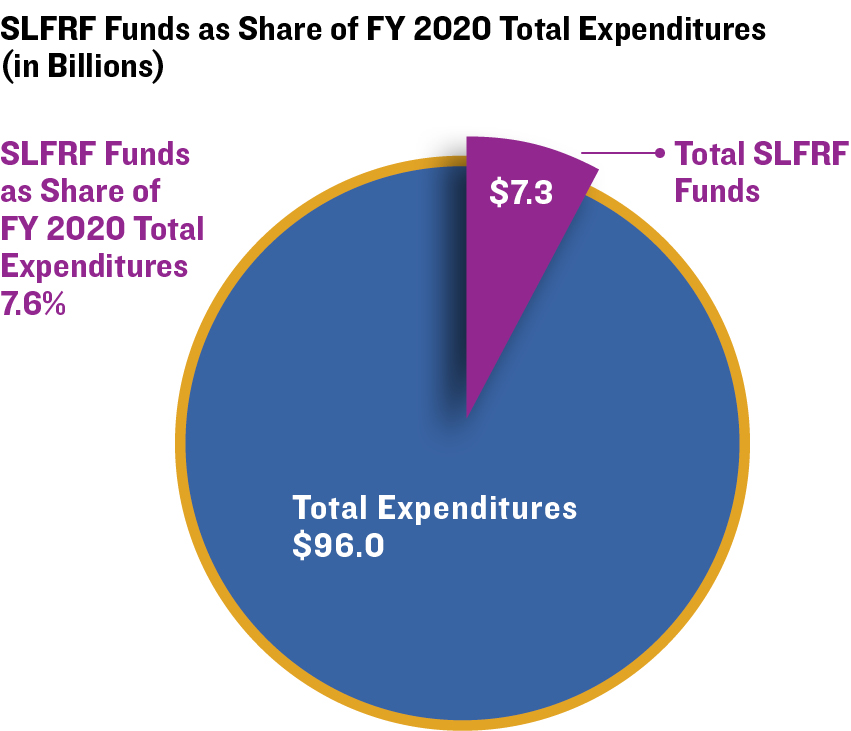

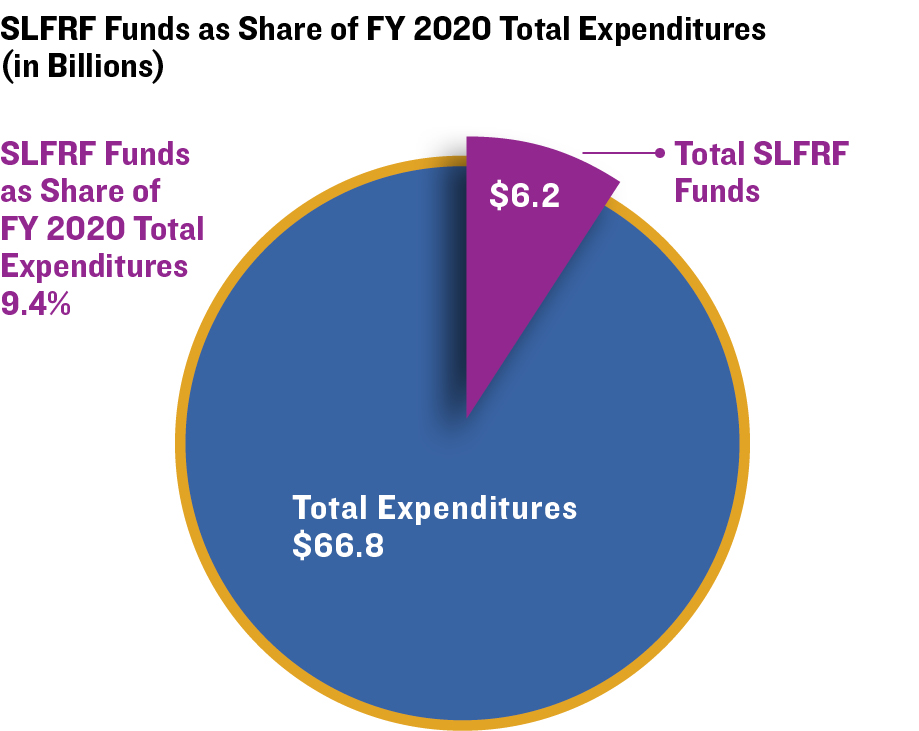

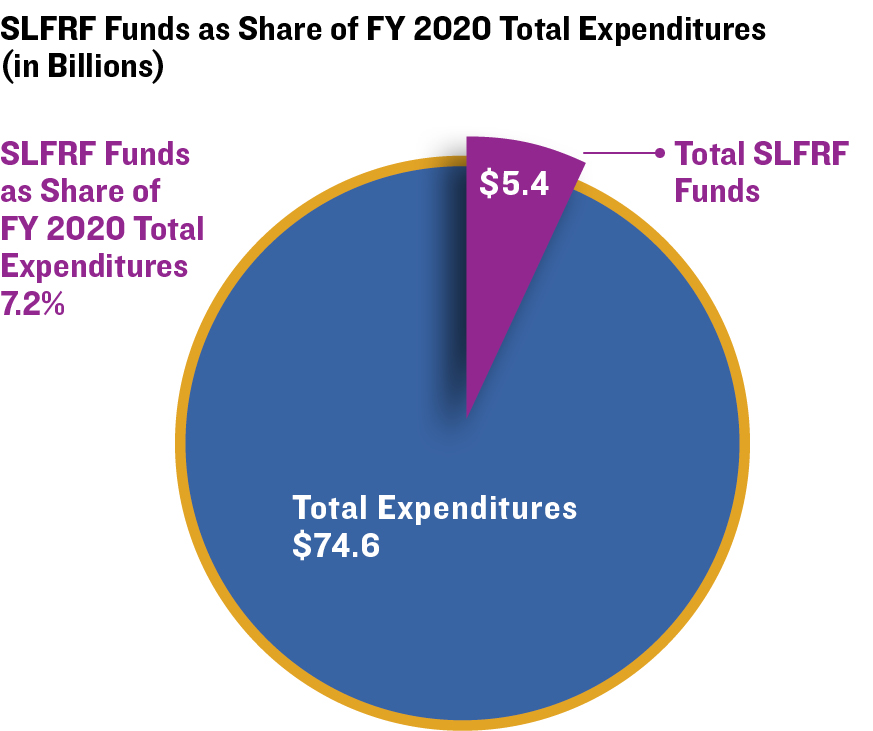

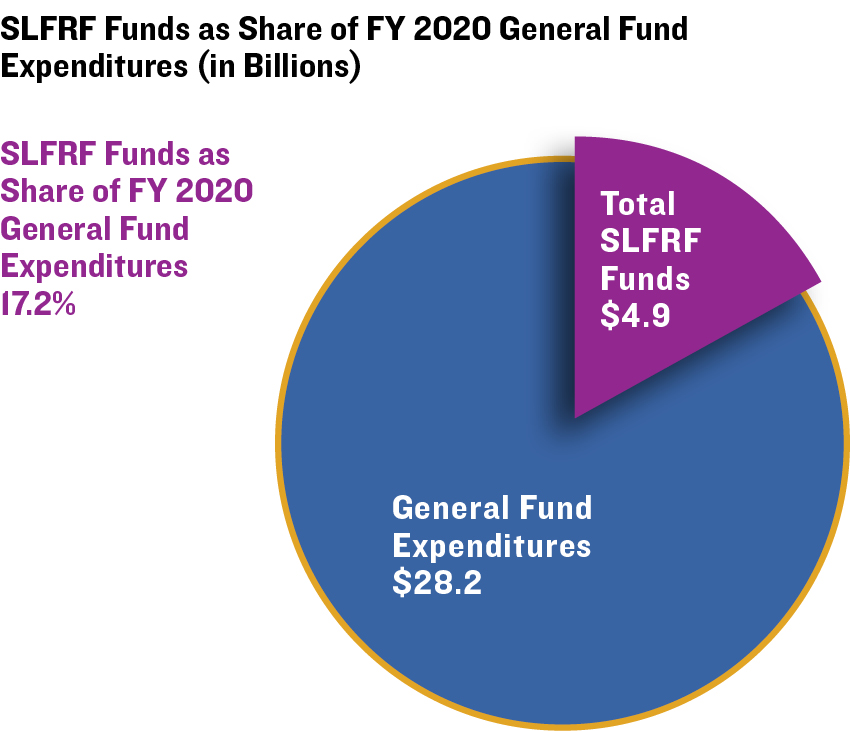

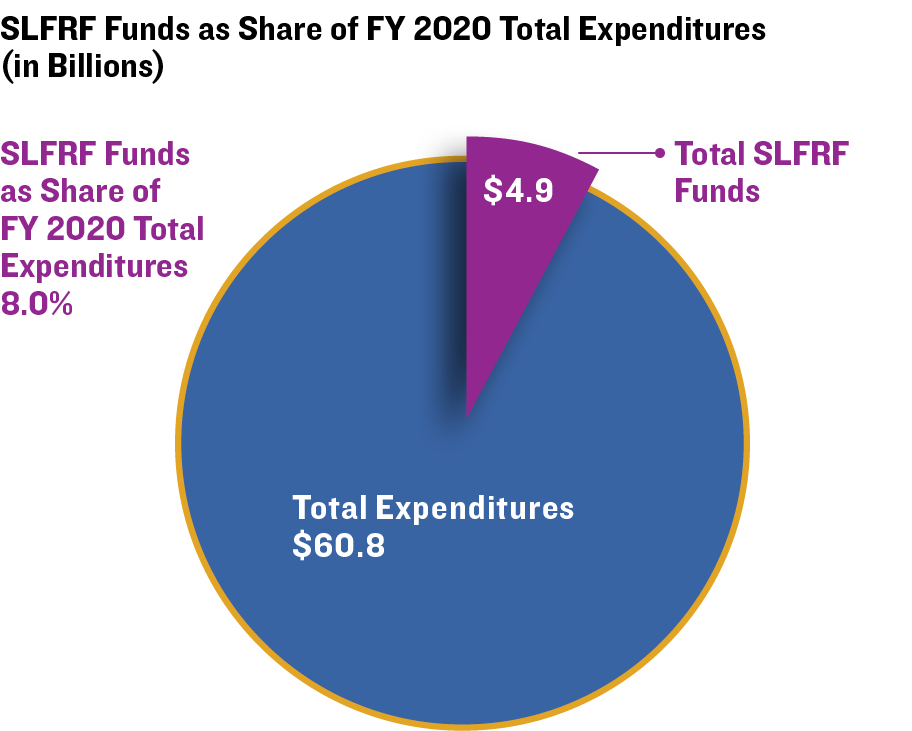

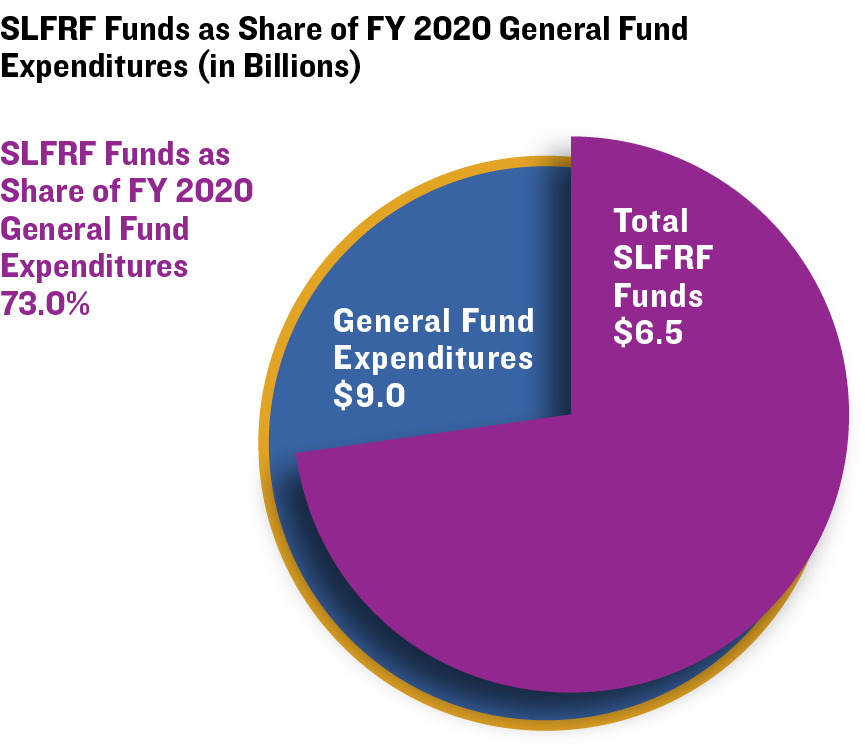

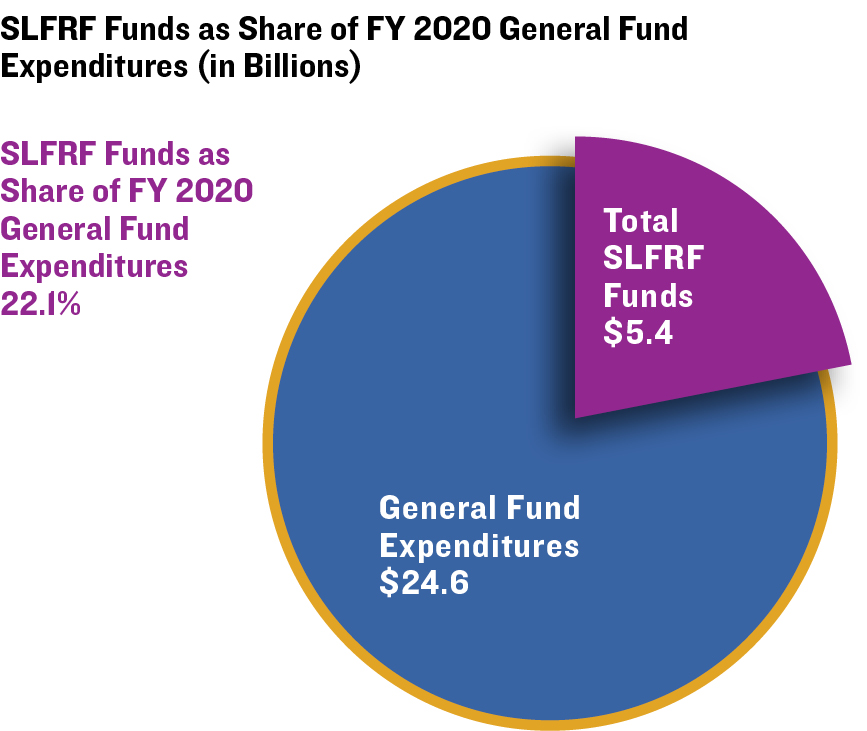

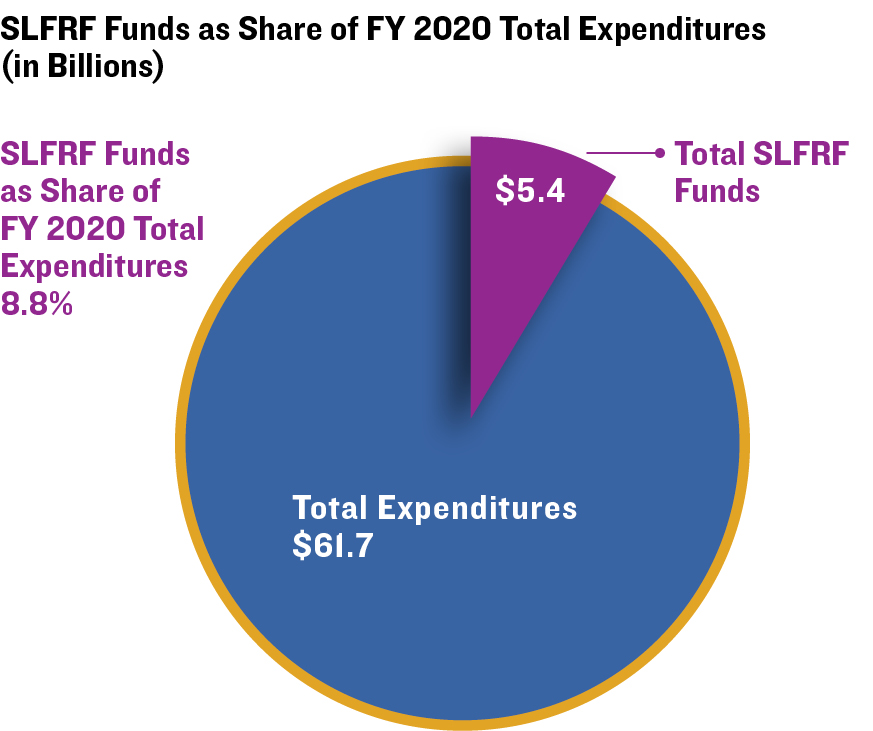

As of July 30, 2021, the portion of funds that these states had allocated to specific expenditure categories ranged from 0 percent in New York, North Carolina, and Texas to 63 percent in Pennsylvania and close to 100 percent in California (table 3). Six states received all their SLFRF payments in 2021; five received half of their funds in 2021 and will get the rest in 2022. Total SLFRF allocations per state generally ranged from 17 percent to 26 percent of fiscal 2020 general fund expenditures (with one outlier, Michigan, at 73 percent) and 7 percent to 12 percent of total expenditures in fiscal 2020, including capital outlays.32 The median percentages were 22 percent of general fund expenditures and 9 percent of total outlays.

Planned Uses of SLFRF

The discussion of planned state uses of SLFRF is presented in three sections based on how much of a state’s total funds had been allocated or planned for as of July 31, 2021. (Data for Texas are based on a summary of a supplemental appropriations bill passed in October 2021.) The discussion starts with states that had allocated at least half of their SLFRF (California, Texas, Pennsylvania, Illinois, and Florida). The subsequent sections address states that had allocated about about 33 percent (New Jersey and Ohio) and those that had allocated less than 20 percent (Georgia, Michigan, New York, and North Carolina).

States that Have Allocated or Planned for over 50 Percent of Their SLFRF Money

CALIFORNIA

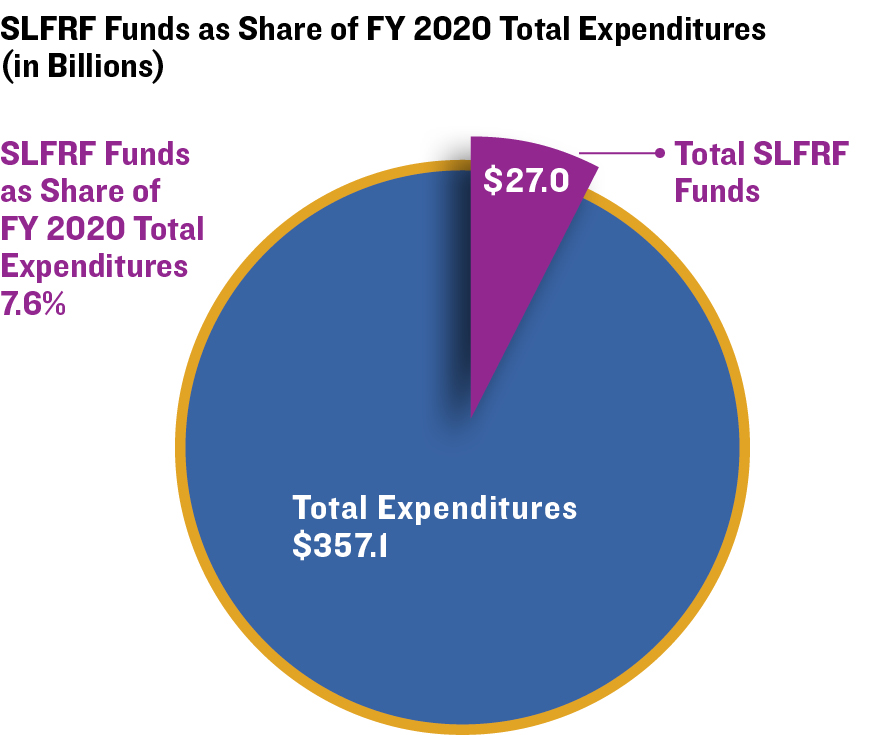

ARPA allocated $27 billion in relief funds to California. The amount is equivalent to about 19 percent of the state’s general fund expenditures and 8 percent of the state’s total expenditures, including capital, in fiscal 2020. California received its funds in one payment; it is the only state among the eleven states studied to allocate almost all its funds before submitting its first recovery plan to the Treasury in August 2021.33

California allocated about one-third of its SLFRF assistance ($9.1 billion) to capital projects. This includes $3.8 billion for broadband, $4.9 billion for affordable housing, and $450 million for community care expansion, such as beds for seniors and other adults with disabilities. Capital projects involve one-time spending but may require future funding of associated operations and maintenance.

The state also designated SLFRF dollars to programs that appear to be addressing short-term needs. These include assistance to small businesses ($1.5 billion), a program for water and utility arrearages ($2 billion), and education and training grants for displaced workers ($472 million).

