Ten Secret Truths About Government Incompetence

Congratulations! You’ve won the nasty 2016 election for president of these United States. It was a long slog through more bad chicken dinners and dusty halls than anyone could be expected to tolerate. You won because you listened carefully to Republican strategist Frank Luntz’s take on the 2014 midterm election, that the “results were less about the size of government than about making government efficient, effective, and accountable.” And that’s just what you built your campaign on.

On January 20, 2017, you’ll be sworn in at noon, give a great speech, sneak out of the Beast for as much of a walk down Pennsylvania Avenue as the Secret Service will allow, cheer your hometown high school band, and dance the night away.

And then you’ll take over as chief executive and actually have to do what Luntz said: make government more efficient, effective, and accountable. As you settle into your new chair in the Oval Office, here are ten handy truths worth keeping in your pocket or purse.

I. Government works better than people think. Most of the time.

You told us during the campaign that government programs fail often, and a September 2014 Washington Post/ABC News poll shows that most Americans agree. Of those surveyed, 74 percent said they were dissatisfied or angry with the way the federal government works. Another 23 percent were satisfied—but not enthusiastic. Those enthusiastic about the federal government’s performance? Just 1 percent.

In fact, however, much of government actually works pretty well, most of the time. The Heritage Foundation points to “the breathtaking, long-term improvements in safety in the airline industry,” with tough, smart work by the National Transportation Safety Board leading to just a single fatal accident on an American airline since 2009, when a commuter jet crashed near Buffalo. For all the (often overblown) concerns about the long-term fiscal strength of Social Security, the bureaucracy that actually administers the program, the Social Security Administration, makes monthly payments to sixty-four million Americans with an accuracy rate of more than 99 percent and administrative costs that are (at 0.7 percent) but a fraction of those of private pension plans. Harvard University researchers found that stronger government regulations for air quality have led to longer lives. Even at the troubled Veterans Health Administration, a new technology system shrank the claims backlog by 60 percent.

Government usually gets only the hard problems—the puzzles that the private sector cannot or will not tackle, or that the private sector itself creates. In 2009, the United States found itself the majority stockholder in General Motors and pumped billions into Chrysler. Government bailouts saved an insurance company (AIG) and a bank (Citigroup). With its $49.5 billion bailout, the feds saved GM and millions of jobs, lost just $11.2 billion in the turnaround, and got out of the car business by the end of 2013. The government actually made money—$22.7 billion—on the AIG bailout and another $15 billion on Citigroup, far offsetting its auto-industry loss. Six years after the government launched these bailouts, it’s still staggering to imagine how bad things would have gotten if the government had left private enterprise to itself. And these weren’t aberrations. Again and again over the years, Washington has bailed out companies deemed vital to the economy, like Lockheed in 1971, Chrysler in 1980, and the entire airline industry after 9/11. Each time, the actions saved the companies and Washington made a profit on its investments.

A huge part of government works pretty well most of the time, as we take for granted every time safe drinking water comes out of the tap. You start your administration with a lot of points on the board, even if not many citizens notice the score.

II. Good management doesn’t win elections—but bad management can ruin presidencies. Fast.

The painful experiences of your two predecessors create a stark warning: voters don’t reward good performance, but they fiercely punish bad management. For George W. Bush, the point at which his negatives exceeded his positives and never recovered was not “Mission Accomplished” or Abu Ghraib. Rather, it was the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in September 2005. Barack Obama tumbled down the same road after the failed launch of the Obamacare website in October 2013, at almost the same point in his presidency.

It isn’t an inevitable part of second-term-itis. Bill Clinton fought off the impeachment barrage and Ronald Reagan was besieged by Iran-Contra, but neither took the hit in presidential approval that Bush and Obama suffered. The difference? The Clinton and Reagan battles were fundamentally political. The Bush and Obama problems were at their core managerial. The managerial failures created a negative narrative into which other problems played and on which their opponents relentlessly piled. For Team Obama, there’s been Benghazi, the IRS, the Obamacare website, the VA, the Secret Service, Ebola, and a lengthening list of other managerial mishaps. The Republicans turned this into a winning play in their battle for Congress in 2014: the president didn’t know what he was doing, they said, and Democrats needed to pay.

