Muni Debt in the US and China: Notes from an ASPA Discussion

Municipal debt—and what governs issuance, yields, and the consequences of too much borrowing—was the focus of three academic papers on the US and China delivered during a fascinating panel that I chaired at the recent annual meeting of the American Society for Public Administration in Seattle. The conclusions that emerged are that politics cannot be removed from issuance and that perverse incentives sometimes drive local officials to build mountains of debt that may be difficult to repay without help from national authorities. Here are highlights of the panel session—you will also find the academics’ PowerPoint presentations below.

China’s $2.5 Trillion Local-Debt Bubble

While Puerto Rico’s likely inability to repay $72 billion in commonwealth, authority, and local bonds is currently driving the US Congress to consider a bill allowing for a possible debt restructuring and the establishment of a fiscal control board, China is also grappling with as much as 16 trillion renminbi ($2.5 trillion) in borrowings by local governments. The debt is for building infrastructure and housing as well as to close budget deficits, according to a paper by Mengzhong Zhang, of the John W. McCormack Graduate School of Policy and Global Studies of the University of Massachusetts-Boston, and Youwei Qi, of the School of Public Affairs and Administration at Rutgers University-Newark. Noting that Chinese local debt swelled almost 10-fold from 2004 to 2014, Zhang and Qi estimate the total burden may increase further, to 23 trillion renminbi.

“If the Chinese government does not curtail this dangerous trend of taking on debt for various purposes over the next few years,” Zhang and Qi warn, “the situation may spiral out of control,” not only threatening banks that have lent to localities but also threatening social stability and the national economy. While they call for the creation of an organization in the central government to manage local debts, it is unclear whether that would remove the incentive that local leaders—who are appointed by Communist Party officials—have to borrow even more. They sum it up thusly:

Local government officials have `found’ that borrowing money to drive economic development is a very effective way to stimulate GDP growth, while individual officials do not need to be responsible for the sudden large increase of the government debts.

The Chinese local government leaders’ performances have mainly been measured by the economy development (GDP) and their promotions depend on the GDP of local governments to a large extent. Society wants officials to take the long view, but individual government bureaucrats just want successes to last long enough for them to be promoted elsewhere.

Until incentives such as these are reformed or eliminated, it’s hard to fathom how even a government bailout of local debt would prevent the bubble from forming again.

How Politics Drive State Bond Sales

The political makeup of states helps determine how much long-term debt they are willing to issue in the $3.7 trillion US municipal bond market, according to Koomin Kim and Seunghoo Lim, of the Reubin O’D. Askew School of Public Administration and Policy at Florida State University. In their paper, the researchers present a guide to the most significant political indicators that investors may want to track as well as other indicators such as limits on budget deficits and borrowing.

When they looked at which party controls legislative houses and the governor’s office, Kim and Lim found that states with both branches dominated by Democrats tend to be “more responsive to citizen demands” and more willing to borrow, while competition among parties for control of the branches reduces a state’s overall long-term debt. Not surprisingly, constitutional limits on long-term debt also lead to reduced borrowing, they found, as do balanced budget rules.

This last point may need further study. While 49 states require balanced budgets (and the lone exception, Vermont, follows the example set by its peers), the definition of revenues, much less “balanced budget,” varies from place to place and is often subject to the kind of one-time fiscal maneuvers that the Volcker Alliance chronicled last year in Truth and Integrity in State Budgeting: Lessons from Three States. When politicians are able to borrow, sell assets, or drain special accounts to cover general fund budget gaps, the books may be balanced in name only. The existence of a balanced budget rule may thus be a false signal about a state’s willingness to sell long-term debt.

Does State Oversight Increase School District Borrowing Costs?

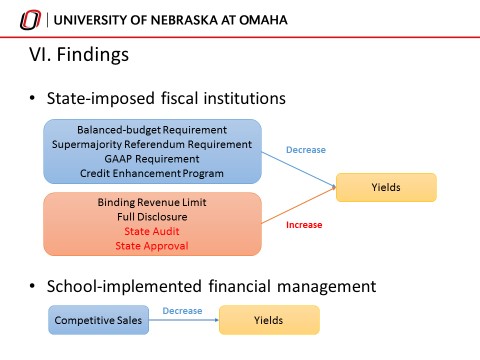

Because school districts are among the biggest issuers of long-term US municipal debt, scoping out the forces that influence their bond yields should be of paramount importance to issuers and investors alike. Junghack Kim, of the University of Nebraska at Omaha, reviewed 9,812 bonds issued in 2014 by independent school districts in 18 states. Among their findings:

While the research would benefit from clearer descriptions of “balanced budget” and borrowing costs (are they absolute or relative to US Treasury or AAA rated municipal bonds, for example), the paper did highlight some surprising findings. Among them, Kim says, are that requirements for state approval of bond issues and audits of school districts’ finances appear to increase borrowing costs. A possible explanation is that these rules may have stemmed from states’ casting doubt on school districts’ financial management. “This might not bring a positive image” to bond market participants, he says.

While the research would benefit from clearer descriptions of “balanced budget” and borrowing costs (are they absolute or relative to US Treasury or AAA rated municipal bonds, for example), the paper did highlight some surprising findings. Among them, Kim says, are that requirements for state approval of bond issues and audits of school districts’ finances appear to increase borrowing costs. A possible explanation is that these rules may have stemmed from states’ casting doubt on school districts’ financial management. “This might not bring a positive image” to bond market participants, he says.