California is using a significant portion ($8.9 billion) of its SLFRF for revenue replacement in the general fund. This could lead to a fiscal cliff if the money is used to finance recurring costs and revenues are not sufficient to cover those costs in the future.34 These SLFRF dollars are listed in both the state recovery plan and the California fiscal 2022 budget as a lump-sum amount, with no indication of how they will be spent.

A 2022 budget overview report released by the Legislative Analyst’s Office says the California legislature had a surplus of about $47 billion to allocate in the 2022 budget because revenues exceeded estimates in fiscal 2021.35 The report estimates that about $39 billion of the surplus was allocated to one-time or temporary programs; $3.4 billion was used for new, ongoing programs; and the rest was put in reserves or used for debt or other liabilities. It says the full implementation of the recurring commitments will be $12.4 billion by 2025–26.36

A 2022 budget overview report released by the Legislative Analyst’s Office says the California legislature had a surplus of about $47 billion to allocate in the 2022 budget because revenues exceeded estimates in fiscal 2021.35 The report estimates that about $39 billion of the surplus was allocated to one-time or temporary programs; $3.4 billion was used for new, ongoing programs; and the rest was put in reserves or used for debt or other liabilities. It says the full implementation of the recurring commitments will be $12.4 billion by 2025–26.36

Some of the other uses of SLFRF identified in California’s recovery plan could also result in recurring spending. For example, the state’s Child Savings Account program ($1.8 billion), which helps low-income students set goals and save money for higher education, appears to address an ongoing need. California is also investing $530 million to expand access to behavioral health services. The pandemic has intensified the need for such services, but the recovery plan notes that the need was rising before the pandemic. In addition, the state is allocating funds to workforce training and mentoring efforts, such as the Community Economic Resilience program ($600 million), that may remain in demand beyond the availability of SLFRF support.

California's use of SLFRF for capital projects and other one-time or short-term programs is consistent with its average A grade in budget maneuvers for fiscal 2015–19. However, the state has also allocated a significant portion of its funds as a lump sum to the general fund and for uses that may have recurring expenditures. This could necessitate increased state funding or program cuts to avoid a future shortfall.