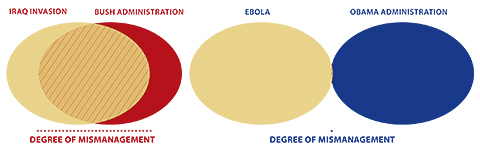

III. We don’t distinguish between failures that are truly consequential and those that have lesser impact.

You’ve benefited from the “Obama is incompetent” narrative. It increased the public’s appetite for getting you—and some fresh air—into Washington. But let’s be honest: you lucked out because of the media’s inability or unwillingness to notice, care about, or explain the difference between hugely consequential management screw-ups and only modestly consequential ones.

Failing to plan for the occupation of Iraq? Disbanding the Iraqi military? Putting inexperienced political cronies in charge of the Federal Emergency Management Agency and downsizing the agency prior to Hurricane Katrina? Now those were screw-ups—big, far-reaching, world-historic blunders that led directly to the deaths of thousands.

But Ebola? In the United States (as opposed to Africa) Ebola claimed two victims through the first few months, both travelers from West Africa who arrived at hospitals already gravely ill. In all, three health care workers, two in Dallas, one in New York, caught the disease—and then they recovered. The media’s freak-out over this story was insane. True, administration officials fed the frenzy with some inaccurate early assertions and advice—for instance, that the safety protocols the Centers for Disease Control had provided hospitals were not as careful and detailed as they needed to be. But within a few days the administration had better calibrated its media presence, the CDC had issued stronger protocols, and the outbreak had died down, just as the agency predicted. Meanwhile, in Texas alone, twenty children died in the 2012-13 flu season, and annual deaths from the flu across the nation range from 3,000 to 49,000—numbers that provoke mostly yawns from reporters.

The media mis-calibrated other big stories. In the Obamacare website fiasco, no one died. It took people a few extra months to sign up for care. Early press reports that forty veterans had died because of long wait times for primary care appointments at the Phoenix and other VA hospitals turned out to be bogus. The department’s acting inspector general told lawmakers that the embarrassingly long wait times in places like Phoenix “may have contributed” to patient deaths but that his investigations had turned up no conclusive proof that any vet had died.

Of course, these were big stories—but they were mostly big political stories. The stumbles embarrassed the Obama administration, hinted at an underlying management problem in the administration (more on that shortly), and helped the Republicans weave a powerful campaign narrative. But the stories weren’t about big failures with huge consequences. They were about putting torpedoes below the political waterline.

IV. We say we want to run government more like the private sector— but we expect government to meet standards that the private sector could never manage.

You made the case in your campaign that government needs to learn from the best-run private companies. That’s an irresistible line that Republicans invented and Democrats—especially Obama—have come to champion. But, of course, you know that the private sector isn’t always a model of good management. Remember New Coke, Windows 8, the collapse of Chi-Chi’s restaurants, and shrapnel-filled airbags? That’s even before we get to the wholesale financial miscalculations and fraud that led to global economic collapse.

The private market has a big advantage over government: it can bury its bodies in balance sheets and deal with its failures by quietly turning out the lights and locking the doors. Government’s problems, no matter how small, are fodder for news headlines (see point #3): “Report: DHS Employees Put $30,000 Worth of Starbucks on Government Credit Card.” We need to insist on government transparency, but sometimes that only creates more fodder.

For instance, how do we know that some VA facilities failed to measure up to the department’s fourteen-day maximum wait time for first-time primary care appointments? Because the VA measures such wait times and then, through its inspector general, makes its failure rates public. Private health care systems don’t disclose their wait times or have an inspector general looking out for patients and the financials. The only data we have on wait times at private-sector hospitals comes from a periodic survey by a health care consulting group. Compare those survey numbers and the VA’s numbers (the audited ones, not the “juked” stats), and it turns out that on average the wait time at the VA isn’t much different than in the private sector.

