States Finding Infrastructure Fixes as Congress Drags Feet

While Congress dithers over a long-term transportation funding bill, U.S. states increasingly are taking things into their own hands, raising taxes on motor fuels and considering other measures to help rebuild inadequate or crumbling highways, bridges, water facilities and other infrastructure that are key to their economic growth.

Taken together, the measures may finally begin whittling away at the $3.6 trillion that the American Society of Civil Engineers estimates is needed for infrastructure investment by 2020. Among governments in need, California suffers from a $64.6 billion shortfall in deferred maintenance, the Volcker Alliance’s Truth and Integrity in State Budgeting report concluded earlier this year, citing the state’s Five-Year Infrastructure Plan. And New York City alone requires more than $47 billion of infrastructure investment, according to the Center for an Urban Future.

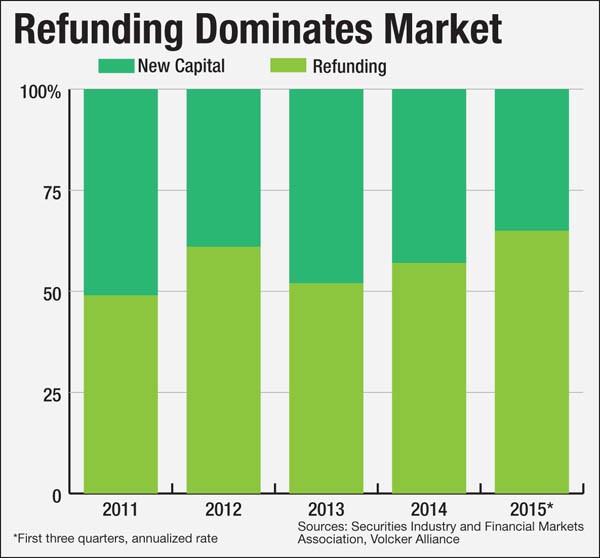

The $3.7 trillion municipal bond market, which exists largely to finance capital projects, may benefit along with commuters from the infrastructure moves if states, agencies, and localities choose to borrow against the new revenue to provide immediate infusions of construction cash. Last year, 57 percent of muni issuance went to refinance old debt rather than finance new projects (table), and refundings are on pace to capture as much as 65 percent of the market in 2015, as bond yields remained near generational lows, based on Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association data for the first three quarters.

A decade ago, 54 percent of munis were new debt. But with today’s needs so great, “everybody is talking about infrastructure,” Raul Amezcua, managing director at Stifel Financial Corp., told the Bond Buyer’s California Public Finance Conference in October.

In some states, talk is turning into action. Sixteen states—including several governed by frequently tax-averse Republicans—have raised gasoline or diesel-fuel levies since 2013, according to Carl Davis, research director at the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. Voters in Texas, another solidly red state, meanwhile, will consider dedicating billions of dollars to highways via Proposition 7 on the Nov. 3 ballot.

Starting in 2017, the ballot measure, Proposition 7, would funnel at least $3 billion a year into road building and maintenance from the state general fund and taxes on motor-vehicle sales and rentals, according to a Dallas Morning News estimate. It comes on top of voter approval in 2014 of a constitutional amendment to shift some energy production tax revenue from the general fund to highways, which threaten to become choked as Texas’s population swells to a projected 45 million in 2035 from 27 million today. The measures will also help fill the gap caused by a decline in the purchasing power of the state’s 20-cents-per-gallon gasoline tax since 1991, which the newspaper reckons is worth only 9.2 cents in real terms today.

Not every state is moving in lockstep to boost or tap tax revenue for infrastructure. In Louisiana, even as voters on Oct. 24 approved a constitutional amendment allowing the state treasurer to help provide low-cost financing for local projects by investing in the state infrastructure bank, they also turned down another amendment that would have established a transportation fund fed by oil and gas revenue. And while a recent Rutgers-Eagleton poll shows that 54 percent of New Jersey residents think the Garden State fails to spend enough on roads and bridges, only 37 percent favor increasing the state’s 14.5 cents-a-gallon gasoline tax—America’s second-lowest—for the first time since 1988. Republican Governor Chris Christie and the Democrat-run legislature have been unable to agree on a new transportation-funding plan, and without more tax revenue or another new source of cash, the state’s Transportation Trust Fund may run out of money for anything but debt service by the end of June.

Increasingly, though, New Jersey may be an outlier. While U.S. House lawmakers have proposed a six-year transportation bill, they haven’t been able to come up with a way to fund the entire measure or align their plan with a separate version passed in the Senate. So while the wait goes on, states will have to rely on their own wits—and resources—to get their roads, bridges, and buildings into proper shape.