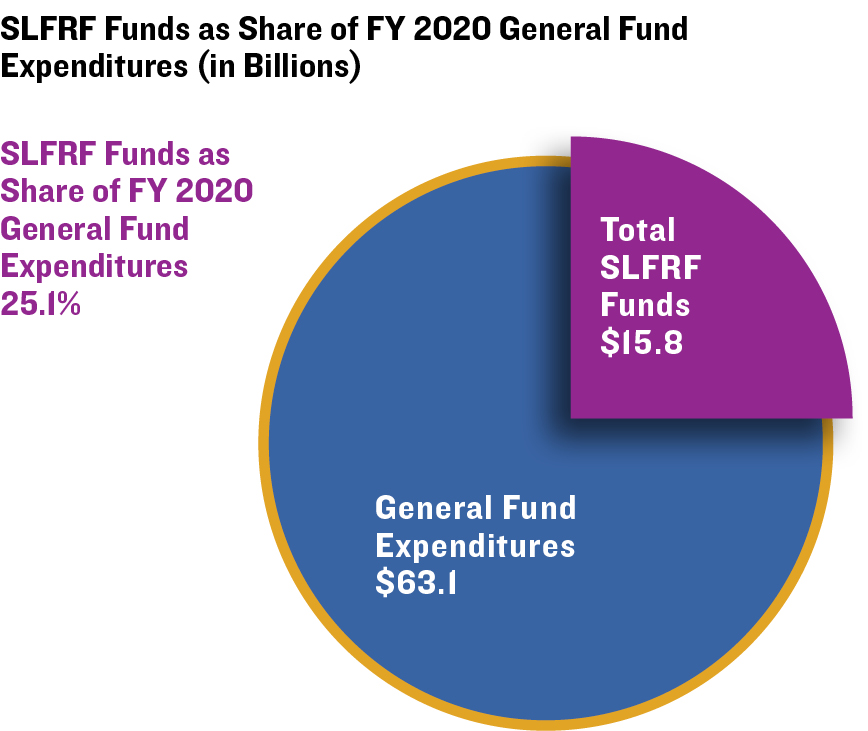

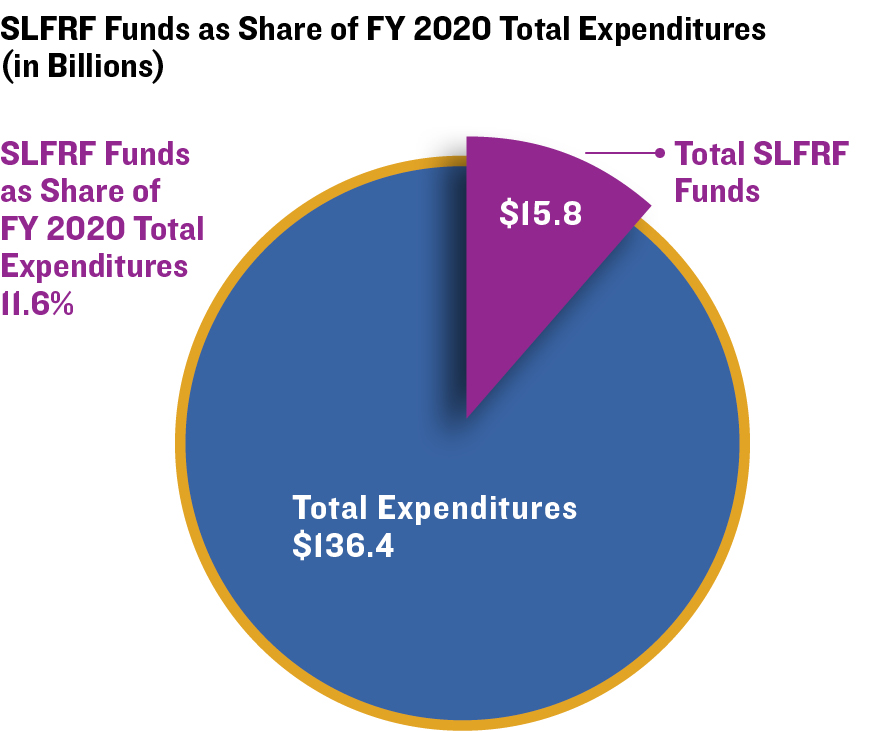

TEXAS

Texas received its $15.8 billion in SLFRF in one payment. This amount is equivalent to about 25 percent of the state’s general fund expenditures and 12 percent of its total expenditures, including capital outlays, in fiscal 2020. The legislature passed a supplemental appropriations bill in October 2021 that allocated $12.8 billion, or 81 percent of the state’s SLFRF, plus $500.5 million from the Coronavirus Capital Projects Fund, another component of ARPA. The information presented in this section is based on a summary of the bill released by a Texas senator who sponsored it. (Texas’s initial recovery plan, submitted to the Treasury in August 2021, did not describe how the funds would be allocated.38)

Texas plans to put much of its SLFRF assistance toward one-time uses. It allocated $7.2 billion to repay federal advances for the state’s unemployment insurance trust fund and replenish it to the statutory floor, which is defined as 1 percent of taxable wages.39 Texas also designated almost $900 million for capital projects. This includes funding for higher education projects, contingent on passage of legislation ($325 million); a state operations center to aid in disaster response ($300 million); completion of a new psychiatric hospital ($238 million); and improvements in filtration and ventilation systems at veterans’ homes ($35 million). The construction of new facilities will require future spending on operations and maintenance.

The state is also investing in upgrades to systems, including enhancements to cybersecurity ($200 million); modernization of the Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program ($25 million); and information technology improvements for Children’s Advocacy Centers ($1.2 million).

The other planned uses of SLFRF primarily address short-term needs. They include $2.4 billion for health care staffing, therapeutic drugs, and support for regional infusion centers, and $286 million for state-administered health care programs for retired and active educators. The latter amount is designed to cover COVID-related health claims and prevent pandemic-related increases in teacher and retiree health care premiums. The state is also allocating funds to support the tourism industry ($200 million) and food banks ($100 million).

The state’s appropriations also appear to address ongoing needs, including cash for organizations assisting victims of sexual assault and other crimes ($160 million) and programs to expand mental health treatment options for young people ($113 million).

Overall, most of Texas's appropriations of SLFRF are for health care and one-time uses. This is consistent with its B average grade in budget maneuvers for fiscal 2015–19. Texas will need to ensure that it has sufficient revenues to cover operating and maintenance costs associated with new capital facilities, however.

PENNSYLVANIA

Pennsylvania received its $7.3 billion of SLFRF in one payment. The funds are equivalent to about 20 percent of the state’s general fund expenditures and 8 percent of its total expenditures, including capital outlays, in fiscal 2020. The state’s first recovery plan discussed the use of about 63 percent of those funds, and all of that was dedicated to revenue replacement.

Pennsylvania’s fiscal 2022 budget appropriated $4.6 billion from SLFRF. The largest component, $3.8 billion (83 percent of allocated funds), was transferred to the general fund to help pay for services.40 Although the money does not appear to be tied to specific outlays, Pennsylvania’s recovery plan describes components of the general fund budget that grew significantly, including a $2.5 billion rise in the Department of Human Services budget. The increase was driven primarily by growth in the state’s Medicaid program, called Medical Assistance; $300 million for the Basic Education subsidy to school districts; and gains in other education programs ($30 million for early learning, $11 million for early intervention preschool services, and $50 million for special education subsidies to school districts). State health care centers and local health departments also received more funding. Although some of the health-related spending might be temporary, depending on the pandemic, education needs are likely to continue.

Other major components of Pennsylvania’s SLFRF allocation in the fiscal 2022 budget appear to address temporary or one-time spending. This includes $372 million to create and retain jobs and provide other assistance in areas hit hard by the pandemic and $282 million for nursing home facilities, assisted living facilities, and personal care homes. The latter amount can be used to support pandemic-related costs, premium pay, and improvements to air quality controls in facilities to prevent the spread of disease, as well as to offset revenue losses. The state has also allocated $50 million to provide additional funds for affordable housing. Pennsylvania appears to be putting some of its SLFRF support toward ongoing needs, which may present fiscal challenges after those funds are no longer available.

The use of one-time SLFRF funds to finance recurring spending is consistent with Pennsylvania’s D-minus average grade in budget maneuvers for fiscal 2015–19.

ILLINOIS

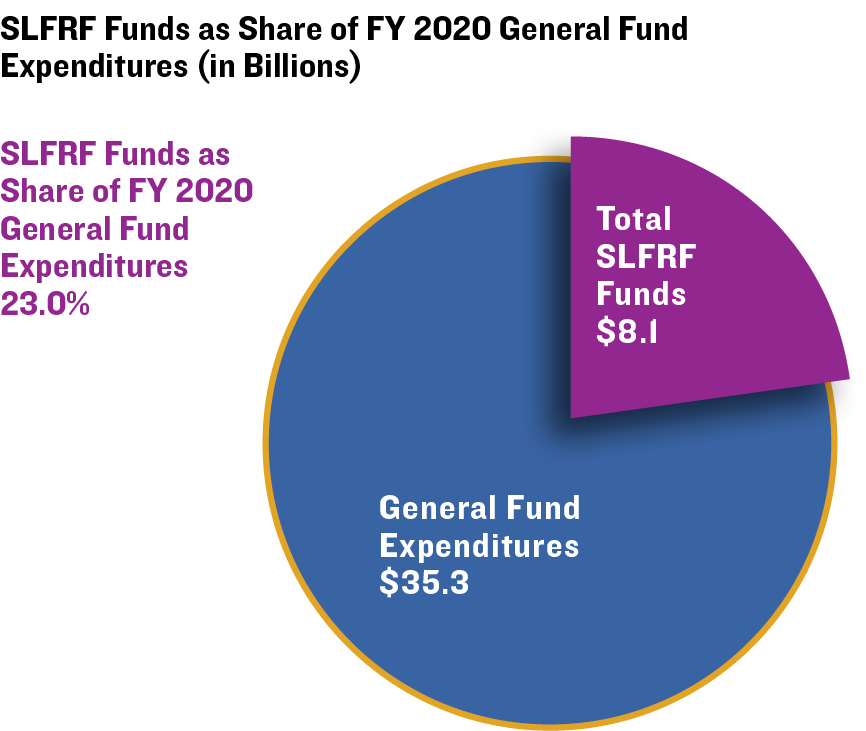

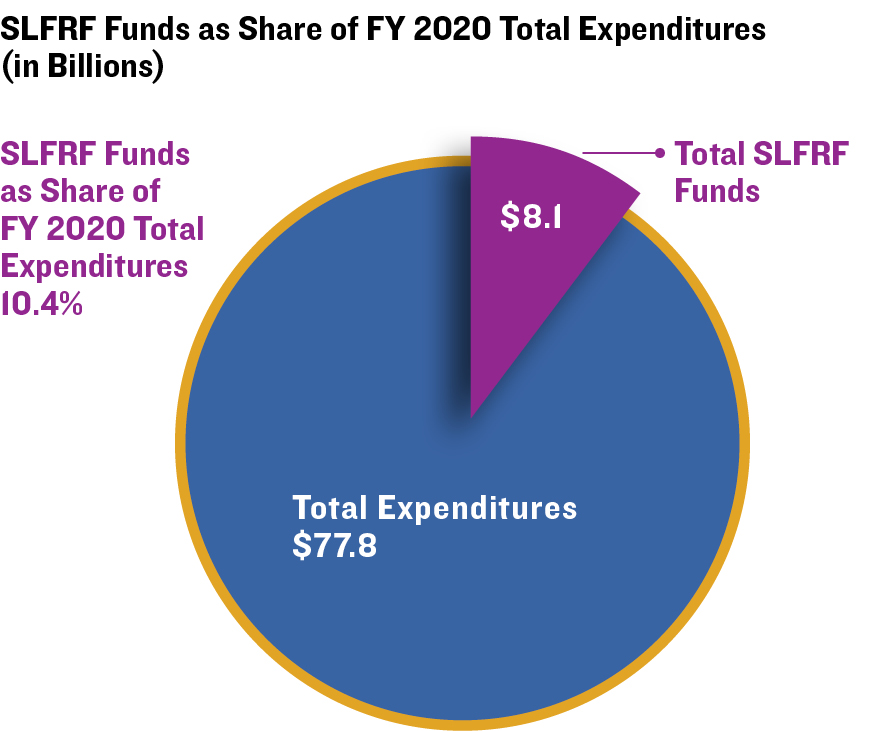

Illinois received $8.1 billion in SLFRF funds, which is equivalent to about 23 percent of the state’s general fund and 10 percent of its total expenditures, including capital outlays, in fiscal 2020. All funds were received in one payment. According to the state’s first recovery plan, the fiscal 2022 budget includes $2.8 billion in initial SLFRF appropriations.41

A press release on the fiscal 2022 budget from the governor’s office described those appropriations, as well as $2 billion–$3 billion in reserved ARPA funds “to replace lost revenues to the State to fund essential government services.”42 The general funds revenue statement in the fiscal 2022 budget summary report shows a $2 billion line item labeled “ARPA Reimbursement for Essential Government Services,” but it does not disclose how those funds will be used.43 (The state recovery plan does not mention them.) If the reserves are included, Illinois has allocated 59 percent of its total SLFRF; if not, the state has allocated 35 percent.