Expectations for government are higher than for the private sector and impossible to meet. Failures, no matter how small, hit the media spotlight. Government even gets blamed for private-sector failures. When investigators from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration discovered that Takata airbags killed and injured drivers, they recalled millions of cars. And who did members of Congress blame for the failure of private car companies to oversee the quality of supplies they bought from another private company in Japan? The NHTSA, of course.

V. Much of government’s work isn’t done by government.

You might think you’re the chief executive, but you don’t directly manage most of the programs for which the public holds you accountable. That’s because much of government isn’t actually done by government. The federal government spends $1 trillion per year on Medicare, Medicaid, and related programs, but private and nonprofit medical facilities actually provide the care. The Affordable Care Act is a federal mandate that requires individuals to have health insurance, and it provides subsidies for people who can’t afford it. But the government doesn’t provide the health insurance under the ACA, or the health care the insurance buys: all that comes from the private-sector actors, including some who are greedy, dishonest, and incompetent. The defense budget is a similar story. The Pentagon doesn’t build its own weapon system; private-sector defense contractors do. Amtrak doesn’t own most of the track on which its trains run. When Amtrak trains run late—and only two of its routes meet the national on-time standard of 85.5 percent—it’s most often because privately owned railroads have failed to maintain the tracks or have given priority to their own freight trains. Most of what the federal government does is outsourced to the private sector or to state and local governments. Only about one-sixth of the budget goes to work performed by government employees.

Of course, this doesn’t mean citizens won’t hold you accountable for fraud, waste, abuse, and mismanagement. You just don’t have direct management control over many of these problems. Much of your job isn’t what people think it is, or what you imagined it would be when you ran for office.

VI. The problem isn’t too many bureaucrats—it’s too few.

Out of frustration, critics—including pundits, many members of Congress, and a fair number of presidential candidates (maybe even you), play an “Off with their heads” strategy: Fire some bureaucrats, and then fire some more until they get the message. Fire more still, to starve the government’s ability to intrude into citizens’ lives. It makes for good press, but it’s a dangerous game, for several reasons.

First, while Washington is the nerve center of the federal government, 88 percent of all feds work outside the D.C. metropolitan area, and most of them do things around the country that citizens want or that government can’t do without. There are Social Security claims workers who help people get their monthly checks, air traffic controllers and Transportation Security Administration screeners who keep air travel running, rangers who tend to national parks, and FBI field agents who track down the most wanted. If you cut across the board, you’d have to eliminate seven feds around the country for each D.C.-based bureaucrat who’d lose a job. The government shutdowns have shown that people quickly notice the difference.

Second, because government workers don’t do much of government’s work (see point #5), cutting feds reduces government’s leverage over the vast and interconnected network of private programs and contracting firms that actually work the front lines. If you want to cut defense waste, you have to figure out how Pentagon staffers can do a better job overseeing contracts. Estimates of waste and improper payments in the Medicare program range as high as $120 billion a year, but you can’t reduce that without getting a handle on people outside government who don’t work for you—and to them, that $120 billion isn’t waste, it’s a windfall they’ll fight to keep.

Here’s a cautionary tale. In the 1990s, thanks to the Clinton administration’s military downsizing and mandates by the GOP Congress, the number of contracting officers at the Department of Defense fell by 50 percent—from 460,000 to 230,000. Many of those civil servants didn’t have the skills to oversee increasingly complex weapon systems and service contracts, and they needed to be replaced. But better-skilled replacements were not hired. Then came 9/11 and the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Suddenly, defense spending soared by hundreds of billions of dollars. Much of that money went to contractors, but it was overseen by what a later Army report called “a skeleton contracting force” of civilian bureaucrats. One result was a horrific chain of accidents—at least twelve in all—in which soldiers serving in Iraq were electrocuted while taking showers. Congressional investigators pointed to the failure of a contractor hired by the Pentagon to perform maintenance on the facilities. Private-sector contractors committed many of the atrocities at the Abu Ghraib prison, to the point that Iraqi prisoners won a $5.8 million judgment against one company. The depleted ranks of civil service acquisitions specialists also contributed to a huge spike in weapon cost overruns, from 6 percent for the average weapon system in 2000 to 25 percent in 2009. Cost overruns for that year alone totaled $296 billion.

