What Employee Surveys Reveal About Working in Government

This blog was originally published in Governing.

Several weeks ago, we wrote a column about employee surveys in state and local government. It focused on the importance of using the results to take actions that improve the workplace. But as we looked into the best utility of these surveys, we grew curious about what they actually reveal—especially when compared to the federal government and private sector.

While there was good news to be found, some of the results were worrisome.

Research from the International Public Management Association for Human Resources (IPMA-HR), for example, shows that less than half of state and local employees are fully engaged in their jobs. This is particularly bad news because countless studies link engaged employees to higher productivity, better results and lower absenteeism.

This isn’t a problem unique to the public sector, though.

Private-sector employees suffer from similar issues but are actually more likely to quit when they’re unsatisfied. That’s partially because they’re less likely to enjoy the pension and health-care benefits that most government workers get. According to consulting firm Pricewaterhouse Coopers, 43 percent of public employees (compared to 32 percent of private) aren’t engaged yet have no intention of leaving.

So why are workers unhappy?

Many surveys reflect problems with communication. For example, in a survey in Michigan, only 46 percent of public employees agreed with the statement “My department leadership communicates openly and honestly with employees,” and only 44 percent concurred that “Sufficient effort is made to get the opinions of people who work here."

Communication with management appears to have a strong correlation with employee engagement. Among engaged employees in the public sector, 77 percent say they get the right amount of communication from their supervisor, according to IPMA-HR. For those who aren’t engaged, only 25 percent feel that way. Surveys also show that the longer someone works a job, the less likely they are to get feedback from people with more seniority.

Aside from open and honest communication, there are several other factors related to job satisfaction.

According to Tom Miller, president of the National Research Center, which also conducts employee surveys for state and local governments, employees are happiest when they feel their jobs fit their talents and that they’re making meaningful contributions. Interestingly, surveys show that state and local employees do well in those two categories. According to National Research Center data, more than 70 percent think they're well-suited for and helping people in their job, whereas less than 50 percent positively rate questions about performance evaluations, communications and professional development.

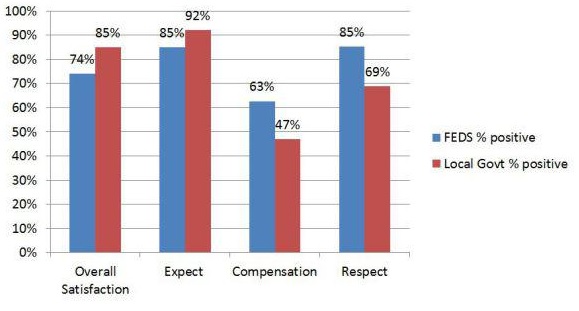

When comparing state and local government surveys to federal ones, intriguing differences emerge. The annual Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey found that local government employees were more satisfied with their jobs and more inclined to know what was expected from them. Federal employees, on the other hand, reported more positive responses to questions about compensation and respect.

(National Research Center)

When looking at individual state and local government surveys around the country, one common complaint arises: recognition (or lack thereof).

In Minneapolis, 49 percent of the city’s employees feel like they “regularly receive appropriate recognition.” In San Antonio, workers were asked to rate 38 factors on a five-point scale. Only five factors were rated below a three —two of which had to do with receiving adequate recognition. And in Washington state, recognition was one of the lowest-rated areas in its annual survey. While 86 percent of employees said they were treated with dignity and respect, only 54 percent indicated they “receive recognition for a job well done.”

The information these surveys reveal to employers can help them improve productivity and success. It’s far easier to just write off employee complaints as anecdotal or the words of malcontents. But when it becomes clear that some grievances are had by many, leaders need to pay attention.