The state recovery plan notes that the $2.8 billion SLFRF appropriations include $1 billion for water, sewer, and broadband infrastructure and $1.8 billion for operational spending. The operating funds comprise $786 million for health-related costs, including $280 million for long-term care services, mental health rehabilitation facilities, and hospitals; and $258 million to agencies for personal protective equipment, alternative care sites, and increased operating costs. Illinois also allocated $424 million for financial assistance to hard-hit industries and small businesses.

Some of the state’s appropriations appear to address needs that could outlive SLFRF. They include funds to areas such as trauma, mental health, and behavioral health ($50 million); to community support organizations ($147.3 million, including $87 million for centers that assist immigrants and refugees); to Criminal Justice Information Authority violence prevention and interruption programs ($55.8 million); and to Illinois State Board of Education enrichment activities and parent mentoring (no dollar amount specified).

Illinois has a potential for a fiscal cliff if it uses a portion of the SLFRF appropriations or reserves to pay for recurring spending.44 Its history of using one-time revenue sources to finance recurring needs led to the state’s D average grade, the second-lowest mark, in budget maneuvers for fiscal 2015–19.

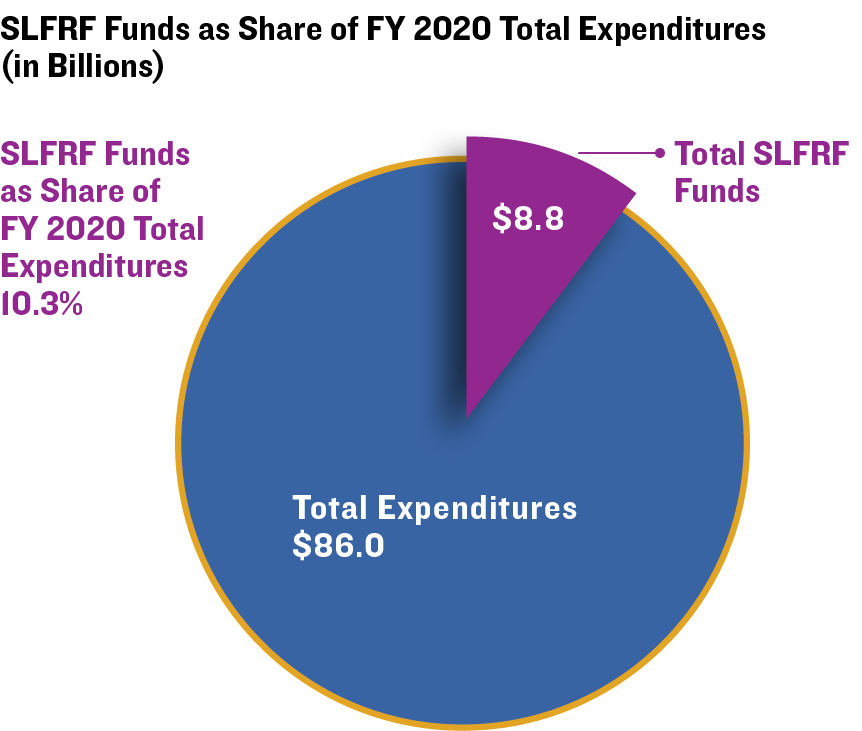

FLORIDA

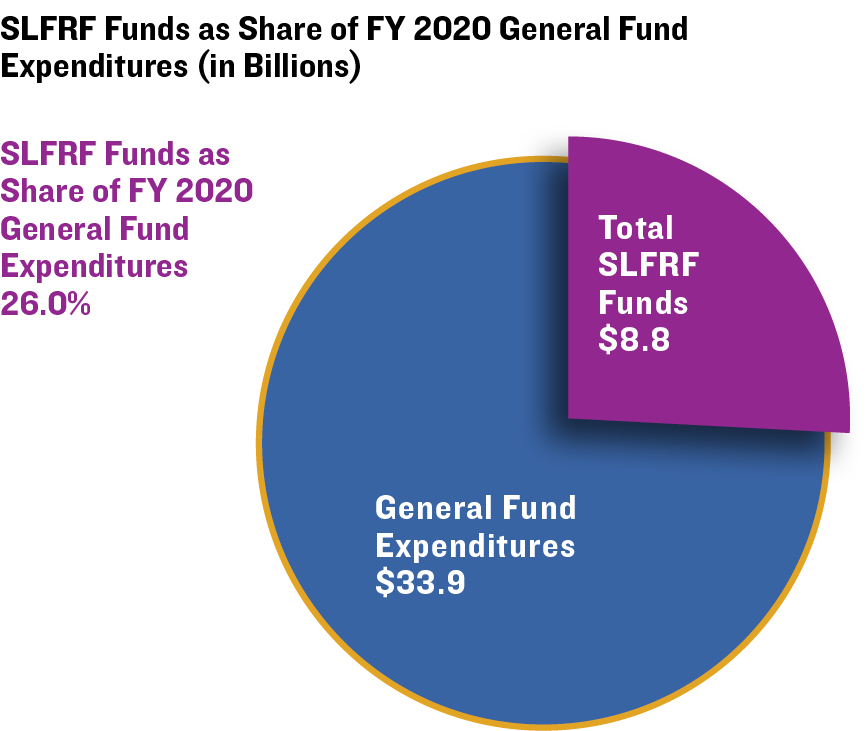

Florida’s share of SLFRF support is $8.8 billion, which is equivalent to about 26 percent of the state’s general fund expenditures and 10 percent of its total fiscal 2020 expenditures, including capital outlays, in fiscal 2020. The state received its first SLFRF payment in 2021 and will receive a second in 2022. The legislature appropriated the full first payment in its fiscal 2022 budget.

The state’s largest planned use of SLFRF cash as of July 2021 was for capital projects, including clean water infrastructure ($1.5 billion), state highway system capital projects ($1.4 billion), and deferred building maintenance ($287 million).45 Florida also plans to use SLFRF for other capital projects, including higher education facilities ($156 million), an emergency operations center ($82 million), two new armories ($41 million), grants for African American cultural and historical facilities ($25 million), and funding for infrastructure for rural school districts with high poverty rates and small property tax bases ($172 million). Some of these projects, especially those involving new construction, will require funding for future operation and maintenance costs.

Florida has identified other one-time spending. This includes premium pay for first responders ($208 million) and modernizing the state’s reemployment systems ($46 million) and workforce information system ($82 million). Florida identified premium pay as a use under revenue replacement rather than under the federal premium pay expenditure category.

Most of the other funds from the first payment will be used for economic recovery, including programs to encourage growth and resiliency in underserved communities ($41 million), assistance to ports ($250 million), and programs to rebuild the tourism industry ($20 million). The state also plans to invest in the New Worlds Reading Initiative ($102 million), which provides home-delivered books for elementary students reading below grade level.

The reading program may be addressing a recurring need, and the capital investments are likely to have future operations and maintenance costs. Most other planned uses for SLFRF appear to be for one-time or temporary investments, which is consistent with its average B grade in budget maneuvers for fiscal 2015–19.

States that Have Allocated or Planned for About 33 Percent of Their SLFRF Money

New Jersey

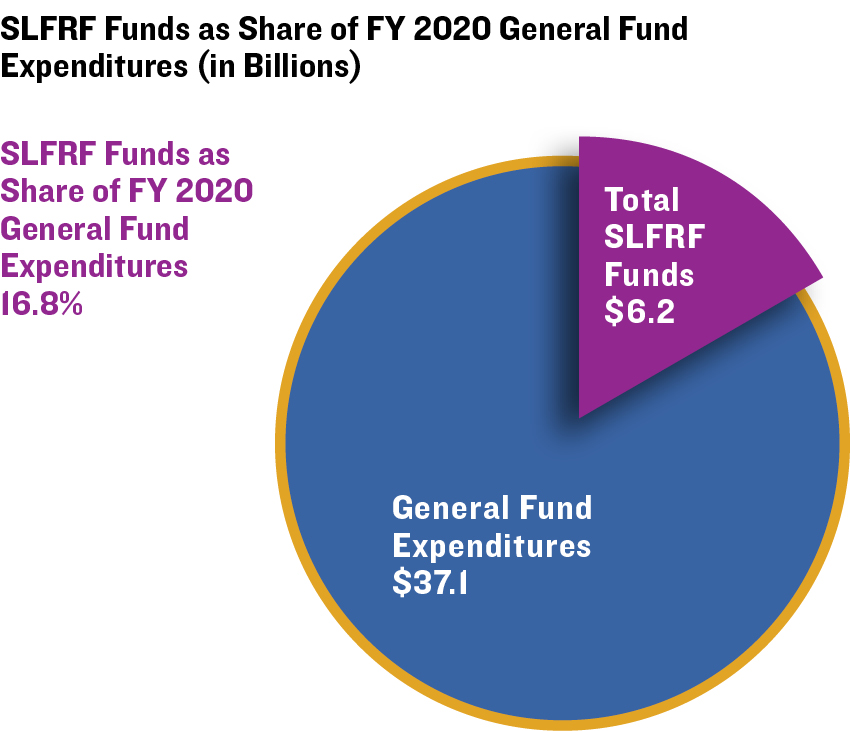

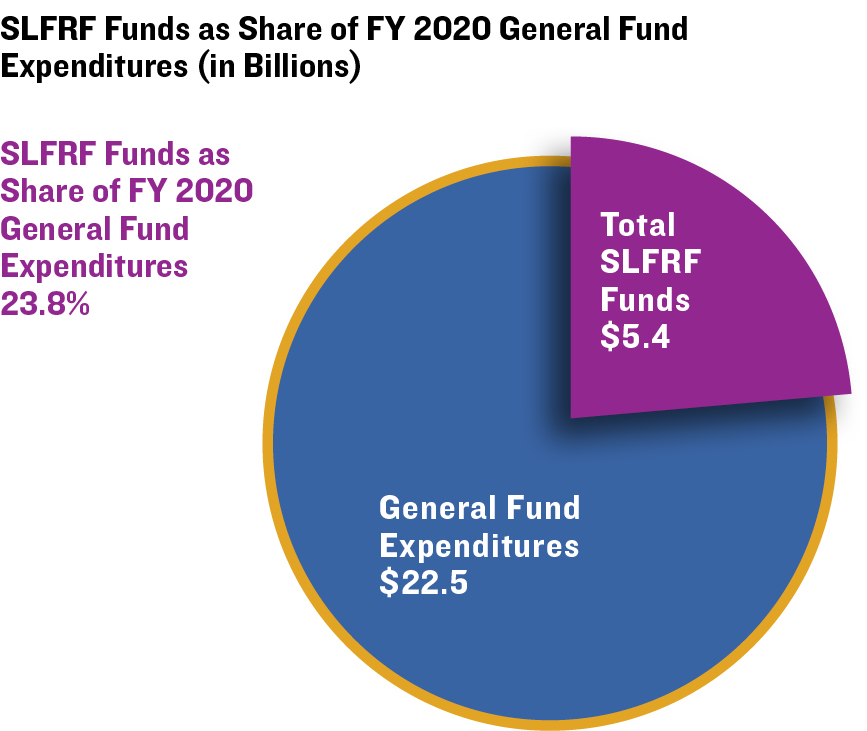

New Jersey received its $6.2 billion in SLFRF assistance in one payment. This is equivalent to about 17 percent of the state’s general fund expenditures and 9 percent of its total expenditures, including capital outlays, in fiscal 2020. The initial recovery plan submitted to the Treasury discussed plans for allocating about 38 percent of those funds.