Since then, the Obama administration has beefed up the Pentagon contracting force and brought more work in-house, and that’s helped. But Obama, too, has felt the political pain of relying on undermanned bureaucracies to carry out his signature policies.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) manage about $1 trillion in federal spending—the two health programs plus the state Children’s Health Insurance Program—with just 5,720 employees. That’s 0.2 percent of all federal employees responsible for 28 percent of all federal spending; each employee is responsible, on average, for an astounding $175 million in government spending. Every employee who is cut puts more money at risk, unless government can figure out a smarter way of overseeing the programs. And that hasn’t happened—the CMS’s programs were charter members of the Government Accountability Office’s (GAO) “high-risk list” of the programs most prone to waste, fraud, and abuse and have been there for twenty-four years.

Meanwhile, as the CMS was overwhelmed with managing two of the government’s biggest programs, it got the job of setting up the federal Obamacare website and creating the federal insurance marketplace. But it didn’t have the staff or the expertise to do the job—the CMS, after all, is a payment-management agency, not a website-design operation. The GAO found that the agency launched the procurement without figuring out what it wanted to buy, which led to a system that didn’t work at first and suffered from enormous cost overruns. Bad things happen when agencies are responsible for important work they don’t have the capacity to do.

This only scratches the surface of the chilling stories that spill out of the GAO’s reports, especially its high-risk list. The biennial report is gripping reading only for the most wonky of policy wonks, but the underlying story is scary and clear. There are thirty programs on the list, and twenty-nine of them have roots in human

capital—getting the right people with the right skills in the right place to solve these problems. The thirtieth program? Human capital itself.

In an August column in the Washington Post, the political scientist John DiIulio asked, “Want better, smaller government?” His answer: “Hire another million federal bureaucrats.” We have no hope of making government work, he wrote, if we don’t hire the government we need to run it—and to rein in the proxies who do so much of the government’s work on its behalf. Much of the talk you hear about how government should be run more like the private sector is nonsense—there are too many fundamental differences in mission, expectations, and accountability. But one piece of advice from successful CEOs you should heed is that the people who work for you are your most important asset. Make sure you have enough of them, in the right places, with the right skills. If you run them down, you undermine yourself.

VII. Half the time, when it looks like it’s the president’s fault, the problems really come from Congress.

Citizens, reporters, and members of Congress deeply believe that the president is responsible for problems when they pop up. But in a huge number of cases, problems in executing laws start in the way Congress writes them.

Let’s go back to the VA for a moment. The ultimate reason why front-line employees at some VA centers couldn’t meet the department’s fourteen-day maximum wait time standard (and chose instead to falsely report their results) was that there was a shortage of primary care doctors to meet the demand from newly enrolled veterans. But the shortage of primary care docs is a nationwide challenge, and Congress contributes mightily to the problem. Every year Congress dishes out $13 billion to academic medical centers for physician training, most of which goes to producing more cardiologists, radiologists, and other specialists that fatten the hospitals’ bottom lines. Congress could demand that more of those dollars go to training primary care docs. It could also increase Medicare reimbursement rates for primary care relative to specialty care. These two reforms would go a long way toward relieving the primary care doc shortage. But because of pressure from the specialist physician lobbies, Congress chooses not to.

