Watch for Costly Maneuvers to Close Gaps as Budget Season Begins

This blog was orignially published by Bond Buyer.

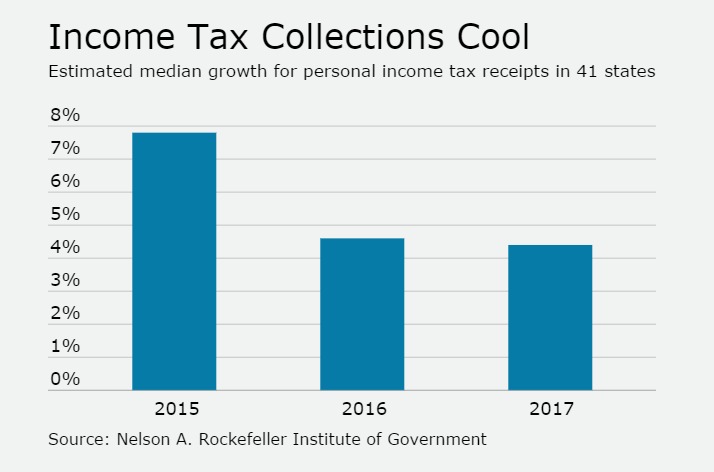

The adoptions of fiscal 2017 spending plans in Wyoming and New York this spring mark the opening of the US budget season. Legislators and governors in at least 32 more states now face a similar task. And while a few, such as New York and California, are enjoying robust growth in the nation’s 80-month recovery from the last recession, the general tone in statehouses is more one of trepidation than celebration. Across the nation, growth of state personal income tax collections will slow by almost half in the coming fiscal year, falling to a median pace of 4.4 percent from 7.8 percent in 2015, according to a forecast by the Nelson A. Rockefeller Institute of Government in Albany, New York. Sales-tax growth is also expected to cool.

Whether the cause of the slowdown is weak personal-income growth, income-tax cuts in states such as Oklahoma and Illinois, or the collapse of oil prices (Alaska, for example, derives an extraordinary 90 percent of its general fund revenue from petroleum), pressure on governors and legislators to balance their annual or biennial budgets will be intense—simply because they have almost no other option. In 49 states, balanced budgets are the law, and the lone exception, Vermont, follows its peers’ example. Yet in the tug of war between balanced-budget requirements and weakening revenue, fiscal expediency often trumps responsibility as elected officials seek to avoid general fund deficits. That was the Volcker Alliance’s preliminary finding in our 2015 report, Truth and Integrity in State Budgeting: Lessons from Three States. We’ll be looking for more of the same, as well as examples of governments that are reluctant to resort to sleight-of-hand techniques, as we expand our budget scrutiny to all 50 states in the coming year.

When examining this year’s crop of budgets, keep in mind some ways that states threaten their creditworthiness and their ability to continue delivering services by using short-term maneuvers to make it look like spending doesn’t exceed revenue. These can include borrowing long-term to fund current expenditures, shifting the timing of receipts and expenditures across fiscal years, tapping nonrecurring revenue sources to cover recurring costs, shortchanging infrastructure or legislative or constitutional mandates for education spending, or deferring funding of promised public-employee retirement benefits such as pensions and health care. Such techniques have costs that someone will eventually have to shoulder.

If you don’t think such fiscal maneuvers are perilous, look at Illinois, which for decades has spent more than its taxes and fees could support and, 10 months into the fiscal year, has yet to enact a budget for 2016. Or Puerto Rico, which borrowed repeatedly to paper over deficits and is now facing default on $72 billion in debt and the possible creation by Congress of a control board similar to those imposed upon New York City and the District of Columbia during their financial crises.

In scrutinizing budgets, it’s always a good idea to ask how a state defines revenue as well as how it is estimated. Following its near-bankruptcy in 1975, New York City was obliged to adopt budgets prepared according to generally accepted accounting principles. It remains the only major U.S. local government to use GAAP for budgeting as well as its comprehensive annual financial reports, according to a 2015 report by City Comptroller Scott Stringer.

“In applying this standard as a bulwark for New York City’s budget,” Stringer said in the report, “the State’s intention was to put an end to the City practice of funding operating expenses with capital funds and obscuring operating deficits as it was doing under cash accounting in the 1970s.” By putting an end to that, Stringer said, the nation’s most-populous city has been able to pass a truly balanced budget each year and maintain access to capital markets.

Doing so shows the saving to taxpayers that honest budgeting can yield. Consider this tale of two bonds, one from a GAAP-budget issuer and the other not.

As of April 14, a 5 percent New York City general obligation bond maturing on August 1, 2026 traded at a yield of about 1.98 percent, only 33.8 basis points over that for AAA rated tax-exempt debt of comparable maturity, according to Bloomberg BVAL data. By contrast, a 5.5 percent general obligation issued by Illinois and maturing on July 1, 2026 was yielding 3.38 percent, or 205.4 basis points over top-rated debt. (A basis point is one one-hundredth of a percentage point.) Years of budgets balanced through borrowing, fund sweeps, underfunding public-employee pensions, and other techniques are obviously exacting a market as well as human cost.

We’ll get several more chances shortly to measure the cost of borrowing to balance the books. Louisiana, hard hit by slumping oil and natural gas prices as well as by tax cuts by two former governors, Democrat Kathleen Blanco and Republican Bobby Jindal, now faces a $1.6 billion structural budget gap equivalent to 18% of spending, according to Bloomberg. To help close the gap, the state plans to sell $359.3 million of debt, which the Bond Buyer reported is the first “scoop-and-toss” deal officials can recall. One of the budget-balancing techniques the Volcker Alliance has highlighted, scoop and toss is a way to refinance previous obligations while pushing the day of reckoning on the debt years into the future.

In Kansas, where regulatory filings show the state pension has only 65% of the assets needed to pay promised benefits, officials may offset some of the impact of income-tax cuts by borrowing against its share of revenue from the 1998 national settlement between tobacco companies and states and cities. Oklahoma, meanwhile, may need to sell bonds to erase a $1.3 billion deficit. Such deals may take care of today’s gaps, but they do little to fix underlying imbalances that threaten to burden generations to come.