The state has designated about 31 percent ($739 million) of the allocated SLFRF for capital projects.46 This includes investments in trauma centers ($450 million); heating, ventilation, air-conditioning, and water system improvements financed through the School and Small Business Energy Efficiency Stimulus Program ($180 million); long-term facility upgrades financed through the Child Care Revitalization Fund ($55 million); water projects ($44 million, including $5 million for cybersecurity); and residential lead paint remediation ($10 million). The trauma centers will probably have operation and maintenance spending needs, but most of the other capital projects appear to be improvements to existing facilities. New Jersey is also investing in modernizing its unemployment processing system ($10 million).

New Jersey has targeted a portion of the remainder of the first SLFRF installment to provide aid to businesses and individuals. The business allotment includes funding for the Small Business Relief Grant program ($135 million), Commuter and Transit Bus Private Carrier Pandemic Relief and Jobs Program ($25 million), and the Meadowlands complex ($15 million). The largest assistance for individuals is the Eviction Prevention Program ($750 million), which provides help with rent and utility bills.

The biggest program that appears to address a continuing need is a special education effort for students who are above the normal age of eligibility. Recognizing that these students have been adversely impacted by the pandemic, the state appropriated $600 million to cover funding for the next three school years. It also increased state funding for special education in the fiscal 2022 budget.47 There may be pressure to continue the services for students older than the normal age beyond the three-year period. New Jersey also is financing with SLFRF money several smaller programs that may relate to ongoing needs.

Although New Jersey’s consistent use of one-time revenues and similar solutions to achieve balance yielded a D average in budget maneuvers for fiscal 2015–19, most of the state’s allocation of SLFRF as of July 2021 appears to be for one-time or temporary programs.

Ohio

Ohio was given $5.4 billion in SLFRF assistance, with half received in 2021 and the other half scheduled in 2022. The payments are equivalent to about 24 percent of the state’s general fund expenditures and 7 percent of its total expenditures, including capital outlays, in fiscal 2020. Ohio’s first recovery plan submitted to the Treasury identified plans for spending about 34 percent of its SLFRF cash.

Most of those funds will be used for one-time spending. The largest planned use is for repaying a $1.5 billion federal loan to the state unemployment insurance trust fund. The state recovery plan indicates that this will prevent large federal unemployment tax increases that might discourage businesses from hiring and investing.48

Ohio also plans to spend $250 million for water and wastewater capital projects and $84 million to increase capacity at its pediatric behavioral health hospitals. The hospital expansions and at least some water or wastewater projects are likely to require funds for future operations and maintenance.

Ohio’s planned use of SLFRF for one-time spending is consistent with its average grade of B in budget maneuvers for fiscal 2015–19.

States that Have Allocated or Planned for Less than 20 percent of Their SLFRF Money

Georgia

Georgia received $4.9 billion in SLFRF support—half in 2021 and half in 2022. The total amount is equivalent to about 17 percent of the state’s general fund expenditures and 8 percent of its total expenditures, including capital outlays, in fiscal 2020. In its first recovery plan submitted to the Treasury, Georgia disclosed spending plans for about 18 percent of SLFRF.

The state plans to award funding via three facilities: a broadband infrastructure competitive grant program ($300 million); a water and sewer infrastructure competitive grant program ($250 million); and a negative economic impact competitive grant program

($325 million),49 which will focus on recovery in the hardest-hit industries and demographic groups. Georgia has established program committees, made up of legislators and leaders of state agencies, to review, evaluate, and make recommendations to the governor on grant awards. The governor’s Office of Planning and Budget will help coordinate the process.

Although Georgia had not allocated SLFRF money to the public health category as of July 21, 2021, its recovery plan indicated that the state planned to provide up to $25 million to the State Health Benefit Plan to offer vaccine incentives for state employees and teachers.

The use of SLFRF for one-time grants and vaccination incentives is consistent with Georgia’s A average in budget maneuvers for fiscal 2015–19.

Michigan

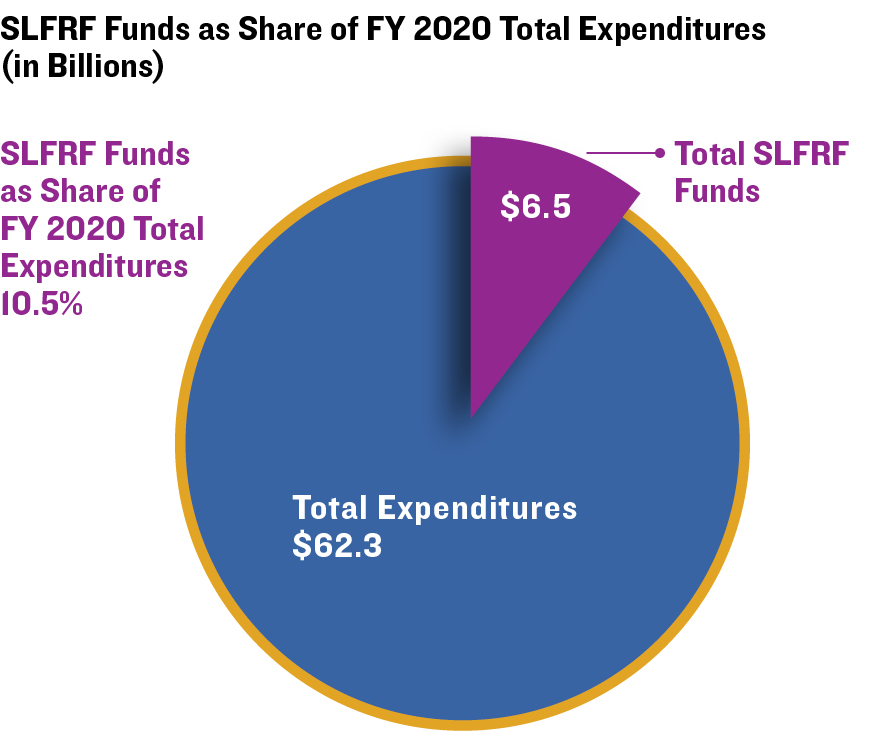

Michigan will receive $6.5 billion from the SLFRF program in 2021–22. This is equivalent to about 73 percent of the state’s general fund expenditures and 11 percent of its total expenditures, including capital outlays, in fiscal 2020. The first recovery plan that Michigan submitted to the Treasury detailed allocation plans for only 7 percent of its SLFRF dollars.

Of the states studied, Michigan is the only state to detail criteria for allocating SLFRF cash. They include sustainability and a program’s ability to address issues created by the COVID-19 pandemic. Under sustainability, the state will seek to determine a program’s estimated return on investment and any requirement for ongoing support. Criteria include equity, the transformational nature, leverage, efficacy, and sufficient support and capacity to implement programs.50

Michigan will apply a portion of its SLFRF receipts to one-time purposes. The state designated $75 million for grants to school districts to address one-time strategic investments in infrastructure or equipment—such as heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning systems—needed to operate schools year-round. The timeline for this program is September 1, 2021, through June 2023. To address negative economic impacts, Michigan allocated $160 million to hospitals and $100 million to long-term care facilities. The timeline for both those programs was August 1, 2021, through December 2021.

The state is allocating $121 million to expand the number of four-year-old, low-income children served by the Great Start Readiness Program, which helps improve readiness and subsequent achievements of educationally disadvantaged children. The timeline for this funding is September 1, 2021, through August 2022.

The emphasis on the sustainability of programs and the disclosure of a timeline for short-term programs are consistent with Michigan’s B average in budget maneuvers for fiscal 2015–19.