Or consider the beleaguered U.S. Postal Service. Congress demands that the service cover all its own costs, like a for-profit business, with no help from the Treasury. Yet it still insists on micromanaging the agency. To cover its growing revenue shortfalls, USPS leaders and outside experts have proposed a long list of ideas: End Saturday delivery. Close underutilized processing facilities. Spend less on pre-funding the employee retirement system. Open revenue-producing “postal banking” services for customers. Congress has refused to approve any of these ideas.

Congested highways making your commute longer? Maybe that’s because Congress can’t even pass a transportation bill, let alone legislation that adequately funds transportation infrastructure, including mass-transit systems. Got food poisoning? Maybe that’s because Congress has all but defunded meat inspection. Worried about where the next big storm is heading? Congress has undercut the National Weather Service’s ability to collect and distribute data. Pick almost any government performance problem and at least some (often most) of it can be traced back to some congressional action or inaction: conflicting statutory mandates, poor oversight, a failure to grant agencies sufficient authority to get the job done, ridiculous loopholes for favored private interests, grossly inadequate funding, and other problems.

It’s certainly not the case that Congress doesn’t care about government. Sometimes it smothers bureaucracy with love: a mind-boggling collection of 108 committees and subcommittees have oversight over the Department of Homeland Security. In fact, homeland security oversight is getting even more popular. The homeland security committee menagerie was just eighty-six in 2004, when the 9/11 Commission warned about the fragmentation of congressional oversight. It’s ballooned since then into one of the Capitol’s biggest time sinks. The Hill reports that in 2012 and 2013, 391 officials from the department testified before Congress in 257 hearings, in addition to 4,000 briefings. The department’s remote location on Nebraska Avenue, six miles from the Capitol, guarantees that department officials will spend a huge amount of their time stuck in traffic to satisfy the insatiable congressional appetite for a piece of the homeland security action. But there’s no evidence that this oversight is helping: the department is one of the government’s most troubled, and its management has been on the GAO’s high-risk list.

VIII. Critics of your government will create self-fulfilling prophecies by underfunding and otherwise sabotaging programs they don’t like.

An especially cynical strategy has emerged in recent years. Antigovernment forces have consciously tried to sabotage government—by shutting it down, slashing the budget, and attacking bureaucrats—with the clear goal of undermining the president’s ability to manage. If opponents can’t eliminate the programs they oppose, they can starve and cripple them. Failures then inevitably crop up. The news cycle doesn’t differentiate between problems that are consequential and those that aren’t (see point #3). What matters is creating a drumbeat of a gang that can’t shoot straight, and finding new stories to reload the ammo as the old tales fade away. Doing the public’s business gets lost in the battle of driving the other guy out of town. The Constitution anticipated one way to deal with the core questions about government, of course: if you don’t like a law, change or repeal it. In gridlocked Washington, however, it’s too hard to do that (or much of anything else). It’s much easier to sabotage government’s long-term operations for short-term political purposes.

This strategy is made possible by a quirk in public opinion: most Americans don’t like government, but they sure do like government programs. When sequestration loomed in early 2013, the Pew Research Center for the People and the Press surveyed citizens about what programs ought to be cut. The result: of the nineteen programs on the Pew list, none commanded a 50 percent vote for cutting.

Cutting government waste, of course, really means cutting the other guy’s programs. Deep in the heart of Texas Tea Party country in 2011, there were constant cries to slash government spending. But when wildfires swept through the central part of the state, GOP Representative Michael McCaul, who represents a district stretching from Austin to Houston, complained that the U.S. Forest Service didn’t have tankers at the ready. “Despite all the warnings that Texas faced with it being the driest summer in more than 100 years, there was no prepositioned aircraft to help,” he said. Local residents savaged the USFS for canceling a contract with Aero Union, a California company whose ancient planes, some of which were fifty years old, didn’t meet basic safety standards. They complained more when the agency went looking for help and brought in air tankers from outside the country. But the USFS is responsible only for fires in national forests, and only a tiny fraction of the Texas fires were on federal land. So the agency caught flak from antigovernment activists who complained that they weren’t getting government help fast enough—and that the feds weren’t there to do the state and local governments’ work. By the way, Representative McCaul was reelected in 2014, winning 62 percent of the vote.

IX. Government can be made much better relatively quickly—and can be made worse even more quickly.

After the disastrous launch in 2013 of the ACA website, many Washington pundits asked whether Americans would ever trust the government again. But an equally important story, one almost no one knows, is how quickly a skilled team of feds and private contractors turned the website around. Obama put a former top Office of Management and Budget official, Jeff Zients, in charge. He hired a systems integrator to ride herd on the project and launched a “tech surge” to fix the site and its back-office operations. By December 2013, in three months of nonstop work, the team stabilized the site and ended the “Please try again” messages that bedeviled it at its launch. In November 2014, when the health marketplaces went live around the country, the headlines said “Insurance Exchanges Launch with Few Glitches,” with up to nine million people expected to sign up by the end of open enrollment on February 15, 2015.

There’s an important lesson here for you: government screw-ups can happen quickly, but with the right leadership and energy they can be resolved quickly, too. That is true not just of individual initiatives, like the exchanges, but of whole agencies.

No federal agency demonstrates more clearly how fast big problems can be solved—or how quickly progress can evaporate—than FEMA. The agency created its own disaster when it fumbled the response to Hurricane Andrew’s devastating blow to Florida in August 1992. Pundits afterward wondered if the management failures nearly cost George H. W. Bush the state’s electoral votes. When he became president, Bill Clinton appointed a skilled administrator, James Lee Witt, to engineer a FEMA turnaround. By 1995, Daniel Franklin wrote in the Washington Monthly that “FEMA transformed itself from what many considered to be the worst federal agency (no small distinction) to among the best.” Instead of showing up to write checks after disasters, FEMA worked with communities before disasters happened to reduce risk and damage. The agency discovered, for example, that it was much cheaper to retrofit homes in advance of storms to keep the roofs from blowing off than to pay afterward to put the roofs back on—and to repair or replace flooded homes—so it built partnerships with Florida local governments to make that happen.

FEMA’s success didn’t last long, however. The mega-consolidation that brought twenty-two agencies, including FEMA, into the new Department of Homeland Security derailed the improvements of the Clinton years. After Hurricane Katrina nearly drowned New Orleans, President George W. Bush put his arm around FEMA administrator Michael Brown and famously said, “Brownie, you’re doing a heck of a job,” at precisely the time it was clear that neither he nor FEMA were. David Paulson soon replaced Brown and began getting the agency back on track. Obama’s appointee, Craig Fugate, continued the progress so that, when Superstorm Sandy attacked the northeastern coast, the headline that didn’t appear was “FEMA Fails Again.” The agency’s partnerships with state and local governments, as well as with the private sector, proved a model of disaster response. Companies like Home Depot and Walmart became integral parts of FEMA’s “whole community” strategy, focused on “creating active public-private partnerships to build disaster-resistant communities.” That made a huge difference when the storm hit.

The bad news is that the loss of top-level attention can quickly drive well-functioning agencies to disaster. The good news is that strong top-level leadership can turn poorly performing agencies around. FEMA has gone through the down-and-up cycle twice in the last twenty years. If you pay attention to the game—see point #10—you can avoid this roller-coaster ride.

X. Presidents can win the game if they pay attention.

You won’t be able to avoid the nine truths we’ve explored so far, and they’re full of traps that can undermine your presidency when you least expect it. But you have more ways to avoid those traps than you might imagine.

There are five important, straightforward steps. First are the 3,000 appointments that you directly make in the executive branch. You need a White House personnel operation that goes beyond satisfying campaign contributors to making sure you get the right people in the right jobs with the right skills and instincts.