New York

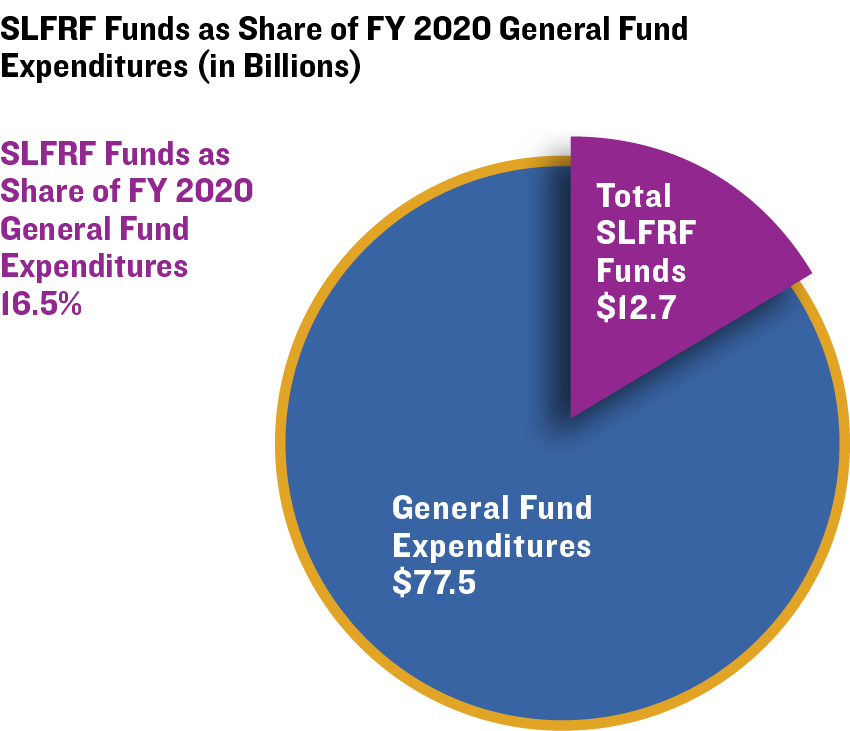

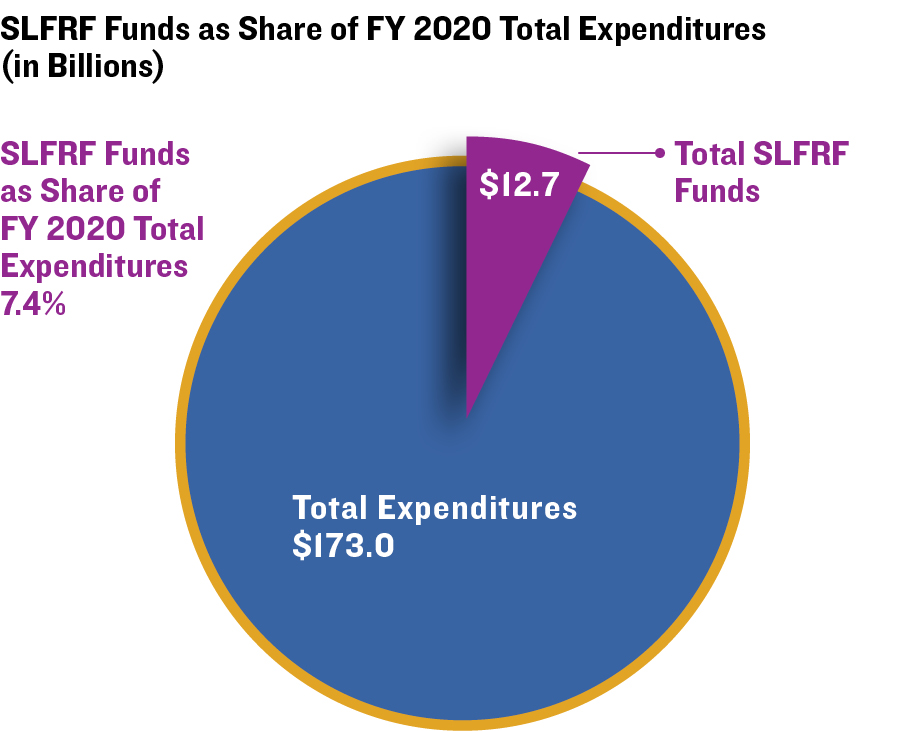

New York received its $12.7 billion in SLFRF assistance in one payment. This is equivalent to about 17 percent of the state’s general fund expenditures and 7 percent of its total expenditures, including capital outlays, in fiscal 2020. Its fiscal 2022 Enacted Budget Financial Plan shows an allocation of the SLFRF receipts over four years.51 The allocation for fiscal 2022 is $4.5 billion, or 35 percent of New York’s total, though the financial plan does not specify how that money will be used.

The state’s initial recovery plan indicates that the governor and the Division of the Budget in the executive branch will work with state agencies to develop programs to help low-income renters and homeowners, small businesses, and the hardest-hit sectors of the economy, including restaurants and tourism.52 The plan discusses programs under consideration but does not provide information on dollar amounts.

New York is also exploring using SLFRF to support its affordable housing initiative, which focuses on residential creation, preservation, and supportive services. Assistance for rental and utility arrears and temporary rental assistance may also be considered, as well as grants or low-interest loans to small businesses and independent arts and cultural organizations. In addition, the recovery plan discusses the possibility of providing free legal services and information to commercial tenants and small-business landlords to renegotiate leases.

The plan identifies community safety as a priority, noting that New York views gun violence as a public health crisis. SLFRF may also be earmarked for workforce training and job placement programs in the twenty cities most affected by gun violence, first responder training to decrease bias, educational programs, and increased green space to encourage community activities and engagement.

New York received a D average in budget maneuvers for fiscal 2015–19. Some SLFRF-backed programs the state is looking at involve one-time or short-term appropriations; others, such as the investment in programs to decrease gun violence and housing supportive services, appear to be addressing continuing needs.53

North Carolina

North Carolina was allocated $5.4 billion in SLFRF dollars, equivalent to about 22 percent of the state’s general fund expenditures and 9 percent of its total expenditures, including capital outlays, in fiscal 2020. The state received half the funds in 2021 and will receive the other half in 2022.

The state’s first recovery plan submitted to the Treasury said that spending decisions were not expected to be made until fall 2021.54 North Carolina began its fiscal year July 1, 2021, without a fiscal 2022–23 biennial budget; the governor finally signed the measure in November. Although little information was available at the time this paper was prepared, the Carolina Journal website reported that the budget included $1 billion in new federal funding for broadband expansion.55

North Carolina received a B average grade in budget maneuvers for fiscal 2015 through 2019.

Use of SLFRF Relative to Truth and Integrity in State Budgeting Grades

Initial allocations of SLFRF by the largest states show significant uses for one-time spending, primarily capital projects and unemployment trust fund loan repayments, but some states have also dedicated funds to programs that appear to require recurring expenditures. This section summarizes the findings on the initial spending plans for SLFRF receipts, including whether recovery plans are consistent with the average grades in the budget maneuvers category for fiscal 2015–19 in the 2021 Truth and Integrity in State Budgeting study.

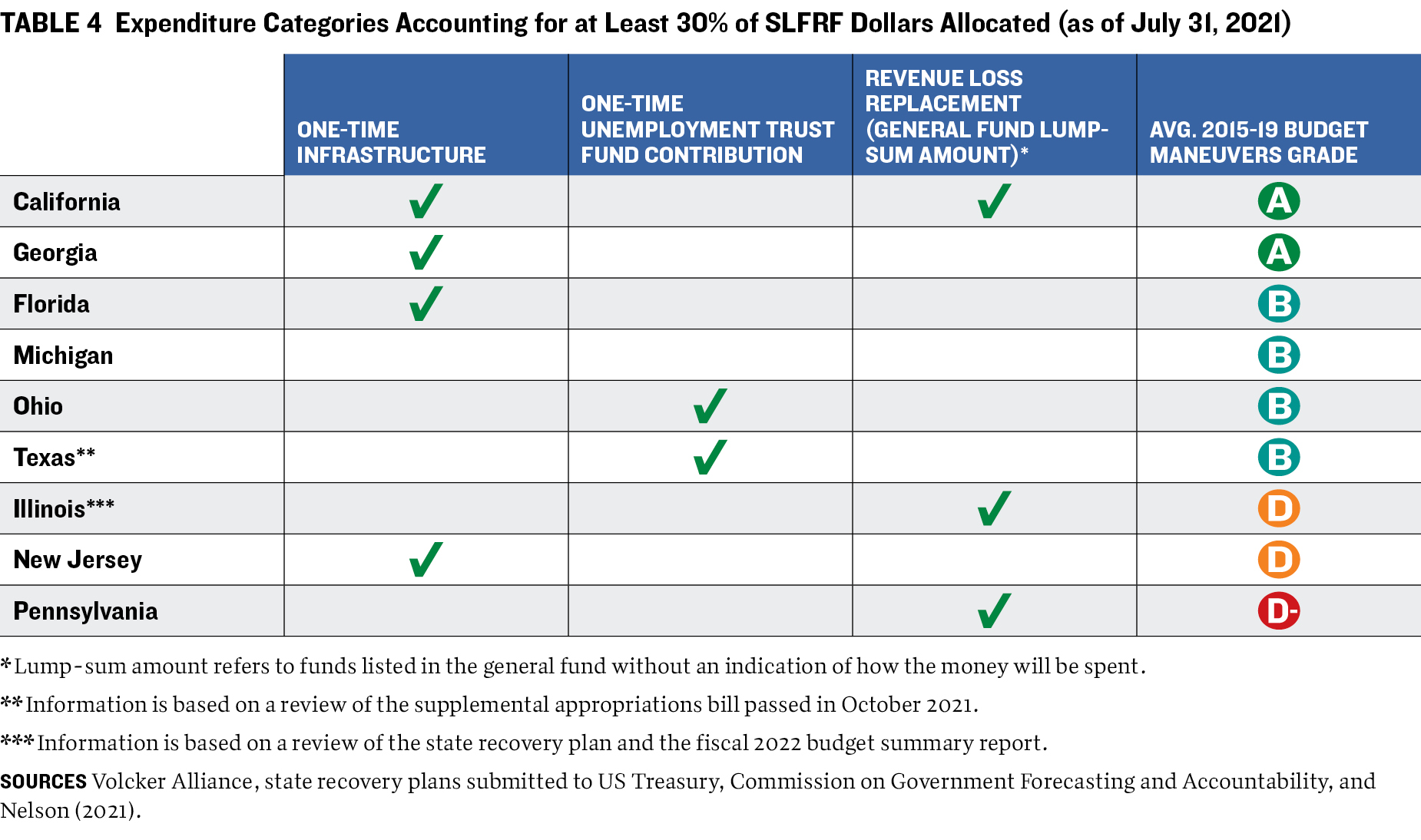

Four of the nine largest states for which information is available have allocated at least 30 percent of their planned use of SLFRF to infrastructure or capital projects (table 4). These include California and Georgia, which received A averages; Florida, with a B average; and New Jersey, with a D. Capital investment represents one-time spending, which is appropriate for the use of one-time federal funds. These projects will also continue to provide benefits. Depending on the nature of the capital investment, however, states may need to identify future general fund or other resources for maintaining and operating projects.

Two of the largest states have allocated SLFRF money to contribute to their unemployment trust funds to repay federal advances. Texas dedicated $7.2 billion and Ohio $1.5 billion for this purpose. Such loan payments are one-time actions consistent with the B average both states received in budget maneuvers.

As of December 31, 2021, nine states and one territory owed $39.9 billion on federal unemployment trust fund loans. The states with the largest advances included California ($19.6 billion), Illinois ($4.5 billion), and New York ($9.3 billion).56 California won an A average in the category, while Illinois and New York, reflecting a history of using one-time actions to achieve budgetary balance, garnered D averages. In March 2022, Illinois passed legislation authorizing the use of SLFRF to repay $2.7 billion in unemployment trust fund loans.57

Several of the states studied are investing SLFRF grants into one-time systems improvements, with Florida modernizing its reemployment and workforce information programs and Texas bolstering cybersecurity. These types of outlays can help prepare the state for future emergencies or decrease risks.

In contrast, five states have designated at least 10 percent of their initial SLFRF allocations to programs that may be addressing recurring needs. California, Pennsylvania, and Illinois put a significant portion of their SLFRF receipts into their general funds in lump sums. However, Michigan and New Jersey are funding specific programs with timelines showing that they intend their SLFRF-financed programs to be short-term.

Overall, the initial allocation of SLFRF money appears consistent with budget maneuvers grades for individual states, with two exceptions: New Jersey has a low average grade but plans primarily to finance one-time capital projects and short term programs in its initial allocation of federal dollars, while California has a high budget maneuvers grade but may be using SLFRF allocations to finance recurring general fund spending.

SLFRF reporting Transparency

In the Volcker Alliance’s Truth and Integrity in State Budgeting (2021), California won an A average grade in transparency for fiscal 2015–19, while the other ten states studied in this report received Bs. Despite that performance, these states need significantly more disclosure of information about SLFRF.

This section provides an assessment of transparency issues related to disclosures of SLFRF use. We examine whether the eleven states clearly reported SLFRF allocations as one-time funds, whether they effectively presented the use or planned use of the money, and how they shared information about the amounts of appropriations and spending.

State Budget Documents

The timing of ARPA’s passage in March 2021, followed by the Treasury’s release in May of its interim final rule for implementing SLFRF, created appropriation and reporting challenges for states that were in the final stage of passing their fiscal 2022 budgets. (In forty-six states, the fiscal year begins July 1.58)

The states we studied handled these challenges in different ways. California appropriated all its SLFRF money in its fiscal 2022 budget, while Ohio and Texas (with fiscal years beginning September 1) chose not to appropriate any SLFRF payments in their main budget bills. Florida appropriated an estimate of its first SLFRF payment and later prorated the amount assigned to programs to match the actual allotment.59 Michigan, where the fiscal year starts October 1, appropriated funds in its 2021–22 omnibus budget bill and two prior appropriations bills.

The varied approaches can make it difficult to identify which pieces of legislation contained appropriations of the federal funds. The Michigan Senate Fiscal Agency, for example, provided an analysis that showed the amount of funds appropriated in the state’s general omnibus appropriations bill, as well as the two previous appropriation measures.60 Other states did not make such disclosures.

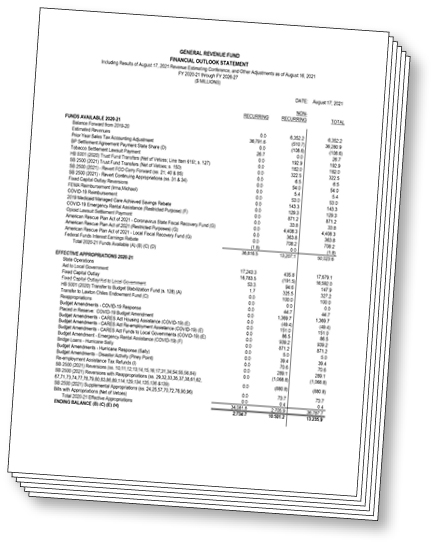

Another transparency issue is whether states clearly label the federal assistance as one-time funds. A review of fiscal 2022 state budget summaries identified Florida as the only one of the eleven studied to identify all SLFRF payments as one-time funds. Florida lists Coronavirus State Fiscal Recovery Funds in the column for nonrecurring revenues and appropriations in its general revenue fund financial outlook statement.61

Illinois and Pennsylvania provide only some disclosure about the one-time funds. Their budget documents list the portion of SLFRF assistance designated as a lump sum in the general fund as a separate revenue line item below estimated base revenues. This emphasizes that those payments are not part of recurring revenues, but the other SLFRF assistance being used to finance specific projects or services is not included in those figures.

New York’s fiscal 2022 Enacted Budget Financial Plan shows the SLFRF assistance as a general fund receipt titled “Federal Aid (Non-Tax Transfer).” The plan, which covers the current fiscal year and three additional years, details total SLFRF payments as $4.5 billion in fiscal 2022, $2.4 billion in 2023, $2.3 billion in 2024, and $3.6 billion in 2025.62 While this multiyear disclosure increases transparency, the plan does not indicate how the SLFRF dollars will be used.63

SLFRF receipts are less distinctly disclosed in other states’ general fund summaries. Some show various types of federal revenues, but it is not clear whether or where SLFRF money is included.

States also vary on how much information they provide about the use of SLFRF. For example, the summary of the enacted California fiscal 2021–22 budget gives a list of the projects and programs that will be funded with SLFRF. That list, however, includes $9.2 billion to “replace lost state revenue” but no breakdown of how that money will be used.64 Other states referred to broad categories for the use of the federal funds. For example, a Michigan Senate Fiscal Agency analysis included line items for Health and Human Services and Labor and Economic Opportunity under Federal Coronavirus State Fiscal Recovery Fund Appropriations.65 The Georgia fiscal 2022 appropriations bill recognizes $4.7 billion in SLFRF money and lists four categories (public health; premium pay; revenue replacement; and water, sewer, and broadband infrastructure) without providing dollar amounts for any.66

Several states provided information about how decisions were or will be made regarding SLFRF allocation. New Jersey’s budget document disclosed that the governor has the flexibility to spend up to $200 million with no one project exceeding $10 million. Spending above that must be approved by the six-member legislative Joint Budget Oversight Committee.67

Treasury Reports and Other Sources of SLFRF Information

State governments must disclose information related to the use of SLFRF receipts to the US Treasury, including an interim report that was due August 31, 2021, annual state recovery plans, and quarterly project and expenditure reports. States also must post their recovery plans to public websites when the reports are submitted to the Treasury.68

Each of the states studied posted an initial state recovery plan on a state website, with seven publishing it on the budget office site, three on a site created to show information on COVID-19, and one on the governor’s website. Using a web browser search to find the reports is challenging because of the lack of a standardized search term that works across states. The National Association of State Budget Officers developed a website with links to publicly available state recovery plans,69 but that site was still missing links for seven states several months after the submission deadline. Finally, in January 2022, the US Treasury provided the links for all state recovery plans and interim reports on a departmental site.70

The amount of information discussed in the initial state recovery plans varied. Among states studied, the length of the plans ranged from 4 pages (Texas) to 44 (California) and 143 (Florida). A plan’s length largely reflected how far along the state was in the process of allocating SLFRF money.

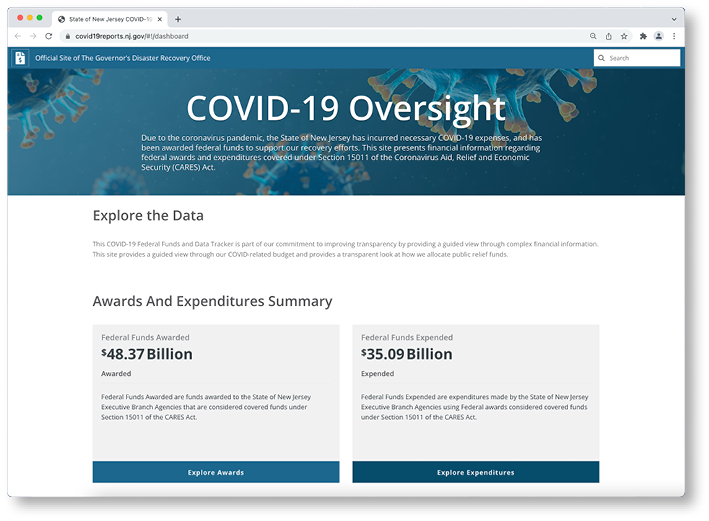

In addition to the federally mandated reports, some states have released documents or set up websites that are useful in understanding or tracking SLFRF and other ARPA funds (appendix A). The Illinois legislature, for instance, passed a statute creating a Legislative Budget Oversight Commission and requiring monthly and quarterly reports from the governor on state and local federal financial relief related to COVID-19.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Among the eleven states studied, revenue replacement was the largest category of planned spending as of July 31, 2021, accounting for 31 percent of allocated SLFRF dollars. (Among all states, nineteen allocated at least some funds to revenue replacement.) With some limitations, states have significant discretion on how this money may be spent.

The use of federal aid to replace lost revenue may create a fiscal cliff for some states once SLFRF money is spent by the deadline of December 31, 2026. That will, at least in part, depend on how the states use the funds. Three (California, Pennsylvania, and Illinois) of the eleven states studied allocated significant portions of their revenue replacement funds as lump-sum amounts to the general fund ($8.9 billion, $3.8 billion, and $2.0 billion, respectively). It is unknown whether the states will be able to replace these infusions. In contrast, Florida allocated its entire revenue replacement allocation to specific projects, most of which are one-time in nature (including $1.4 billion for highways). While Florida therefore has less risk of encountering a fiscal cliff, it could still better identify revenue sources to pay for operating and maintaining capital projects.

Further scrutiny of states’ use of SLFRF cash will be required. An assessment of the initial recovery plans for all fifty states found that only 43 percent of the federal support had been allocated as of July 31, 2021. Thirty-five states had allocated half or less of their total SLFRF allotment, and fifteen of those had not allocated for anything other than administrative costs. The timing of SLFRF receipts also invites further examination. Twenty states received half their money in 2021 and are scheduled to receive the remainder in 2022.

As states continue to make decisions about how to allocate their funds, they should consider the following recommendations to improve their long-term fiscal stability. These policy recommendations, and a second set on transparency, are based in part on best practices for avoiding one-time budget solutions identified in Truth and Integrity in State Budgeting: Preparing for the Storm and other Volcker Alliance reports and working papers. They include:

- drawing up plans to avoid fiscal cliffs when SLFRF dollars used to replace lost revenue are no longer available. These plans may involve limiting use of the funds to one-time or short-term programs, identifying new funding sources to sustain programs for the long term or when federal funding expires, or earmarking internal sources of revenue growth to support the programs;

- when tapping SLFRF for categories besides revenue replacement for programs with ongoing needs, clearly specifying their end date or identifying internal funding sources to sustain them once federal support runs out;

- identifying operating and maintenance expenditures of capital projects financed by SLFRF allocations, if applicable, along with ways to finance these costs from the general fund or other sources; and

- creating plans for spending SLFRF assistance over time and making them publicly available. States may find it helpful to do scenario planning and build flexibility into any plans they craft.

State governments should also consider bolstering disclosure practices for allocating and using SLFRF resources, including

- detailing SLFRF payments as nonrecurring in state budgetary financial outlooks and summary tables;

- implementing publicly available tracking systems that show how much of an SLFRF allotment has been received, allocated, appropriated, or spent;

- revealing how SLFRF allocation choices are being made and how much has been allocated to and spent on particular programs and services; and

- using performance metrics to assess whether SLFRF-financed programs are achieving their goals.

The Treasury, meanwhile, should continue to make state reports on the use of SLFRF publicly available. Although it issued revised guidelines for SLFRF reporting in November 2021,71 the department should also provide data from these disclosures in a format that can be downloaded and aggregated for research and analysis by policy analysts, scholars, and the public.

As states make decisions about allocating SLFRF money based on immediate local needs and priorities, they must also ensure fiscal sustainability and transparency. While the Treasury can play an important role in promoting better disclosure and public accountability by making information available to the public in a timely manner and a useful format, states themselves must ensure that $195.3 billion in emergency aid granted to them by Congress does not set them up for future fiscal shortfalls after the federal largesse ends.

APPENDIX A: How Six States Disclose Federal Pandemic Funding

Florida |

New Jersey |

|

General Revenue Fund Financial Outlook Statement shows federal COVID-19 funding and state appropriations of dollars received as nonrecurring |

Governor’s COVID-19 Oversight website discloses federal pandemic funding and spending |

|

|

Michigan |

New York |

|

House Fiscal Agency Fiscal Brief details ARPA aid to individuals, businesses, and the state |

State comptroller’s COVID-19 Relief Program Tracker website details programs funded by SLFRF and other federal actions |

|

|

Texas |

Illinois |

|

State comptroller’s infographic shows major ARPA components, and fund allocations |

SLFRF and other federal pandemic aid disclosed in governor’s reports to Legislative Budget Oversight Commission |

|

|

APPENDIX B: Research Methodology

The assessments in this paper are based on information obtained from the initial state recovery plans, fiscal 2022 state budget summary documents, and related sources. Categories used in this analysis are similar but not identical to the Treasury’s own expenditure categories. Our designation of infrastructure comprises allocations to water, wastewater, and broadband infrastructure but also plans for capital projects, such as roads and health facilities, that might be financed under different Treasury expenditure categories. Other one-time spending, including system improvements and replenishment of unemployment trust funds, may appear under the Treasury negative impacts category.

The research team used the following types or areas of spending to classify each state’s allocation of funds:

- Infrastructure

- System improvements

- Repayment of unemployment trust fund advances or replenishment of unemployment trust funds

- Premium pay

- Pandemic-related health care

- Assistance to businesses and individuals

- Pandemic-related workforce development

- Programs that appear to address recurring needs, such as education, mental health, behavioral health, and anti-violence programs

In figure 2, the first four types consist primarily of one-time spending. The next three are for programs that address needs that may decline if the pandemic and its economic impact wane. The last includes programs that appear to address a need that is likely to persist regardless of the status of the pandemic, as well as future operations and maintenance costs associated with capital facilities and infrastructure.

There are some gray areas, such as workforce development, that could relate directly to the pandemic or deal with an ongoing need, depending on the program. Similarly, programs to address issues like mental health or substance abuse may be needed more because of the pandemic but may exist beyond it.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This report was made possible in part by a grant from the Peter G. Peterson Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author. We acknowledge the formative leadership of the late Paul A. Volcker in increasing the breadth of research and focus given to state and local budgeting, both before the formation and as chairman of the Volcker Alliance. This work is continued by the Alliance, with the continuing support of numerous academics, government officials, and public finance professionals who inform the effort. We are also grateful to the National Association of State Budget Officers for its efforts in compiling Recovery Plan Performance Reports submitted by states to the US Treasury.