The second is the civil service. You badly need the best and the brightest to support the executive branch’s work. If you don’t get good performance, you’ll pay—dearly. And the huge impending turnover in the federal workforce is a bigger challenge than you think. Almost a third of the federal workforce will be eligible to retire as you take office. Half of all air traffic controllers could move out as you’re moving in. In the Department of Housing and Urban Development, that number is 42 percent, and it’s 44 percent in the Small Business Administration. You might look to millennials, who want to find jobs where they can have an impact. But right now, many of them are drawn to the nonprofit sector, because the government hiring process is a mess and they worry that if they join the government they’ll be caught up in too much red tape and too little entrepreneurship. More generally, the feds are getting fed up with being the punching bag for dysfunction elsewhere in government. You need to worry about this—and to recruit a leader for the Office of Personnel Management who can get the federal government’s strategy right.

The third step is making sure that the President’s Management Council runs well. This is the group of the departments’ deputy secretaries, chaired by the OMB’s deputy director for management. The PMC has had its ups and downs—but when it has been run well, it has provided a direct connection between the White House and the people who actually manage the agencies. The PMC members can be the best friends you didn’t know you needed.

A fourth step is tougher. You need a chief operating officer, someone who can look after the details when you are busy with everything else and speak for you when management muscle is needed. You’ve got three options here.

Option 1: Make your vice president the chief operating officer. Al Gore got Clinton’s blessing to run the National Performance Review from the vice president’s office. Dick Cheney had a huge scope of operating responsibilities in the Bush years. Joe Biden launched and oversaw the $831 billion Recovery Act with nary a scary headline about fraud. These VPs-as-COOs provided valuable service to their presidents, but it’s a potentially risky strategy, since it can create a rival political camp. Moreover, the history has been uneven—Gore barely mentioned the NPR in his presidential campaign, Cheney’s power unsettled many Washington hands, and Biden’s role ebbed after the Recovery Act’s successes. But the vice presidency can be a lot more than a “bucket of warm spit,” as one of Franklin Roosevelt’s vice presidents, John Nance Garner, put it.

Option 2: Run government management through the “M” in OMB. The Office of Management and Budget has a deputy director for management, charged with overseeing the federal government’s operations. You could strengthen this post and give the deputy director muscle (it needs at minimum a doubling of its staff). But this has been a troubled position for a very long time. The “B” (budget) side of OMB has always been more powerful than the much smaller “M” (management) side, and both wings have struggled with staffing reductions in recent years. You need help. This could be the place to get it.

Option 3: Create a czar of czars in the White House. A new post of deputy chief of staff of operations would pull management more clearly into the presidential orbit and give the president’s voice to management issues when the czar of czars speaks (quietly and behind the scenes, of course). It would be an ugly job, pushed aside by the inner-circle power brokers (jealous of their time with you), charged with doing things that most people around you won’t think are important (until it’s too late), ignored by bureaucrats (unless you make it clear that they need to listen), and staffed by someone who will always struggle to stay a step ahead of what’s going on out there (because the more powerful your deputy becomes, the less administrators will want to tell him or her). But the post could also help your administration become less insular. That was a growing problem for both Bush and Obama, the deeper they got into their terms.

The fifth step is dealing with Congress on the management of government. The political rule in Washington is that whatever goes wrong in the bureaucracy is the president’s fault, even if so many problems flow from Capitol Hill. For your sake and the country’s, this misperception needs to be shattered, and you can strike a blow for sanity right away. At your first State of the Union address, announce that you will submit a sweeping plan to fix the big problems in law that cripple the federal government’s management and performance. Tell the assembled lawmakers that if they fail to act on these proposals and screw-ups arise, you know you will be held responsible, and that’s part of your job. But this time, tell them, Congress will share the blame. The point here is not to duck responsibility but to create joint accountability. Fixing a federal bureaucracy as big and complex as ours is not something any president can do alone. You need Congress’s help, and Congress needs political incentives to care. Create those incentives, and great things could happen.

You have more options than you think. You ignore them at your peril. And if you’re like most presidents, you won’t discover that peril until you’re up to your knees in it trying to figure out how it happened. You can learn these ten truths the easy way now, or suffer from them the hard way later. But you can’t escape them.