ENDNOTES

- Fiscal sustainability refers to a government’s ability to continue services and operations over the long term without resorting to deficit financing or default. Transparency ensures that internal and external stakeholders are provided with timely information. Public officials need such information to make decisions and provide oversight, while residents and other stakeholders need accurate data on government services, performance outcomes, and fiscal soundness to hold officials accountable.

- National Archives, Code of Federal Regulations, title 31, part 35 (2022), section 35.3, link.

- Aravind Boddupalli et al., Lessons from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act for an Inclusive Recovery from the Pandemic, Urban Institute, Nov. 19, 2021, link.

- Federal Reserve Economic Data, St. Louis Federal Reserve, All Employees, State Government, February 2022, link.

- Ted Dabrowski and John Klingner, The History of Illinois’ Fiscal Crisis, Illinois Policy, link.

- Elizabeth McNichol, Out of Balance: Cuts in Services Have Been States’ Primary Response to Budget Gaps, Harming the Nation’s Economy, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 18, 2012, 6, link.

- Ed Lazere, How States Can Best Use Federal Fiscal Recovery Funds: Lessons from State Choices So Far, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Nov. 29, 2021, and updated March 11, 2022, 18–19, link.

- Major federal legislation passed in 2020 and 2021 for COVID-19 fiscal assistance includes (1) The Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act, $7.8 billion; (2) The Families First Coronavirus Response Act, $15.4 billion; (3) The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, $2.1 trillion; (4) Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act, $483 billion; (5) The Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act, $900 billion; and (6) The American Rescue Plan Act, $1.9 trillion. See Pandemic Response Accountability Committee, “Pandemic Oversight: Making Sense of COVID-19 Relief Programs and Spending,” accessed Feb. 24, 2022, link.

- The Federal Reserve action primarily included the purchase of additional long-term Treasury and mortgage-backed securities as a form of quantitative easing to support the economy. See Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, COVID Money Tracker, link.

- Consistent with the methodology used in Truth and Integrity in State Budgeting reports, we do not evaluate District of Columbia funding in this paper. States also received federal funds for nonentitlement municipalities that must be passed on to those communities without additional restrictions. Entitlement local governments received funds directly from the federal government. See American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, H.R. 1319, 135 Stat. 228, link.

- American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, H.R. 1319, 135 Stat. 228, https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/1319/text.

- US Department of the Treasury, Coronavirus State Fiscal Recovery Fund Split Payments to State Governments, Dec. 16, 2021, 1, link.

- The US Department of the Treasury released an interim final rule on the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Fund (SLFRF) program in the Federal Register in May 2021, followed by a report with frequently asked questions and answers, which was updated periodically. The Treasury released the final rule in January 2022. See Department of the Treasury, Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, 4338–39. link.

- Pay as you go refers to the financing of capital projects through sources other than debt, including taxes and fees.

- National Archives, Code of Federal Regulations, title 31, part 35, section 35.6.

- bid.

- Caitlin Devitt, “Treasury’s Legal Battle with States over ARPA Funding Heats Up,” The Bond Buyer, Dec. 6, 2021, link.

- National Association of State Budget Officers, The Fiscal Survey of States, Fall 2021, vii, link.

- American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, H.R. 1319, Sec. 604, 2001, 2003, 3201, 3206, link.

- US Department of the Treasury, Interim Reports and Recovery Plan Performance Reports—2021, link.

- The US Department of the Treasury also requested that states submit a form showing expenditures of SLFRF as of July 31, 2021. Thirty-two states entered figures into this form. A total of $8.5 billion had been spent, with negative economic impacts representing the largest amount ($3.7 billion), followed by revenue replacement ($1.2 billion). The largest subcategories of negative economic impacts were payment of unemployment benefits or cash to unemployed workers ($702 million) and contributions to unemployment insurance trust funds ($2.2 billion). Five states had made contributions to their trust fund (Arizona, $759 million; Iowa, $237 million; Kansas, $250 million; Kentucky, $506 million; and Louisiana, $490 million). Most revenue replacement spending was attributable to Nevada ($1.086 billion).

- The Volcker Alliance, Truth and Integrity in State Budgeting: Preparing for the Storm, 2021, 14–17, link.

- As of December 2020, twenty-one jurisdictions had borrowed from the federal unemployment trust fund. See Congressional Research Service, The Unemployment Trust Fund (UTF): State Insolvency and Federal Loans to States, RS22954, updated Dec. 1, 2020, 9, link.

- Jared Walczak and Savanna Funkhouser, States Have $95 Billion to Restore Their Unemployment Trust Funds—Why Aren’t They Using It?, Tax Foundation, Sept. 22, 2021, link.

- Ibid.

- Ed Lazere, How States Can Best Use Federal Fiscal Recovery Funds: Lessons from State Choices So Far, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Nov. 29, 2021, and updated March 11, 2022, 13, link.

- Jared Walczak and Savanna Funkhouser, States Have $95 Billion to Restore Their Unemployment Trust Funds—Why Aren’t They Using It?, Tax Foundation, Sept. 22, 2021, link.

- State of Indiana, Recovery Plan: State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, 2021 Report, 5, link.

- State of Connecticut, Recovery Plan: State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, 2021 Report, Aug. 31, 2021, 7, link.

- State of Minnesota, Recovery Plan: State and Local Fiscal Recovery, 2021 Report, Aug. 27, 2021, 5, link.

- Office of the New York State Comptroller, Enacted Budget Financial Plan Report: State Fiscal Year 2021–22, June 2021, 17, link.

- National Association of State Budget Officers, 2021 State Expenditure Report: Fiscal Years 2019–2021, 8, link.

- The California report shows $332 million as unallocated. See California Department of Finance, California Recovery Plan Performance Report, 2021, 18, link.

- A fiscal outlook for California released in November 2021 reported that revenues are growing at historic rates and estimated that the state will have capacity for new, ongoing commitments over a multiyear period extending through 2025–26. However, the report notes that the state could experience budget shortfalls if a recession occurs. See Legislative Analyst’s Office, The 2022–23 Budget: California’s Fiscal Outlook, November 2021, 1, 11, link.

- A Legislative Analyst’s Office report states that for fiscal 2022, California’s general fund budgeted expenditures ($196.4 billion) exceeded estimated general fund revenues ($175.3 billion) by $21.1 billion. When the budget was passed, the state planned to use the prior-year fund balance of $28.2 billion to bridge the gap and end fiscal 2022 with an estimated $7.1 billion fund balance. See California Legislative Analyst’s Office, The 2021–22 Budget: Overview of Spending Plan, August 2021, 1, link.

- Ibid.

- State Sen. Jane Nelson, “Texas Legislature Approves SB 8, Appropriating Federal Funds,” news release, Oct. 19, 2021, link.

- State of Texas, Recovery Plan: State and Local Fiscal Recovery Plan, 2021 Report, 2, link.

- Texas Workforce Commission, Annual Financial Report for the Year Ended August 31, 2021, 3, link.

- Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Recovery Plan: State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, 2021 Report, Aug. 31, 2021, link.

- State of Illinois, Recovery Plan: State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, Initial Report, Aug. 31, 2021, link.

- Illinois.gov, “Gov. Pritzker Signs FY22 State Budget into Law,” press release, June 17, 2021, link.

- State of Illinois, Budget Summary FY 2022, July 29, 2021, 28, link.

- Illinois initially considered using SLFRF to repay its Federal Reserve loan, but given SLFRF restrictions, the state decided to use tax revenues to repay the loan. See Yvette Shields, “Illinois Looks to Its Own Coffers to Pay Off MLF Loan,” The Bond Buyer website, May 21, 2021, link.

- State of Florida, Recovery Plan: State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, 2021 Report, for the period ended July 31, 2021, link.

- State of New Jersey, 2021 Recovery Plan Performance Report, Aug. 31, 2021, link.

- Gene Myers, “NJ Pumps $125M into Special-Ed Programs to Help Schools that ‘Do the Right Thing,’” July 17, 2021, Morristown Daily Record, link.

- State of Ohio, 2021 Recovery Plan Performance Report, 2021, 4, link.

- State of Georgia, 2021 Recovery Plan Performance Report, 2021, link.

- State of Michigan, 2021 Recovery Plan Performance Report, June 17, 2021, link.

- State of New York, Division of the Budget, FY 2022 Enacted Budget Financial Plan, May 2021, 11, link.

- State of New York, NYS Initial Plan for American Rescue Plan State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, Aug. 31, 2021, link.

- Although the amount was not part of the SLFRF allocation for New York State, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), which the state owns, received $10.85 billion under ARPA and the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act. This was on top of $2.9 billion in federal loans to the MTA under the CARES Act. The bulk of this money will be used for operations, which is likely to present challenges for the state after the federal aid expires. See “Governors Hochul, Murphy, and Lamont Announce Agreement on Federal Funding Awarded to the Region’s Public Transportation,” press release, Nov. 9, 2021, link.

- State of North Carolina, Recovery Plan: State and Local Recovery Funds, 2021 Report, link.

- Theresa Opeka, “General Assembly Releases N.C. Budget Plan, Including Input from Cooper,” Carolina Journal, Nov. 15, 2021, link.

- US Treasury, Title XII Advance Activities Schedule, as of Dec. 31, 2021, TreasuryDirect, link.

- Illinois.gov, “Governor Pritzker Signs Landmark Legislation Paying Off $4.1 Billion in Debt,” press release, March 25, 2022, link.

- National Conference of State Legislatures, “Fiscal 2021 State Budget Status,” March 30, 2021, link.

- State of Florida, Recovery Plan: State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, 2021 Report, for the period ended July 31, 2021, link.

- State of Michigan S.B. 82: Pub. Act 87 of 2021, Oct. 15, 2021, 4, link.

- State of Florida, General Revenue Fund Financial Outlook Statement, August 2021, 1, link.

- State of New York, Division of the Budget, FY 2022 Enacted Budget Financial Plan, May 2021, 11, link.

- The financial plan also does not explain how the annual SLFRF allocation disclosed in the plan relates to the timing of the release of SLFRF as authorized in New York S. 2509C. The latter authorizes the transfer of $6.0 billion in SLFRF in fiscal 2022 and an additional $6.5 billion no sooner than April 1, 2022, from a special revenue fund to the general fund to cover “eligible costs incurred by the State.” See New York S. 2509C, 2021, 151, link.

- Governor Gavin Newsom, California State Budget 2021–22, 2021, 36, link.

- State of Michigan, Bill Analysis: Pub. Act 87 of 2021: FY 2021–22 General Omnibus Appropriation Bill FY 2020–21 and FY 2021–22, Oct. 15, 2021, 4, link.

- State of Georgia, H.B. 81 FY 2022 Appropriations Bill, March 2021, 94, link.

- State of New Jersey, Appropriations Handbook: Fiscal Year 2021–2022, 2021, D-16, link.

- US Department of the Treasury, Compliance and Reporting Guidance: State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, accessed Nov. 21, 2021, 12, link.

- National Association of State Budget Officers, State Recovery Plans, 2021, link.

- US Department of the Treasury, Interim Reports and Recovery Plan Performance Reports—2021, link.

- US Department of the Treasury, Compliance and Reporting Guidance, State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, accessed Nov. 15, 2021, link.

© 2022 VOLCKER ALLIANCE INC.

Published April, 2022

The Volcker Alliance Inc. hereby grants a worldwide, royalty-free, non-sublicensable, non-exclusive license to download and distribute the Volcker Alliance paper titled The $195 Billion Challenge: Facing State Fiscal Cliffs After COVID-19 Aid Expires (the “Paper”) for non-commercial purposes only, provided that the Paper’s copyright notice and this legend are included on all copies.

This paper was published by the Volcker Alliance as part of its Truth and Integrity in Government Finance Initiative. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Volcker Alliance. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Don Besom, art director; Michele Arboit, copy editor; Stephen Kleege, editor.